Poetry review – TRAVELLERS OF THE NORTH and HARALD IN BYZANTIUM: Edmund Prestwich considers two collections, by Fiona Smith and Kevin Crossley-Holland, that give voice to characters from history

Travellers of the North

Fiona Smith

Arc Publications

ISBN 978-1911469-18-6

40 pp £7

Travellers of the North

Fiona Smith

Arc Publications

ISBN 978-1911469-18-6

40 pp £7

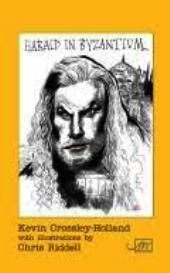

Harald in Byzantium

Kevin Crossley-Holland

with illustrations by Chris Riddell

Arc Publications

ISBN 978-1911469-12-4

40 pp £7

Harald in Byzantium

Kevin Crossley-Holland

with illustrations by Chris Riddell

Arc Publications

ISBN 978-1911469-12-4

40 pp £7

Fiona Smith’s Travellers of the North and Kevin Crossley-Holland’s Harald in Byzantium each consists of a series of poems voicing a character from the past in the first person. In Smith’s book, the character is a more or less legendary refugee travelling to tenth century Norway; in Crossley-Holland’s, an eleventh century Norwegian exiled in Byzantium. So there are broad similarities of content and form. However, their authors approach their material in different spirits. I personally find myself more sympathetic to Crossley-Holland’s approach and found his chapbook the more deeply engaging, but both are well worth reading.

Travellers of the North gave me considerable pleasure. Inspired by the legend of Sunniva, an Irish saint apparently almost forgotten in Ireland itself but revered in Norway, it’s the story of a noblewoman who sailed to Norway to escape a forced marriage. It’s less concerned with presenting Sunniva as a character than with imagining her situation, her primitive voyaging and the strangeness of the seascapes, landscapes and animals she meets. Smith is Irish but moved to Norway and says in her introduction that Sunniva’s story interested her as ‘a tangible link between my country of origin and my adopted home of Norway.’

The taut, muscular energy of her syntax and the vivid physicality of her imagination are obvious from the beginning;

I, Sunniva, am quite mad with longing.

To run wild as a boy in a streel of golden sun,

to run on into the cold drench of dark,

the air sharp with briars, apples, horse sweat.

My father all set jaw, my mother a quiver,

squares her shoulders yet smells of fear.

A number of sections are written in a similarly compressed syntax and with a similar percussive clashing of clustered stressed syllables. Although at this point Sunniva is imagining an escape into a more southern, perhaps Mediterranean world, the very sound of the poem seems to anticipate the harsh northern world she’ll actually find. However, the skill with which Smith suits metre and phonemic texture to subject can be illustrated by quoting a passage in a different style. ‘Sickness’ describes how, while violently seasick in the northern waves, Sunniva feverishly dreams of the Mediterranean she’s moving further and further from:

The silkest of seas takes me down, I slide down,

bisou, bienvenue, bisou, I ease down, blindfolded.

Into a mirage of lavender fields, douce, doucement,

the tarragon, timian, the vines, so lovely, chauteauy

in the brutal shortness of May, on through poplars,

birches, mimosa, to the rocks, scree of the Calanques.

Though a southern harshness breaks through at points, the cadence repeatedly seems to mime a swooning into or in response to the lulling French murmurs of ‘bisou, bienvenue, bisou’ and ‘douce, doucement’. As well as the sheer evocativeness of this, I love its playfulness, as if sympathetically teasing Sunniva for her illusions. I don’t know and can’t find the word ‘chauteauy’, though. I don’t know if it’s a misprint or a piece of Old French or Occitan.

Inevitably, the question of contemporary relevance raises its head in a work of historical fiction. It can be disappointing when works appear to present such relevance in too specific or tendentious a way. What Tolkien says about allegory seems to me to have a bearing on this. In a preface to The Lord of the Rings he wrote, ‘I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations… I much prefer history – true or feigned – with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.’ In her introduction, Smith says ‘these poems are an attempt to liberate Sunniva from her story and give her a voice. Sunniva is reinvented as a sailor, a farmer and an exiled woman in search of a home.’ I find the thirteenth poem, ‘Holy Woman’, shrilly didactic and think Sunniva’s voice is drowned in Smith’s when she says

It seems a woman who lives alone must be a bride of Christ.

If she is not the bride of any other, then she is shackled to him.

