Nov 3 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Hilary Menos

Poetry review – FEAR OF FORKS: Mat Riches finds and enjoys many layers in this short collection by Hilary Menos

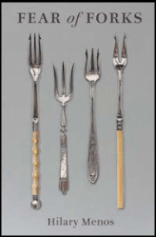

Fear of Forks Hilary Menos Happenstance Press ISBN 9781910131725 £6

Hilary Menos has been quietly building a considerable body of work since winning first prize in the Envoi International Poetry Competition in 2002, and since her 2004 debut pamphlet, Extra Maths (Smith Doorstop).

Menos’s sons have appeared quite in her previous poems and books, most prominently in her immensely powerful pamphlet, Human Tissue (Smith|Doorstop) which deals with the kidney issues that affect her son, Linus, to whom Menos subsequently donated her own kidney. The new pamphlet Fear of Forks contains a shout back to this earlier work in a poem called ‘Living Donor’ and it also features several poems about the poet’s fourth and youngest son Inigo.

It does seem possible to trace a line from that first pamphlet to the present one because, arguably at least, there’s a half-rhyme down the ages. The last poem of Extra Maths ends with “The future goes all ways, like pick-up sticks” while Fear of Forks opens with a poem called ‘Pickle Forks’.

What we don’t see much of in the previous work are references to cutlery. By my rough calculations there are about 4 references to knives across her 2 full collections (Red Devon and Berg) and a couple of nods to a forked tongue and a forked tail in Extra Maths— but that may be pushing the statistics too far… However, what we can see as we read through her body of work to date is a continued sense of protection, of care – both for the world, the environment and for her family.

The poem ‘Pickle Forks’ opens with the line “Today we are going to polish the family silver”. It’s an act of care, of maintenance and of togetherness carried out by various family members that covers a variety of items—both everyday and the special stuff.

Some we use—the cake tongs, the oyster forks, the shovel-shaped caddy spoon, the fancy carver …. Some others, never—cutlery rests, a fish server, Six butter knives with handles of malachite green, the deco coffee spoons, each with its Bakelite bean. And lastly, and most loved, these pickle forks— my four small princes with their spiky crowns and handles off silver, mother-of-pearl and bone.

It might be too obvious to suggest those “most loved” pickle forks are her sons, her “small princes”, but we can put it out there as an idea. Either way, the poem paints a lovely picture of a family life, of time spent together to remove the tarnish of life, and acts as a fine introduction to the Menos cutlery collection.

The next poem, ’Auction’, goes some way to building on the descriptions in ‘Pickle Forks’ and how the poet came across the various items. It starts with “Here I am, again, in these auction rooms / browsing the silverware section for old spoons.” and ends five couplets later with the items she sees “begging me to buy them, no matter how dear, / and tuck them up at home in my cutlery drawer”. Here we see again that sense of caring and looking out for something or someone “no matter how dear”. And this attitude continues into the third poem.

In’ Lifeline’ we see a different side to cutlery, where the poet’s son has cut his thumb with a “whittling knife” and the family has to wait in “Urgences” waiting to find out whether he needs surgery. The family members use a different form of distraction to support one another at this time, an “interactive mobile phone game where Taylor / is stranded on a space station on the moon / and needs our help to find his way back home.”

There is clearly a strong recovery made, as the poems shift later in the book to the same son, now suitably healed and a bit more safety conscious around knives, training to be a chef. The book details his training over the course of several poems. The first of these is ‘Rack, From Left’ and it’s one that deploys a trick that Menos uses a lot to powerful effect: the list. Many of her poems are excellent examples of building (like an excellent chef) layer upon layer of detail. Let’s be clear, it’s not something that is overdone but it is something that features in her work and particularly in Fear of Forks. If we take the a few couplets form the middle as random examples…

the chef’s knife made of local Gresigne oak which he said and revised onto an old knife blank his orange fishing knife why shackle key and spike, the palette knife I’ve used to ice every birthday cake, the ornate Christofle carver bought form Le Bon Coin, the whittling knife which did all that dame to his thumb

Detail upon detail is waiting to be revealed. There’s a son’s determination, a desire to use local materials, a mother’s love being poured into birthday cakes, a sense of thrift (Le Bon Coin is the French equivalent of Gumtree), and a call back to a previous poem. That’s all in the space of six lines and carefully built up. It’s deceptive stuff, but brilliantly done. And all of this before we get to the final pay off in the last line “With these tools to hand / our son is fit for this, and that, and any other world”.

Apart from being given the tools for work and maintenance as an English lad learning in France, there’s a sense of support that sits behind it all as he seeks independence; but what really stands out is the “and that”… You have to wonder what else is going on that required knives? Could it be the potential for the world to be invaded by Zombies? That is certainly present as an option in the book. In the second of three poems referring to zombies, we meet the character of Daryl Dixon from the graphic novels and TV series. In ‘Daryl Dixon In The Vegetable Garden he appears with “his crossbow hooked casually over is shoulder / looking (frankly) rough as fuck”. The poem details a reverie Menos has while gardening where Dixon, the show’s famous loner, is taught to plant vegetables, to find some peace as he works.

We don’t talk much. I ask him about the Zombies once. 'Sometimes people see zombies where there aren’t any,' he says, 'and sometimes people don’t see the zombies at their door because they’ve been there all their lives.' I have no idea what he meant.

You can read this whole poem as an idle fantasy, a flight of fancy, a paean to self-sufficiency (both in terms of existing and mentally); and you could chuck in some existential commentary about the nature of humankind’s tendency towards self-absorption as well. While you can argue The Walking Dead is, at the time of writing, limping towards a conclusion, the same cannot be said of Menos. She’s only getting stronger as time goes by.

So much of the training Menos’ son receives is about selecting the right tool for the right job. We’ve already seen the tools in ‘Rack, From Left’, but elsewhere in a poem like ‘Mis En Place’ we can see her poetic fastidiousness being mirrored in her son’s work. He’s been learning how to be a waiter, how to lay a table with absolute precision.

After a year on the Bac Pro Cuisine he is au fait with the mise en place, blasé with a baton, each polished knife, fork, spoon nudged by a knuckle to an inch from the table edge, glasses for water, white wine, red, triangulated, salt cellar facing the kitchen.

So far, so good, but the poem takes a powerful turn, by comparing his new skills to those of the young waiters, “Italian, French, Spanish, Swiss— / who landed a job with Cunard’s White Star Line”. It describes the conditions they worked in, the lives they made for themselves as they attempted to cope “until the night when everything slid” and all the spoons, knives, forks, etc “were sucked into the depths / spangling like silver fish all the way down.” This scene is especially powerful in light of the poem that precedes it. ‘White Star Line’ is another example of her ability to take what is essentially a list, but layer details in. The poem itemises the cutlery carried on board Titanic, but the final item on the list is offered as a brutal juxtaposition about priorities, hubris and sheer stupidity. I won’t include it here to avoid spoiling the effect, but you can probably work it out.

As I said at the beginning, Hilary Menos has been quietly building a strong body of work in pamphlet form since her last collection. It’s high time we had a new collection, but in the meantime, Fear of Forks will see us through. Now, where’s my Brasso?

Zombie Apocalypse | Wear The Fox Hat

29/10/2023 @ 21:17

[…] up, and allowed me to then be ready for Human Tissue and then Fear of Forks (reviewed by some goon here.It’s been 10 years now since Hilary’s last full collection and a new one really should be […]