Poetry review – SHELLING PEAS WITH MY GRANDMOTHER IN THE GORGIOLANDS: James Roderick Burns appreciates the atmospheric detail in an admirable first full collection by Sarah Wimbush

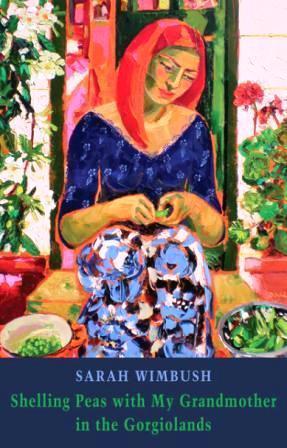

Shelling Peas with My Grandmother in the Gorgiolands

Sarah Wimbush

Bloodaxe Books, 2022

ISBN 978-1-78037-616-5

78 pages, £10.99

Shelling Peas with My Grandmother in the Gorgiolands

Sarah Wimbush

Bloodaxe Books, 2022

ISBN 978-1-78037-616-5

78 pages, £10.99

Shelling Peas is a collection of poetry that works on every page, from the most granular level – an image, a phrase, even a single word – to structured narratives that sustain meaning and atmosphere across multiple pages, and a governing theme that resonates through the whole volume.

At the smallest level, then: in “Pitched early mornin’ at encampment o’Gypsy king Esau Smith”, we see the history of Black Country industrialism in two compressed lines: “Not the circuit of wheat-lined drums … but Black Patch, its slag heaps rolling out / before their wooden wheels like a sea of tar”. A ‘Vixen’ “slides her jaws around a roadkill squirrel”; ‘The Pencil Sharpener’ would “insert a stub, then turn the lever with a whirr / until out came a skin-fresh pencil”.

Each line is crisp, precise and completely right – for mood, setting and effect. Perhaps the greatest single example is Wimbush’s absolutely-not-whimsical depiction of natural foraging (and being foraged), ‘The Hedgehog’s Tale’, whose conclusion blends folk-practice and a clear delight in puncturing over-fine sensibilities, into an unforgettable moment:

spikes wrapped in clay and baked

in a fire pit, sweet

as a chestnut

then ripped

to suck the pith and juice and squeak

As with many of the longer poems, and the book overall, abiding themes are here pressed into each line: the fascinating detail of traditional practices (wild food, clay baking, pit fires); an immediate yoking of comfort and discomfort (sweet / ripped); and a play on the subtle differences between this way of life and others (such as slaughtering the family pig and using everything but the squeal). It is an approach that works, over and again. A poem such as ‘Earring’, for instance, follows its contours on a larger scale, deliberately lingering over the process – and the meaning of details – in a seemingly simple task:

Thread a pin

and push the point

quickly in

and through.

Tie the thread

into a loop

like a ring.

Pull the cotton

now and then

to clear the holes

so the flesh doesn’t grow

on the thread.

From the start (pinching a lobe to numb it) through the end (hanging a thick gold hoop), each stage of the process is described with delicate clarity, a quality the poet often deploys to great effect when describing the grinding hardships of mining, and her family’s industrial heritage. Take ‘William Shaw is lowered down the shaft’, for instance, where

My footing slips, and like a fool

I stretch, reaching out into darkness,

tumbling from the hoppit’s abrupt list

into the belly of a black lagoon.

The descent, loss of light and purchase, the stifling air and “muddy wall, its inexorable cocoon” take a clutch of blunt, inorganic components – the hardware of mining – and figure them in equally challenging organic ways. The water at pit bottom “has its own devices”; the scar of the pit mouth recedes from view and “wanes into a moon”. It is a language, oddly, of dehumanisation by means of nature, exactly the opposite of much literature of industrialism, which seeks to express the indignities of manual labour in brute mechanical terms. Wimbush sustains such ingenuity throughout.

She is at pains in the longer poems to be accurate, as well as inventive, in the details of the travelling life – embracing what is felt, and remembered, real and vital, but never succumbing to any kind of memoirish, teacloth-and-roses lens to obscure hardship or tragedy. In all its stained glory, ‘Our Language’ is “the tune of haulage-boys and shot-firers and Elvis impersonators, their legs smashed to bits at the bottom of shafts and the women who feed everyone’s children”. In the open air, the poet’s grandmother sometimes “only knows slack and air/and her wits”:

No half-dead frills only her histories

and the seasons: the earlies, the hoe, wheat stooks,

mother’s calling basket, wintering-over,

rabbit skins parched to stiff tambours.

