Poetry review – SING ME DOWN FROM THE DARK: Sue Wallace-Shaddad reviews Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana’s poetic exploration of cross-cultural relationships

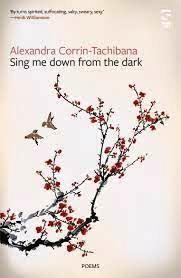

Sing me down from the dark

Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana

Salt Publishing

ISBN 978-1-78463-276-2

http://www.saltpublishing.com

66pp £10.99

Sing me down from the dark

Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana

Salt Publishing

ISBN 978-1-78463-276-2

http://www.saltpublishing.com

66pp £10.99

The opening poem of this collection, ‘Coming Home’, immediately evokes Japan with its use of Japanese words. Ironically Japan is no longer home and the poem title refers to being back in the UK. While readers might know the words ‘sushi’ and ‘miso’, they are less likely to know ‘futsukayoi’ (second day drunkenness). The abundant use of Japanese terms and sometimes script must have presented some proof-reading challenges but they serve to anchor this exploration of relationships in a mainly cross-cultural context.

The collection is organised in six parts. In the first short section, comprising four poems, the narrator is in the UK at Sainsbury’s and then with her young son at The Co-op and at a fishmonger’s. In the prose poem ‘Single Mum, in a Japanese Office, near St Paul’s’, the reader learns about the father that ‘it will be 3 years until he can save enough to live with us’ and the son ‘knows little of Japan’. There is pathos in the final lines of ‘Photos’: ‘Yes, my stranger husband. Once, we were a fit’. So, at this point, the poet has set up the reader to expect a reckoning of a long-distance relationship with all that entails.

A feature of this collection is the way it deals with relationships via the lens of the everyday, whether life at home, shopping, trips or meals. This makes the poems very relatable. The next section charts the early days of getting to know one another and then marriage. ‘A Personal Glossary’, formed of couplets, lists Japanese words with definitions of meaning which have a particular resonance for the poet:

enka: a sentimental karaoke song

and form of seduction

Karaoke is a thread running through this section. In ‘Bride Face’

They loved me

in ivory and tiara,

singing karaoke.

The poem ‘Sensei’ explores the feeling of difference when new to a country and its culture. These three lines subtly suggest this:

Yutaka leaves, and I stare

at my size eight feet,

on square-matted tatami.

In the prose poem ‘Japanese Bathing Etiquette’, we are introduced to the term ‘gaijin’ which features in several poems (a footnote explains this as ‘foreigner, outside person’). The poet writes she has ‘broken bathing rules’ […] because of the tiny snake tattoo, on my left buttock’. She is even ‘gaijin of the week’ in ‘Portrait of a Gaijin’ which recounts the fact that her portrait will ‘be displayed/ in Shizuoka City Library.’

There is real poignancy in many poems. ‘Heart of a Japanese’ reflects on the in-laws who will be affected by the plan to divorce. The soon to be ex-husband comforts his mother – he will

Soothe her with jokes. I watch her stroke-ravaged

face crumple, to cry, into her donburi rice bowl.

Another poignant poem later in the collection is ‘The Japanese Gardener’ which starts

Since she told him she doesn’t love

him, he’s taken up gardening,

he’s planting her birth flower, a pink rose,

for happiness. […]

The poems go back and forth in time in this collection which I found a bit confusing. I was not always sure which relationship (including two international marriages as mentioned on the back cover) was in focus. In the third section, the poet goes back to ‘Our twenty-something selves’ in ‘The Road to Ippon Matsu’ where she is ‘aka no tanin – a red stranger’. The prose poem ‘Red Strangers’ takes up the theme of first meeting again, contrasting the couple’s places of origin, Shizuoka-Shi and Bradford-on-Avon.

The poem ‘My Darling is a Foreigner’ raises issues of not following cultural expectations: ‘she does not rinse sticky rice before cooking’. Here, the repetition inherent in the pantoum form is effective as a drumbeat for what one half of the couple may see as a failing. Such issues also feature in ‘Cross-Cultural Communication in the Home Place’. The reader can sense discomfort in the lines:

And the need to push

our son’s head down

to teach him

to bow

before he can talk

The breakdown of a relationship with all the associated rawness is captured in the fourth section. In ‘Ghazal for my husband, on International Woman’s Day’ (a somewhat ironic title given the circumstances), the poet lists observations by the husband:

How’s your hobby going? you ask, close up and in my way.

We never had any problems until this poetry thing. Am I annoying you darling? you say.

In ‘Masks’, there is clearly another bone of contention (which is bound to strike a chord with many readers): ‘/ Reload the dishwasher / in a more efficient way.’ The clipped short phrases in this prose poem, broken by slashes, reinforce the feeling of disconnect in a relationship where ‘Our countries have a 9-hour difference’. Corrin-Tachibana also offers a sequence of prose poems in two columns over three pages, ‘Unpacking our relationship’, covering a relationship from the outset in ‘Love Bombing’ to its end in ‘Gaslighting’. The short lines in ‘Narcissistic Personality Disorder’ with their compression of emotion are very telling:

And

what of my modest poetry

prize? I can donate it to our

domestic account, you tell

our son. You will pay in less

this month.

The collection’s two final sections consist of poems about a new relationship with ‘G’ (to whom the collection is dedicated). The focus of the poems now shifts to meetings on Zoom, in Scotland and Spain. Instead of Japanese vocabulary, the reader meets Spanish words: ‘castellana pots’ and ‘patatas bravas’ in ‘When I WhatsApp you in San Lorenzo de El Escorial’ and ‘caramel torrijas’ in ‘Writing Guadalupe’.

In these poems, Corrin-Tachibana charts the emotional path of two individuals together but also with a hinterland of former partners. In ‘Bickerton’s Way’, the couple go back to their accommodation

knowing that tomorrow we must

leave for separate homes

and wrestle with the noise.

In the prose poem ‘Her’ the narrator addresses her partner, imagining the relationship he has had with his estranged wife:

Say you don’t think of seeing her in the coffee shop

in Bangor 34 years ago. Say you didn’t have nick-

names.

‘Home’ is a lovely poem of longing for a relationship to feel like home:

[…] Where we no longer

suffer skin hunger. A place

where boundaries, boundaries

of us begin to blur: […]

The poet does not hold back in Sing me down from the dark. This collection is testimony to a full emotional life, with poems which are both singular and universal in meaning.

Nov 29 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana

Poetry review – SING ME DOWN FROM THE DARK: Sue Wallace-Shaddad reviews Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana’s poetic exploration of cross-cultural relationships

The opening poem of this collection, ‘Coming Home’, immediately evokes Japan with its use of Japanese words. Ironically Japan is no longer home and the poem title refers to being back in the UK. While readers might know the words ‘sushi’ and ‘miso’, they are less likely to know ‘futsukayoi’ (second day drunkenness). The abundant use of Japanese terms and sometimes script must have presented some proof-reading challenges but they serve to anchor this exploration of relationships in a mainly cross-cultural context.

The collection is organised in six parts. In the first short section, comprising four poems, the narrator is in the UK at Sainsbury’s and then with her young son at The Co-op and at a fishmonger’s. In the prose poem ‘Single Mum, in a Japanese Office, near St Paul’s’, the reader learns about the father that ‘it will be 3 years until he can save enough to live with us’ and the son ‘knows little of Japan’. There is pathos in the final lines of ‘Photos’: ‘Yes, my stranger husband. Once, we were a fit’. So, at this point, the poet has set up the reader to expect a reckoning of a long-distance relationship with all that entails.

A feature of this collection is the way it deals with relationships via the lens of the everyday, whether life at home, shopping, trips or meals. This makes the poems very relatable. The next section charts the early days of getting to know one another and then marriage. ‘A Personal Glossary’, formed of couplets, lists Japanese words with definitions of meaning which have a particular resonance for the poet:

Karaoke is a thread running through this section. In ‘Bride Face’

The poem ‘Sensei’ explores the feeling of difference when new to a country and its culture. These three lines subtly suggest this:

In the prose poem ‘Japanese Bathing Etiquette’, we are introduced to the term ‘gaijin’ which features in several poems (a footnote explains this as ‘foreigner, outside person’). The poet writes she has ‘broken bathing rules’ […] because of the tiny snake tattoo, on my left buttock’. She is even ‘gaijin of the week’ in ‘Portrait of a Gaijin’ which recounts the fact that her portrait will ‘be displayed/ in Shizuoka City Library.’

There is real poignancy in many poems. ‘Heart of a Japanese’ reflects on the in-laws who will be affected by the plan to divorce. The soon to be ex-husband comforts his mother – he will

Another poignant poem later in the collection is ‘The Japanese Gardener’ which starts

The poems go back and forth in time in this collection which I found a bit confusing. I was not always sure which relationship (including two international marriages as mentioned on the back cover) was in focus. In the third section, the poet goes back to ‘Our twenty-something selves’ in ‘The Road to Ippon Matsu’ where she is ‘aka no tanin – a red stranger’. The prose poem ‘Red Strangers’ takes up the theme of first meeting again, contrasting the couple’s places of origin, Shizuoka-Shi and Bradford-on-Avon.

The poem ‘My Darling is a Foreigner’ raises issues of not following cultural expectations: ‘she does not rinse sticky rice before cooking’. Here, the repetition inherent in the pantoum form is effective as a drumbeat for what one half of the couple may see as a failing. Such issues also feature in ‘Cross-Cultural Communication in the Home Place’. The reader can sense discomfort in the lines:

The breakdown of a relationship with all the associated rawness is captured in the fourth section. In ‘Ghazal for my husband, on International Woman’s Day’ (a somewhat ironic title given the circumstances), the poet lists observations by the husband:

In ‘Masks’, there is clearly another bone of contention (which is bound to strike a chord with many readers): ‘/ Reload the dishwasher / in a more efficient way.’ The clipped short phrases in this prose poem, broken by slashes, reinforce the feeling of disconnect in a relationship where ‘Our countries have a 9-hour difference’. Corrin-Tachibana also offers a sequence of prose poems in two columns over three pages, ‘Unpacking our relationship’, covering a relationship from the outset in ‘Love Bombing’ to its end in ‘Gaslighting’. The short lines in ‘Narcissistic Personality Disorder’ with their compression of emotion are very telling:

And what of my modest poetry prize? I can donate it to our domestic account, you tell our son. You will pay in less this month.The collection’s two final sections consist of poems about a new relationship with ‘G’ (to whom the collection is dedicated). The focus of the poems now shifts to meetings on Zoom, in Scotland and Spain. Instead of Japanese vocabulary, the reader meets Spanish words: ‘castellana pots’ and ‘patatas bravas’ in ‘When I WhatsApp you in San Lorenzo de El Escorial’ and ‘caramel torrijas’ in ‘Writing Guadalupe’.

In these poems, Corrin-Tachibana charts the emotional path of two individuals together but also with a hinterland of former partners. In ‘Bickerton’s Way’, the couple go back to their accommodation

In the prose poem ‘Her’ the narrator addresses her partner, imagining the relationship he has had with his estranged wife:

‘Home’ is a lovely poem of longing for a relationship to feel like home:

The poet does not hold back in Sing me down from the dark. This collection is testimony to a full emotional life, with poems which are both singular and universal in meaning.