Christ will get all glory for what I build here in my own right

which is most galling to me as I have struggled to plough

my own furrow here on Selja

Here, what Smith calls ‘liberating’ Sunniva seems to me to imprison her in a modern argument. There’s no sense that a woman in the tenth century might have seen her situation differently to one in similar circumstances in the twenty-first. I don’t think it’s an accident that the actual writing suddenly gets rather clumsy, especially in the fourth line of this quotation. It seems to me that liberation of Sunniva from hagiographical legend really works when it’s tacit – when we simply see her fleeing forced marriage, then sailing, farming, and searching for a place she can make home. The tale itself is strong enough to carry the author’s idea, without an insistence whose very phrasing seems to yank Sunniva out of the historical context that the rest of the poem has so vividly and concretely created. I would have liked Smith to trust readers to catch for themselves the contemporary resonance of Sunniva’s need and capacity for self-realisation, just as she lets readers feel for themselves how Sunniva’s experiences as a refugee resonate with those of asylum seekers and other displaced persons today. But of course there are readers who like this kind of point made in a more assertive way and will appreciate Smith’s doing so.

..

Forty-odd years ago I was impressed by how vividly Crossley-Holland suggested savage passion in his book The Norse Myths, particularly in ‘Skirnir’s Journey’, which describes the violence of the god Freyr’s love for the ice-cold giant maiden Gerd, and the threats by which his servant Skirnir forces her to accept it. The Harald of Harald in Byzantium is Harald Hardrada, the Norwegian king who attempted to seize the English throne from Harold Godwinson in 1066 and was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, a few weeks before Harold himself was killed at the Battle of Hastings. In his introduction to the book, Crossley-Holland describes him as ‘the greatest warrior of his age’, ‘a man of ferocious energy’, a giant ‘a full hand’s height taller than other men’. Reading these poems I was expecting something in a style like that of Skirnir’s threats. Crossley-Holland gives us something subtler. His Harald may be physically gifted, violent and passionate, but above all he’s intelligent. These poems, spoken when he was the young commander of the Emperor of Byzantium’s Varangian Guard, show him gradually becoming the man who won the throne of Norway and attempted the conquest of both Denmark and England. Because he’s intelligent, it comes naturally to him to reflect on his own life-trajectory. In the first poem, for example, he remembers the ordinariness and innocence of his boyhood:

Forty-odd years ago I was impressed by how vividly Crossley-Holland suggested savage passion in his book The Norse Myths, particularly in ‘Skirnir’s Journey’, which describes the violence of the god Freyr’s love for the ice-cold giant maiden Gerd, and the threats by which his servant Skirnir forces her to accept it. The Harald of Harald in Byzantium is Harald Hardrada, the Norwegian king who attempted to seize the English throne from Harold Godwinson in 1066 and was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, a few weeks before Harold himself was killed at the Battle of Hastings. In his introduction to the book, Crossley-Holland describes him as ‘the greatest warrior of his age’, ‘a man of ferocious energy’, a giant ‘a full hand’s height taller than other men’. Reading these poems I was expecting something in a style like that of Skirnir’s threats. Crossley-Holland gives us something subtler. His Harald may be physically gifted, violent and passionate, but above all he’s intelligent. These poems, spoken when he was the young commander of the Emperor of Byzantium’s Varangian Guard, show him gradually becoming the man who won the throne of Norway and attempted the conquest of both Denmark and England. Because he’s intelligent, it comes naturally to him to reflect on his own life-trajectory. In the first poem, for example, he remembers the ordinariness and innocence of his boyhood:

When I was a boy, I was a boy.

I wrestled with my brothers

and made myself sick on all

the blueberries we picked. I flew kites.

However, at fifteen he was severely wounded in battle and forced into a long exile. As he says, ‘those blades at Stiklestad / cut my childhood out of me.’ Hovering behind ‘When I was a boy I was a boy’ is the famous Biblical declaration, ‘When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.’ Seeing it in this context, I think we more fully appreciate the stylistic choices made in the stark, tautological, fatalistic factualism of Harald’s phrasing in that first line. It’s an expression of the man, in line with the hard clarity we associate with the Icelandic sagas. But Harald’s realism is not that of a man who can only see things in literal terms. He’s a complex, rounded figure, drawn to fantasy, drawn to the voluptuousness of the wealthy south, but uncompromising in his acceptance of the demands reality makes in his dangerous life as travelling war leader. Crossley-Holland’s skill appears in the way he lets different sides to Harald emerge without compromising his portrait of a fundamentally pragmatic and predatory figure. For example, in this poem lyrical feelings glint through Harald’s caustic comparison of Norwegian and Byzantine women and the expression of his resolve to stay longer among the latter, in Miklagard (Byzantium):

The eyes of my women

are dawn-grey, dawn-blue.

Here, they are black stars,

and a little painted fingernail

achieves more than a northern

screech or pitchfork.

