Poetry review – BEAUTIFUL MONSTERS: Thomas Ovans examines Stuart Henson’s carefully curated cabinet of curiosities

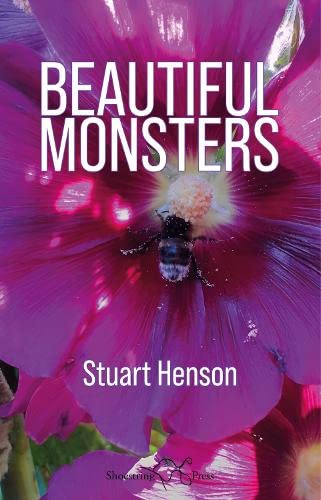

Beautiful Monsters

Stuart Henson

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9781915553164

56 pp £10

Beautiful Monsters

Stuart Henson

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9781915553164

56 pp £10

Stuart Henson’s Beautiful Monsters includes poems about creatures such as bees and bookworms, which seem rather small to be monsters; and it also mentions monstrous acts presided over by some very unbeautiful Roman emperors. On the journey between these extremes we meet St George’s dragon and real life creatures such as bears and elephants which might well seem to be monsters if we encountered them in the wild.

The book’s beginning is small-scale and domestic – a bee trapped behind a window and “struck with its baffling transparency”. This is a fairly easy domestic rescue project, simpler than the spider in the bath or bird in the conservatory. “An A4 sheet to guide him free / and he skies away …” But now comes one of Henson’s wry turns when he says more about the nature of the convenient piece of paper

Good use for your poem: saving a bee.

Think of the hives of them – in drawers,

notebooks, anthologies. Tear them all out!

Their noise, their restlessness, humming incessantly …

This is very much my sort of poem about the natural world: one that starts with imaginative description and then draws our thoughts away to a wider reflection.

Henson also takes a matter of fact view of poetry in its printed form in ‘Bookworm’ where he wonders whether what the creature digests is

… dust at its best or just

jottings of madness

or nothing

but poetry

Notwithstanding the previous two extracts, it should not be thought that Henson is unserious about poetry. The collection gives ample evidence of craft: good word choices and skilful use of rhyme and form. For instance, ‘Tunes for Bears to Dance to’ is an excellent demonstration piece about the effect on the ear of different rhythmic patterns. Thus two-beats-to-the-bar portrays the unhappy animal’s lumbering performance – “Wrong stop. Wrong foot. Wrong turn. Wrong place.” The poem then moves on to a jauntier but equally grim stanza in 3 / 4 time:

The slap of the stick and the kick of the drum.

The drag of the chain and the strain of the song.

The blood on the sawdust. The weight of the light.

The rime on the straw in the frost-eaten night.

It is good to be reminded of the simple power of traditional descriptive story-telling verse forms; and Henson goes on to offer a couple more excellent examples of beats for his bear to dance to.

Another big beast in the contents list turns out, in fact, to be a metaphor. ‘The Elephant that Sits on your Head’ is in fact one of those pachyderms whose presence is very evident but rarely spoken about. This is the British class system with all its pitfalls in the form of “correct” pronunciations or dining conventions which, if you have somehow missed the “proper” schooling, create in you an uncertain state where “You gag on shibboleths. / You check which knife…”

Britishness occurs again in ‘Superstore’ (one of the book’s high spots) which is concerned with the debasement of language that might follow from extravagant claims made about the love – or even “passion” – supposed to have gone into the harvesting, manufacture and packing of products on the shelves. This poem is a sestina and is one of the best examples of the form that I have come across, not least because the six end-words make a very natural appearance on every return so that one is not forced into being aware of the artifice. Here’s the last summing-up stanza:

British or not, I still set store by words like love.

Take care. You have a choice: to keep them fresh

or let them be REDUCED TO CLEAR.

‘Superstore’ makes a serious point but it is also a playful poem. Elsewhere Henson seems out-and-out playful as in ‘L’Après Midi d’un Phone’ which makes us eye-witnesses of an amorous episode:

First thing she did was place it on the glass surface

of the bedside table – maybe just on purpose

to make a point about the other men she’d had.

It did that anyway, vibrating like a mad

hornet at intervals. One time it went off right

at the wrong moment, and it didn’t stop all night.

Notice again the pleasing use of rhyme in this intriguing bit of scene-setting. The poem goes on to include short quotes from the original Mallarmé poem that Henson’s title alludes to; and this borrowing from the French perhaps prefigures the section towards the end of the book where Henson gives his versions of works by Gautier, Baudelaire and Rimbaud. The collective title ‘The Rooftops of Paris’ gives an idea of the ambience he is aiming for. He shows us “a garret / that for the sake of art // is framed exactly by two soil pipes”; he finds “a broad oak cupboard, ancient and mellowed, / aged dark like some nonagenarian”; and out of doors he observes rooks “neutral as undertakers” who “sweep in / from the skies on crepe wings”. These are rich, slow and atmospheric poems: but they occasionally become more animated as when a poet (Rimbaud in this case) stops at an inn and is impressed by the charms of the barmaid

Well, she’d be up for it, no doubt of that!

Look when she brings my sandwich how she pouts,

as if to say I’m yours – and on a plate.

Probably not too many male poets would write lines like that on their own behalf nowadays; but in translation it’s OK I suppose.

Much more acceptable observation is found in ‘Factory Girls Playing Football’. “The lads don’t like it but they’ve commandeered the yard.” And, having done so, the girls go about things in their own way so that “nobody loses in this game: no-one keeps score.” The only one to miss out is Sunitra, six months pregnant, and while she watches

Her daughter – it’s a girl – kicks harder now

as if she’s keen to get outside and breathe fresh air,

take on the unfair world; start playing football.

Just as in the opening poem about the bee Henson moves us on from a sensitive description to a hint at a wider implication.

Henson does on occasion leave an observation to speak for itself and one supposes that ‘The Mad Ambulist of Kentish Town’ simply records the sighting of an unusual individual “flat cap, a paper bag, a covid mask: / that sudden unsettling sense of déjà vu. / You’ve seen this man before …” But the craftsman in Henson won’t quite settle for mere reportage and makes it into a neat, ten-line mirror poem.

The back cover blurb for Beautiful Monsters declares that one of the book’s aims is to be a celebration of all things crazy; and the mad ambulist certainly matches that specification. But for full-on dangerous craziness, it’s hard to beat the excesses of the Roman Empire which Henson touches on in the final few pages where he gives his versions of some Latin poetry. Martial’s casual verbal snapshots of scenes from the Coliseum make uncomfortable reading – for instance “Poor criminal Daedalus, rudderless, beating the air. / Now made a treat for us – and six hungry bears!” The reader is warned there is still worse to come in this closing poem which makes a surprisingly uncomfortable ending to an eclectic collection of well-made poetry that is mostly warm-hearted – at least when the author is speaking in his own voice.

Nov 18 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Stuart Henson

Poetry review – BEAUTIFUL MONSTERS: Thomas Ovans examines Stuart Henson’s carefully curated cabinet of curiosities

Stuart Henson’s Beautiful Monsters includes poems about creatures such as bees and bookworms, which seem rather small to be monsters; and it also mentions monstrous acts presided over by some very unbeautiful Roman emperors. On the journey between these extremes we meet St George’s dragon and real life creatures such as bears and elephants which might well seem to be monsters if we encountered them in the wild.

The book’s beginning is small-scale and domestic – a bee trapped behind a window and “struck with its baffling transparency”. This is a fairly easy domestic rescue project, simpler than the spider in the bath or bird in the conservatory. “An A4 sheet to guide him free / and he skies away …” But now comes one of Henson’s wry turns when he says more about the nature of the convenient piece of paper

This is very much my sort of poem about the natural world: one that starts with imaginative description and then draws our thoughts away to a wider reflection.

