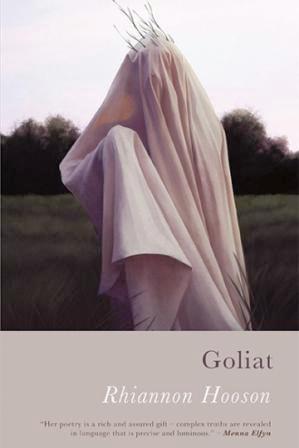

Poetry review – GOLIAT: Pat Edwards is captivated by Rhiannon Hooson’s new collection

Goliat

Rhiannon Hooson

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-656-3

£9.99

Goliat

Rhiannon Hooson

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-656-3

£9.99

The opening poems in this fine and deeply engaging collection ooze imagination and take the reader into an absorbing world of fantasy, dreams and sometimes even nightmares. Hooson can conjure up nights with Frida Kahlo telling us, ‘I loved you only in the garden / women go to when they sleep’ and setting the pulse racing. This is quickly followed by her musings on a work of art entitled Stag Boy by Welshman Clive Hicks-Jenkins, in which ‘It does not seem to matter when he lies, / or when he tells the truth’. We know by now that nothing is fixed, everything is fluid and we must expect the unexpected – for instance a trip across Europe with a fictional warrior woman from Game of Thrones with whom we sneak kisses ‘in the shadow / of a drab billboard before a wooded hill’ in Genoa.

But it is not all love affairs and soon the dreadful shadow of illness, real and imagined, looms. There are nurses in attendance, whose hands we can squeeze ‘if anything hurts’, and we have to face the horror of a neurological condition, Bell’s Palsy. Perhaps we will require a leech, ‘the only thing that knows blood as well as a woman’, or we will encounter Typhoid Mary for ‘those who deserved sickness.’ And even if we don’t fall ill, we might encounter war or stumble upon places where ‘you and I are ghosts in future’s forest’ or, worse still, where life is engineered, digitised, a place deprived of light, ‘an event horizon’.

Perhaps it was inevitable then that the collection would bring us to the nightmare that is the climate crisis. Hooson takes a calculated risk with poems about the natural world, never preaching but gently laying bare some harsh facts. She reminds us, using rich and beautiful language, that the earth has been here forever and we are merely passing through doing untold damage. In “Doggerland”, the focus is on the endangered White Fronted Goose. Hooson’s choice of words around the notion of a landscape’s grip, a creature’s survival and the connotation of rope and fastenings is so subtle. Even the double meaning of the word ‘knot’ is carefully exploited,

Ice loosens its knots

in the rope of the water

and you

- a knot in the rope

of the air –

unravel:

The shadow of a wing

on the rind of the water

and then nothing.

There follows a series of sensuous poems, on the face of it exploring dyes and weaving but maybe so much more, as if to return us to a more simple existence and focus:

We delve in the deep earth,

bring pigments to grind, rub our palms together until,

like insects punctuating a summer night,

our bodies become a song.

These are just gorgeous poems, intimate and as colourful as the dyes themselves. Hooson gently reminds us,

Time sags

like stretched elastic. There is so much

to be perceived

and so little time left.

From here the poems take us to autumnal orchards, November, walking through cities, and winter with its ‘palette of greys’. Hooson gives us eleven poems on the theme of a female artist named Aubrey. But who is this painter who studies strange, ritualistic scenes depicting women young and old; who frames seaside images alongside burning pyres and torches? The hint is in the acknowledgements at the back of the book, where we learn that the poems “Full Moon on Fish Street” are in fact devised using pages from Virginia Woolf’s great novels The Waves and To The Lighthouse. Once again Hooson is unflinching in her bold imaginings and makes credible the possibility that such an artist might exist. Each of the poems has yearning, a piercing atmospheric and the quiver of the sea.

If ever there was a way of plunging us back into grim reality, Hooson’s poem “Southiou” about the death of the young, up and coming photographic artist Khadija Saye in the Grenfell Tower fire is it. Hooson masters all her tools to depict ‘the heat and smell of nitrate’ in this emotional and devastating piece.