In a climate cold and wet

there’s very little blaze,

not even much smoulder.

I have resolved to stay

in Miklagard a little longer.

The fifteenth poem dramatizes this tension still more subtly and economically:

Let the gods grow old.

Let them become mumbling imbeciles.

Let them become incontinent.

Grant me one night

in your apple-garden

forever young,

and I will outgod the gods.

On their own, the last four lines might suggest hyperbolic romantic fervour, like Antony’s ‘Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch / Of the ranged empire fall. The nobleness of life / Is to do thus’ (kissing Cleopatra). However, not just the caustic meanings but the rhythm of the first three lines heavily qualify such sentiments, imposing a clipped, staccato delivery on the concluding four that suggests that whatever he may say, this speaker is not a man who can melt or surrender himself to love.

The subtlety of such imaginative pressures means that strongly as the main lines of Harald’s character are drawn, there’s a kind of shimmering uncertainty, a shifting of shades and tones about the details, so the poems open themselves to different emphases in reading. This makes Harald seem more fully alive, like a real person in a perpetual state of self-discovery and self-making. This person is conceived in historical terms, his character shaped by his world and his particular experiences. Rather than appropriating Harald’s voice, as Smith seems to me to appropriate Sunniva’s in ‘Holy Woman’, Crossley-Holland sets out to imagine how he might really have been and seen himself. A modern perspective comes in through the language he’s given and by the way Crossley-Holland allows humour to play over some of his assertions, for example those about mermaids, which are both deflatingly down to earth in language and spirit –

When I’m king I’ll tether one

in a pool brimming with saltwater

– also a siren.

They can sing together –

while being from a modern point of view absurdly credulous.

Crossley-Holland’s book is illustrated by Chris Riddell’s drawings. Outstanding in themselves, these creatively echo and extend ideas in the text. For example, on the front of the sleeve we have the mature Harald’s fierce, scarred face, twisted mouth and twisted brow drawn in fine black lines made more vivid by touches of pink on lips and lower eyelids and by the coldly ferocious blaze of blue in his eyes. Inside, however, another picture shows him as a baby, a sweetly sleeping little face under the sinister, looming shape of the Norn or Fate who’s drawing out the thread of his destiny. As a physical object, in fact, this chapbook is an exceptionally fine example of collaboration between artists in different media.

Jan 10 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Fiona Smith & Kevin Crossley-Holland

Poetry review – TRAVELLERS OF THE NORTH and HARALD IN BYZANTIUM: Edmund Prestwich considers two collections, by Fiona Smith and Kevin Crossley-Holland, that give voice to characters from history

Fiona Smith’s Travellers of the North and Kevin Crossley-Holland’s Harald in Byzantium each consists of a series of poems voicing a character from the past in the first person. In Smith’s book, the character is a more or less legendary refugee travelling to tenth century Norway; in Crossley-Holland’s, an eleventh century Norwegian exiled in Byzantium. So there are broad similarities of content and form. However, their authors approach their material in different spirits. I personally find myself more sympathetic to Crossley-Holland’s approach and found his chapbook the more deeply engaging, but both are well worth reading.

Travellers of the North gave me considerable pleasure. Inspired by the legend of Sunniva, an Irish saint apparently almost forgotten in Ireland itself but revered in Norway, it’s the story of a noblewoman who sailed to Norway to escape a forced marriage. It’s less concerned with presenting Sunniva as a character than with imagining her situation, her primitive voyaging and the strangeness of the seascapes, landscapes and animals she meets. Smith is Irish but moved to Norway and says in her introduction that Sunniva’s story interested her as ‘a tangible link between my country of origin and my adopted home of Norway.’

The taut, muscular energy of her syntax and the vivid physicality of her imagination are obvious from the beginning;

A number of sections are written in a similarly compressed syntax and with a similar percussive clashing of clustered stressed syllables. Although at this point Sunniva is imagining an escape into a more southern, perhaps Mediterranean world, the very sound of the poem seems to anticipate the harsh northern world she’ll actually find. However, the skill with which Smith suits metre and phonemic texture to subject can be illustrated by quoting a passage in a different style. ‘Sickness’ describes how, while violently seasick in the northern waves, Sunniva feverishly dreams of the Mediterranean she’s moving further and further from:

Though a southern harshness breaks through at points, the cadence repeatedly seems to mime a swooning into or in response to the lulling French murmurs of ‘bisou, bienvenue, bisou’ and ‘douce, doucement’. As well as the sheer evocativeness of this, I love its playfulness, as if sympathetically teasing Sunniva for her illusions. I don’t know and can’t find the word ‘chauteauy’, though. I don’t know if it’s a misprint or a piece of Old French or Occitan.