Henson also takes a matter of fact view of poetry in its printed form in ‘Bookworm’ where he wonders whether what the creature digests is

Notwithstanding the previous two extracts, it should not be thought that Henson is unserious about poetry. The collection gives ample evidence of craft: good word choices and skilful use of rhyme and form. For instance, ‘Tunes for Bears to Dance to’ is an excellent demonstration piece about the effect on the ear of different rhythmic patterns. Thus two-beats-to-the-bar portrays the unhappy animal’s lumbering performance – “Wrong stop. Wrong foot. Wrong turn. Wrong place.” The poem then moves on to a jauntier but equally grim stanza in 3 / 4 time:

It is good to be reminded of the simple power of traditional descriptive story-telling verse forms; and Henson goes on to offer a couple more excellent examples of beats for his bear to dance to.

Another big beast in the contents list turns out, in fact, to be a metaphor. ‘The Elephant that Sits on your Head’ is in fact one of those pachyderms whose presence is very evident but rarely spoken about. This is the British class system with all its pitfalls in the form of “correct” pronunciations or dining conventions which, if you have somehow missed the “proper” schooling, create in you an uncertain state where “You gag on shibboleths. / You check which knife…”

Britishness occurs again in ‘Superstore’ (one of the book’s high spots) which is concerned with the debasement of language that might follow from extravagant claims made about the love – or even “passion” – supposed to have gone into the harvesting, manufacture and packing of products on the shelves. This poem is a sestina and is one of the best examples of the form that I have come across, not least because the six end-words make a very natural appearance on every return so that one is not forced into being aware of the artifice. Here’s the last summing-up stanza:

‘Superstore’ makes a serious point but it is also a playful poem. Elsewhere Henson seems out-and-out playful as in ‘L’Après Midi d’un Phone’ which makes us eye-witnesses of an amorous episode:

Notice again the pleasing use of rhyme in this intriguing bit of scene-setting. The poem goes on to include short quotes from the original Mallarmé poem that Henson’s title alludes to; and this borrowing from the French perhaps prefigures the section towards the end of the book where Henson gives his versions of works by Gautier, Baudelaire and Rimbaud. The collective title ‘The Rooftops of Paris’ gives an idea of the ambience he is aiming for. He shows us “a garret / that for the sake of art // is framed exactly by two soil pipes”; he finds “a broad oak cupboard, ancient and mellowed, / aged dark like some nonagenarian”; and out of doors he observes rooks “neutral as undertakers” who “sweep in / from the skies on crepe wings”. These are rich, slow and atmospheric poems: but they occasionally become more animated as when a poet (Rimbaud in this case) stops at an inn and is impressed by the charms of the barmaid

Probably not too many male poets would write lines like that on their own behalf nowadays; but in translation it’s OK I suppose.

Much more acceptable observation is found in ‘Factory Girls Playing Football’. “The lads don’t like it but they’ve commandeered the yard.” And, having done so, the girls go about things in their own way so that “nobody loses in this game: no-one keeps score.” The only one to miss out is Sunitra, six months pregnant, and while she watches

Just as in the opening poem about the bee Henson moves us on from a sensitive description to a hint at a wider implication.

Henson does on occasion leave an observation to speak for itself and one supposes that ‘The Mad Ambulist of Kentish Town’ simply records the sighting of an unusual individual “flat cap, a paper bag, a covid mask: / that sudden unsettling sense of déjà vu. / You’ve seen this man before …” But the craftsman in Henson won’t quite settle for mere reportage and makes it into a neat, ten-line mirror poem.

The back cover blurb for Beautiful Monsters declares that one of the book’s aims is to be a celebration of all things crazy; and the mad ambulist certainly matches that specification. But for full-on dangerous craziness, it’s hard to beat the excesses of the Roman Empire which Henson touches on in the final few pages where he gives his versions of some Latin poetry. Martial’s casual verbal snapshots of scenes from the Coliseum make uncomfortable reading – for instance “Poor criminal Daedalus, rudderless, beating the air. / Now made a treat for us – and six hungry bears!” The reader is warned there is still worse to come in this closing poem which makes a surprisingly uncomfortable ending to an eclectic collection of well-made poetry that is mostly warm-hearted – at least when the author is speaking in his own voice.