Hooson finishes the collection with further poems prompted by works of art, and others with an environmental vibe. It is clear that she revels in the feelings evoked by art, and that she is skilful in finding fresh ways to be inspired and to take unexpected paths in crafting her poems. Amongst these closing poems is hidden a little gem, “The Silent Game”, in which Hooson reveals the monthly ritual played out in an American school, to practise the drill in case a gunman should break in. She tells us that the children ‘are young / and brave and the world / owes them anything, everything.’ Really, the whole collection is a masterclass in poetic language and form; it represents carefully researched themes and the employment of inventive devices to create a truly magical, luminous book.

Oct 13 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Rhiannon Hooson

Poetry review – GOLIAT: Pat Edwards is captivated by Rhiannon Hooson’s new collection

The opening poems in this fine and deeply engaging collection ooze imagination and take the reader into an absorbing world of fantasy, dreams and sometimes even nightmares. Hooson can conjure up nights with Frida Kahlo telling us, ‘I loved you only in the garden / women go to when they sleep’ and setting the pulse racing. This is quickly followed by her musings on a work of art entitled Stag Boy by Welshman Clive Hicks-Jenkins, in which ‘It does not seem to matter when he lies, / or when he tells the truth’. We know by now that nothing is fixed, everything is fluid and we must expect the unexpected – for instance a trip across Europe with a fictional warrior woman from Game of Thrones with whom we sneak kisses ‘in the shadow / of a drab billboard before a wooded hill’ in Genoa.

But it is not all love affairs and soon the dreadful shadow of illness, real and imagined, looms. There are nurses in attendance, whose hands we can squeeze ‘if anything hurts’, and we have to face the horror of a neurological condition, Bell’s Palsy. Perhaps we will require a leech, ‘the only thing that knows blood as well as a woman’, or we will encounter Typhoid Mary for ‘those who deserved sickness.’ And even if we don’t fall ill, we might encounter war or stumble upon places where ‘you and I are ghosts in future’s forest’ or, worse still, where life is engineered, digitised, a place deprived of light, ‘an event horizon’.

Perhaps it was inevitable then that the collection would bring us to the nightmare that is the climate crisis. Hooson takes a calculated risk with poems about the natural world, never preaching but gently laying bare some harsh facts. She reminds us, using rich and beautiful language, that the earth has been here forever and we are merely passing through doing untold damage. In “Doggerland”, the focus is on the endangered White Fronted Goose. Hooson’s choice of words around the notion of a landscape’s grip, a creature’s survival and the connotation of rope and fastenings is so subtle. Even the double meaning of the word ‘knot’ is carefully exploited,

There follows a series of sensuous poems, on the face of it exploring dyes and weaving but maybe so much more, as if to return us to a more simple existence and focus:

These are just gorgeous poems, intimate and as colourful as the dyes themselves. Hooson gently reminds us,

From here the poems take us to autumnal orchards, November, walking through cities, and winter with its ‘palette of greys’. Hooson gives us eleven poems on the theme of a female artist named Aubrey. But who is this painter who studies strange, ritualistic scenes depicting women young and old; who frames seaside images alongside burning pyres and torches? The hint is in the acknowledgements at the back of the book, where we learn that the poems “Full Moon on Fish Street” are in fact devised using pages from Virginia Woolf’s great novels The Waves and To The Lighthouse. Once again Hooson is unflinching in her bold imaginings and makes credible the possibility that such an artist might exist. Each of the poems has yearning, a piercing atmospheric and the quiver of the sea.

If ever there was a way of plunging us back into grim reality, Hooson’s poem “Southiou” about the death of the young, up and coming photographic artist Khadija Saye in the Grenfell Tower fire is it. Hooson masters all her tools to depict ‘the heat and smell of nitrate’ in this emotional and devastating piece.

Hooson finishes the collection with further poems prompted by works of art, and others with an environmental vibe. It is clear that she revels in the feelings evoked by art, and that she is skilful in finding fresh ways to be inspired and to take unexpected paths in crafting her poems. Amongst these closing poems is hidden a little gem, “The Silent Game”, in which Hooson reveals the monthly ritual played out in an American school, to practise the drill in case a gunman should break in. She tells us that the children ‘are young / and brave and the world / owes them anything, everything.’ Really, the whole collection is a masterclass in poetic language and form; it represents carefully researched themes and the employment of inventive devices to create a truly magical, luminous book.