Inevitably, the question of contemporary relevance raises its head in a work of historical fiction. It can be disappointing when works appear to present such relevance in too specific or tendentious a way. What Tolkien says about allegory seems to me to have a bearing on this. In a preface to The Lord of the Rings he wrote, ‘I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations… I much prefer history – true or feigned – with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.’ In her introduction, Smith says ‘these poems are an attempt to liberate Sunniva from her story and give her a voice. Sunniva is reinvented as a sailor, a farmer and an exiled woman in search of a home.’ I find the thirteenth poem, ‘Holy Woman’, shrilly didactic and think Sunniva’s voice is drowned in Smith’s when she says

Here, what Smith calls ‘liberating’ Sunniva seems to me to imprison her in a modern argument. There’s no sense that a woman in the tenth century might have seen her situation differently to one in similar circumstances in the twenty-first. I don’t think it’s an accident that the actual writing suddenly gets rather clumsy, especially in the fourth line of this quotation. It seems to me that liberation of Sunniva from hagiographical legend really works when it’s tacit – when we simply see her fleeing forced marriage, then sailing, farming, and searching for a place she can make home. The tale itself is strong enough to carry the author’s idea, without an insistence whose very phrasing seems to yank Sunniva out of the historical context that the rest of the poem has so vividly and concretely created. I would have liked Smith to trust readers to catch for themselves the contemporary resonance of Sunniva’s need and capacity for self-realisation, just as she lets readers feel for themselves how Sunniva’s experiences as a refugee resonate with those of asylum seekers and other displaced persons today. But of course there are readers who like this kind of point made in a more assertive way and will appreciate Smith’s doing so.

..

However, at fifteen he was severely wounded in battle and forced into a long exile. As he says, ‘those blades at Stiklestad / cut my childhood out of me.’ Hovering behind ‘When I was a boy I was a boy’ is the famous Biblical declaration, ‘When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.’ Seeing it in this context, I think we more fully appreciate the stylistic choices made in the stark, tautological, fatalistic factualism of Harald’s phrasing in that first line. It’s an expression of the man, in line with the hard clarity we associate with the Icelandic sagas. But Harald’s realism is not that of a man who can only see things in literal terms. He’s a complex, rounded figure, drawn to fantasy, drawn to the voluptuousness of the wealthy south, but uncompromising in his acceptance of the demands reality makes in his dangerous life as travelling war leader. Crossley-Holland’s skill appears in the way he lets different sides to Harald emerge without compromising his portrait of a fundamentally pragmatic and predatory figure. For example, in this poem lyrical feelings glint through Harald’s caustic comparison of Norwegian and Byzantine women and the expression of his resolve to stay longer among the latter, in Miklagard (Byzantium):

The fifteenth poem dramatizes this tension still more subtly and economically:

On their own, the last four lines might suggest hyperbolic romantic fervour, like Antony’s ‘Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch / Of the ranged empire fall. The nobleness of life / Is to do thus’ (kissing Cleopatra). However, not just the caustic meanings but the rhythm of the first three lines heavily qualify such sentiments, imposing a clipped, staccato delivery on the concluding four that suggests that whatever he may say, this speaker is not a man who can melt or surrender himself to love.

The subtlety of such imaginative pressures means that strongly as the main lines of Harald’s character are drawn, there’s a kind of shimmering uncertainty, a shifting of shades and tones about the details, so the poems open themselves to different emphases in reading. This makes Harald seem more fully alive, like a real person in a perpetual state of self-discovery and self-making. This person is conceived in historical terms, his character shaped by his world and his particular experiences. Rather than appropriating Harald’s voice, as Smith seems to me to appropriate Sunniva’s in ‘Holy Woman’, Crossley-Holland sets out to imagine how he might really have been and seen himself. A modern perspective comes in through the language he’s given and by the way Crossley-Holland allows humour to play over some of his assertions, for example those about mermaids, which are both deflatingly down to earth in language and spirit –

while being from a modern point of view absurdly credulous.

Crossley-Holland’s book is illustrated by Chris Riddell’s drawings. Outstanding in themselves, these creatively echo and extend ideas in the text. For example, on the front of the sleeve we have the mature Harald’s fierce, scarred face, twisted mouth and twisted brow drawn in fine black lines made more vivid by touches of pink on lips and lower eyelids and by the coldly ferocious blaze of blue in his eyes. Inside, however, another picture shows him as a baby, a sweetly sleeping little face under the sinister, looming shape of the Norn or Fate who’s drawing out the thread of his destiny. As a physical object, in fact, this chapbook is an exceptionally fine example of collaboration between artists in different media.