THIS RARE SPIRIT: Kevin Saving shares some thoughts on the life of poet Charlotte Mew as set out in a recent biography by Julia Copus

This Rare Spirit

A Life of Charlotte Mew

Julia Copus

Faber & Faber

ISBN 978-0-571-31354-9

464pp £10.99

This Rare Spirit

A Life of Charlotte Mew

Julia Copus

Faber & Faber

ISBN 978-0-571-31354-9

464pp £10.99

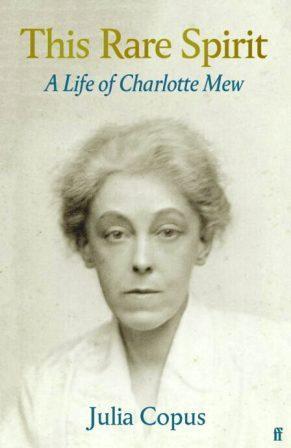

Very little out of the ordinary appears to have happened in the life of Charlotte Mary Mew (‘Lotti’ to her family) and, whilst this may be problematic for the biographer – and reader – it might well have been her salvation as a writer. Even the few photographs which survive are somehow ‘bleached’ of colour. Hers was an existence of shabby-genteel, middle-class (relative) indigence – we have to remember that she and her long-lived mother almost always contrived to retain a Maid – and the few, admittedly traumatic, events in it came close to breaking her.

Born in 1869, daughter and grand-daughter of architects, Lotti was one of seven siblings, three of whom died young – with two others experiencing long-term institutionalisation in asylums for the insane. Charlotte never took a job, seems never to have had a love affair and spent much of her time looking after her possessive, class-conscious mother in Bloomsbury, London. in this last task she was aided – in addition to those Maids – by her one true intimate, her slightly younger artist-sister, ‘Anne’.

Mew’s writing, although it eventually attracted contemporary admirers such as Hardy, Masefield and de la Mare, can be uneven. Her one undoubted tour de force, the dramatic monologue ‘The Farmer’s Bride’, is a brilliant piece of imaginative ventriloquism, haunting in its depiction of a spurious, quasi-coercive marriage as recounted by the puzzled, lovelorn husband and which is sensitively even-handed in its treatment of both marital victims. Elsewhere, she can write compellingly of her equivocal relationships with a God whose ‘arms are full of broken things’ or a physicality which asserts ‘we are what we are: the spirit afterwards, but first the touch’. She had an ambivalent, very un-modern attitude to her writing career, eschewing self-promotion, detesting any attempts at lionization or patronization, consistently refusing to be regarded as belonging to any particular ‘school’ or – ever – of being anyone’s ‘pet’.

Most deaths have at least some sordid element and Mew’s was no different. The two drawn-out terminal illnesses (within four years of each other) of first her mother and then (to cancer) of Anne, affected her deeply. She secreted a bottle of Lysol disinfectant into the nursing home to which she had been admitted (with ‘Depression’) and although she was discovered quite quickly and a doctor summoned, the corrosive effects of ingestion were always going to prove fatal. Her (reported) last words “Don’t keep me, let me go” bear a strange echo with the farmer’s bride’s “Not near, not near!” Copus helpfully informs us that this form of suicide was once quite common, there having been 361 recorded instances of self-poisoning by Lysol in Britain during the previous year (1927).

Julia Copus, herself an award-winning poet (and the originator of the ‘Specular’ verse-form) has, with This Rare Spirit, furnished us with a biography which is well-researched, compassionate and insightful. Whilst it is not, exactly, a ‘page-turner’, there are mitigating factors. Charlotte Mew’s was a life sketched out on a small canvas (physically tiny, she was said to stand only four foot, ten inches tall). If she was lacking in what Americans call ‘Chutzpah’ and, perhaps, a little in sheer creative energy, she did manage to write one enduring artistic masterpiece. And how many of us can truthfully say that?

Oct 2 2022

THIS RARE SPIRIT

THIS RARE SPIRIT: Kevin Saving shares some thoughts on the life of poet Charlotte Mew as set out in a recent biography by Julia Copus

Very little out of the ordinary appears to have happened in the life of Charlotte Mary Mew (‘Lotti’ to her family) and, whilst this may be problematic for the biographer – and reader – it might well have been her salvation as a writer. Even the few photographs which survive are somehow ‘bleached’ of colour. Hers was an existence of shabby-genteel, middle-class (relative) indigence – we have to remember that she and her long-lived mother almost always contrived to retain a Maid – and the few, admittedly traumatic, events in it came close to breaking her.

Born in 1869, daughter and grand-daughter of architects, Lotti was one of seven siblings, three of whom died young – with two others experiencing long-term institutionalisation in asylums for the insane. Charlotte never took a job, seems never to have had a love affair and spent much of her time looking after her possessive, class-conscious mother in Bloomsbury, London. in this last task she was aided – in addition to those Maids – by her one true intimate, her slightly younger artist-sister, ‘Anne’.

Mew’s writing, although it eventually attracted contemporary admirers such as Hardy, Masefield and de la Mare, can be uneven. Her one undoubted tour de force, the dramatic monologue ‘The Farmer’s Bride’, is a brilliant piece of imaginative ventriloquism, haunting in its depiction of a spurious, quasi-coercive marriage as recounted by the puzzled, lovelorn husband and which is sensitively even-handed in its treatment of both marital victims. Elsewhere, she can write compellingly of her equivocal relationships with a God whose ‘arms are full of broken things’ or a physicality which asserts ‘we are what we are: the spirit afterwards, but first the touch’. She had an ambivalent, very un-modern attitude to her writing career, eschewing self-promotion, detesting any attempts at lionization or patronization, consistently refusing to be regarded as belonging to any particular ‘school’ or – ever – of being anyone’s ‘pet’.

Most deaths have at least some sordid element and Mew’s was no different. The two drawn-out terminal illnesses (within four years of each other) of first her mother and then (to cancer) of Anne, affected her deeply. She secreted a bottle of Lysol disinfectant into the nursing home to which she had been admitted (with ‘Depression’) and although she was discovered quite quickly and a doctor summoned, the corrosive effects of ingestion were always going to prove fatal. Her (reported) last words “Don’t keep me, let me go” bear a strange echo with the farmer’s bride’s “Not near, not near!” Copus helpfully informs us that this form of suicide was once quite common, there having been 361 recorded instances of self-poisoning by Lysol in Britain during the previous year (1927).

Julia Copus, herself an award-winning poet (and the originator of the ‘Specular’ verse-form) has, with This Rare Spirit, furnished us with a biography which is well-researched, compassionate and insightful. Whilst it is not, exactly, a ‘page-turner’, there are mitigating factors. Charlotte Mew’s was a life sketched out on a small canvas (physically tiny, she was said to stand only four foot, ten inches tall). If she was lacking in what Americans call ‘Chutzpah’ and, perhaps, a little in sheer creative energy, she did manage to write one enduring artistic masterpiece. And how many of us can truthfully say that?