In service of a crisp, clear-eyed realism – which celebrates where celebration is due, mourns when necessary, and sometimes sings both feelings at once – Wimbush establishes the boundaries of the collection early; and then with admirable control (but no loss of variety) maintains their shape and import throughout.

It is a magnificent collection, and hard to credit as a debut.

A single poem draws all these strands together with consummate skill, its conclusion a testament to both terse poetic control, thematic consistency and everything in between. ‘Things My Mother Taught Me’ ends with crab – exactly the sort of homely, yet complex, thing which runs through the collection, and typifies Sarah Wimbush’s achievement:

On Doncaster Market you can buy crab in all sorts of ways;

brown paste, arm-and-a-leg white meat, or a hotchpotch of both.

Or from regiments of ceramic croissants with pie-crust edges,

boiled into pink oblivion next to the uncooked; wide-eyed

and numb on their bed of ice. Antennae twitching. Touching.

Males have pointed bellies and by far the larger claws, whereas

the female has broader shoulders, her heart pinned to her chest.

Nov 16 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Sarah Wimbush

Poetry review – SHELLING PEAS WITH MY GRANDMOTHER IN THE GORGIOLANDS: James Roderick Burns appreciates the atmospheric detail in an admirable first full collection by Sarah Wimbush

Shelling Peas is a collection of poetry that works on every page, from the most granular level – an image, a phrase, even a single word – to structured narratives that sustain meaning and atmosphere across multiple pages, and a governing theme that resonates through the whole volume.

At the smallest level, then: in “Pitched early mornin’ at encampment o’Gypsy king Esau Smith”, we see the history of Black Country industrialism in two compressed lines: “Not the circuit of wheat-lined drums … but Black Patch, its slag heaps rolling out / before their wooden wheels like a sea of tar”. A ‘Vixen’ “slides her jaws around a roadkill squirrel”; ‘The Pencil Sharpener’ would “insert a stub, then turn the lever with a whirr / until out came a skin-fresh pencil”.

Each line is crisp, precise and completely right – for mood, setting and effect. Perhaps the greatest single example is Wimbush’s absolutely-not-whimsical depiction of natural foraging (and being foraged), ‘The Hedgehog’s Tale’, whose conclusion blends folk-practice and a clear delight in puncturing over-fine sensibilities, into an unforgettable moment:

As with many of the longer poems, and the book overall, abiding themes are here pressed into each line: the fascinating detail of traditional practices (wild food, clay baking, pit fires); an immediate yoking of comfort and discomfort (sweet / ripped); and a play on the subtle differences between this way of life and others (such as slaughtering the family pig and using everything but the squeal). It is an approach that works, over and again. A poem such as ‘Earring’, for instance, follows its contours on a larger scale, deliberately lingering over the process – and the meaning of details – in a seemingly simple task:

From the start (pinching a lobe to numb it) through the end (hanging a thick gold hoop), each stage of the process is described with delicate clarity, a quality the poet often deploys to great effect when describing the grinding hardships of mining, and her family’s industrial heritage. Take ‘William Shaw is lowered down the shaft’, for instance, where

The descent, loss of light and purchase, the stifling air and “muddy wall, its inexorable cocoon” take a clutch of blunt, inorganic components – the hardware of mining – and figure them in equally challenging organic ways. The water at pit bottom “has its own devices”; the scar of the pit mouth recedes from view and “wanes into a moon”. It is a language, oddly, of dehumanisation by means of nature, exactly the opposite of much literature of industrialism, which seeks to express the indignities of manual labour in brute mechanical terms. Wimbush sustains such ingenuity throughout.

She is at pains in the longer poems to be accurate, as well as inventive, in the details of the travelling life – embracing what is felt, and remembered, real and vital, but never succumbing to any kind of memoirish, teacloth-and-roses lens to obscure hardship or tragedy. In all its stained glory, ‘Our Language’ is “the tune of haulage-boys and shot-firers and Elvis impersonators, their legs smashed to bits at the bottom of shafts and the women who feed everyone’s children”. In the open air, the poet’s grandmother sometimes “only knows slack and air/and her wits”:

In service of a crisp, clear-eyed realism – which celebrates where celebration is due, mourns when necessary, and sometimes sings both feelings at once – Wimbush establishes the boundaries of the collection early; and then with admirable control (but no loss of variety) maintains their shape and import throughout.

It is a magnificent collection, and hard to credit as a debut.

A single poem draws all these strands together with consummate skill, its conclusion a testament to both terse poetic control, thematic consistency and everything in between. ‘Things My Mother Taught Me’ ends with crab – exactly the sort of homely, yet complex, thing which runs through the collection, and typifies Sarah Wimbush’s achievement: