Poetry review – FEELING UNUSUAL: John Forth gets to grips with Ann Drysdale‘s vivid imagery and imagination

Feeling Unusual

Ann Drysdale

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9 7871912 524983

58pp £10.00

Feeling Unusual

Ann Drysdale

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9 7871912 524983

58pp £10.00

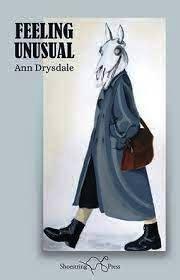

With an impressive Mari Lwyd striding across the cover (painted by Allison Neal) Ann Drysdale’s latest collection introduces an ‘imaginary friend’ who sometimes sounds like a poet. Ann Drysdale is not widely known for ‘wassailing’ and this particular hobby-horse translates either as ‘blessed Mary’ or ‘grey mare’, but the point of the device, traditionally, is to request entry for the price of a song around Christmas time or the Winter Solstice. So be it. A bit of fun and potentially a teasing metaphor:

But the dance is fast and the road is long

and sometimes I need to catch my breath

so I stop at your door and I sing my song

of the old illusions of life and death.

I’ll sing it for you and then I’ll knock:

Here I am, O my next of kin –

and you will turn the key in the lock

to keep me out or bring me in.

(“Mari Lwyd Dances”)

After this ghostly opening, the second poem “Setting Off” is more down-to-earth and spoken by the rider:

Pointed towards outdoors and set to go,

I cock my leg stiffly over the saddle

and settle my behind roughly amidships.

She’s now on a bike (there are pedals) but manages ‘a non-existent trot’; expects to ‘pass unseen’ but everything remains precarious:

Having no brakes, I fly on through the brambles

where nature’s creatures go about their business.

If I had wheels, I’d crash into the wall.

Next, Mari becomes a vehicle for observing the growth of a poet:

I will knock on her door till she remembers

that she was once the Little Grey Pony,

whispering stories of her own adventures

into the busy silence of her head.

(“Mari Lwyd Calls on a Kindred Spirit”)

The third person host occasionally transformed herself into Mari when she would ‘make a wild mane of her cropped hair / to toss in time to her private whinnying’. By the time we reach the fourth Mari poem it is becoming clear that her dozen or so appearances will provide a skeletal framework for the book as a whole. In “Mari Lwyd Finds the Forgotten Horses” she is operating in a kind of limbo of ‘aborted horses in their various stages of completion’ though they never quite ran. They were ‘dreamed up and discarded’ but are nevertheless accessible to the Mari Lwyd:

They were the doors out of the ordinary

by way of books and toys and television.

Saddled with need and bridled with anxiety

they carried nervous passengers through puberty.

...Only the Mari Lwyd knows they’re there.

This is perhaps the most mysterious of the Mari Lwyd poems, veering between a child’s dream of horses and discarded or unfinished poems. I’m not sure the ambiguity is a productive one. “Mari Lwyd Mends the Horses of Matholych”, shown in English and in Welsh, is a raid on the bloody tale of Branwen from the second branch of the Mabinogi. In the story the ruined horses are brought back to life by the use of a magic cauldron. So nothing is lost, nothing wasted. There follows a poem about ‘the postal palaver’ of a mini-mari sent to her (by ‘Nige’) in the post, delayed because it was a small parcel and not a large letter! Here, Mari has to come to terms with modern red tape which might be the reason for ‘her long face’. She’s now become an opportunity to tell an old joke.

Indeed Mari’s contemporary existence goes way beyond the original ‘skull on a broomstick / bobbing above a man clad in a sack’ – or what Sheenagh Pugh (via Mariott Edgar) calls ‘a stick with an ‘orse’s ‘ead ‘andle’. She has now become ‘a bedecked, bejewelled artifact / lit from within (“Mari Lwyd with Bells and Whistles”). The speaker generously concludes that ‘enthusiasm justifies the theft’. Before Mari takes her final curtain she will make an appearance as a kind of grim reaper, the host dispensing with her customary skills to pull out the cloth from under some gathered fine bone china to provide ‘a long crash of desolation’ (“Mari Lwyd Will Be Coming Soon”). They are still together for the poem “Seat” in which ‘She has grown old / little by little in my company’ and in “Badge of Honour” – now become a walking stick with ‘a jolly knob’ stuck on the end:

I turn the stick around, drop it on the floor

so that it bounces back into my hand,

twirl it full circle. Ha! Ba-doom Tish…

She awards herself ‘the Order of the Staircase’ (viz L’esprit de L’escalier) for ‘thinking of a thing I should have said / moments after the moment when I didn’t’. Always the grand idea is paired with a debunking that keeps self-parody in the frame. Similarly, in “The Gravedigger Digs the Difference” she calls upon Hamlet to bolster a claim that the tools of working men (her own tools) are straightforward to those who use them:

The hawk and handsaw of the working class

Are simply left and right – elbow and arse.

Both sequence and book end with a pantomime performance (“Mari Lwyd Meets Marie Lloyd”) – a prose poem in which all of these steps are retraced before an invisible audience: ‘I don’t know who you are, but one look at those teeth tells me we must be related’. For the Curtain Call, ‘Marie is bareheaded, grey-haired and walking with a stick. Mari is now wearing Marie’s hat. They are both transformed’.

*

It is typical of Ann Drysdale that, in this her eighth collection, a liberating sense of humour accompanies dark foreboding pieces about ordinary stuff. It’s as if we’re invited into a mythical, other-worldly place in order to foreground what’s actually going on in the day-to-day of covid isolation, intermittent loneliness and loss. The back cover tells us she once lived on a narrow boat, but here, in “Boat”, she could be referring to the past or to a symbol of where she is at the time of writing – in lock-down. She’s rattled when a neighbour offers her soup as if to a needy ‘at risk’ person (“Soup”) and uses the event to provide an assertion that we never remember how or when we’ve become ‘old’. Even so, she prefers honest plain words to pierce the ear of grief – ”Bridge” eschews rainbow imagery in favour of a direct admission of loss, in this case by referring to a lost pet. In “Bed” she writes of ‘sliding my worn self / into the waiting slot carved by long use’, but there is always insomnia to contend with when she wakes in time to hear the start of Radio 4 (“Drawing the Waters”). There is a good deal of word-play and even sly innuendo in “Ballistic” which demonstrate, among other things, total control.

Her poem in the National Gallery, “How Beautiful Are The Feet” is a perfect illustration of her two-sided achievement. A simple ‘tourist’ looking at the Gerrini Altarpiece will arrive at a contemplation of nature’s variety of feet (“God’s good at feet”) but there is another twist to finish on:

Lord, may the six feet that I end beneath

lie light as those that have amused me most,

the coot, the booby and the Holy Ghost.

There are few poems in the canon written in praise of spam, a nettle-omelet, roadworks or a collection of stones with sad faces – but they’re all here, along with a few about cats. In particular, her perfect sonnet on “The Skip” laces the familiar down-sizing with a Drysdalian final couplet:

To see the back of it should bring relief

and not this synthesis of guilt and grief.

There’s a group of elegiac poems near the end which might be missed in a hurried reading: “Reclaiming the Abandoned Garden”, “Toad”, “Upon a Snail” and “Kiftsgate” are as good as anything that went before: sufficiently light of touch to sneak up on the unwary – and all the more intense as a result. All of which reveals that she is an absolute master of the well-made poem. Time and again she will go from the ordinary to the crafted in a blink. “Sticks” is testimony to her method:

That’s how I’ll spend the Winter. In the shed

with the autumn harvest of possibles.

The well-oiled walking sticks that will emerge ‘anointed’ are made to tread quietly: ‘no Blind-Pew tapping to create unease’. Feeling Unusual is a remarkable transformation of a sometimes unlikely set of quotidian possibles. When Drysdale writes about fading and weakening she seems to become stronger in doing so.

Oct 17 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Ann Drysdale

Poetry review – FEELING UNUSUAL: John Forth gets to grips with Ann Drysdale‘s vivid imagery and imagination

With an impressive Mari Lwyd striding across the cover (painted by Allison Neal) Ann Drysdale’s latest collection introduces an ‘imaginary friend’ who sometimes sounds like a poet. Ann Drysdale is not widely known for ‘wassailing’ and this particular hobby-horse translates either as ‘blessed Mary’ or ‘grey mare’, but the point of the device, traditionally, is to request entry for the price of a song around Christmas time or the Winter Solstice. So be it. A bit of fun and potentially a teasing metaphor:

But the dance is fast and the road is long and sometimes I need to catch my breath so I stop at your door and I sing my song of the old illusions of life and death. I’ll sing it for you and then I’ll knock: Here I am, O my next of kin – and you will turn the key in the lock to keep me out or bring me in. (“Mari Lwyd Dances”)After this ghostly opening, the second poem “Setting Off” is more down-to-earth and spoken by the rider:

She’s now on a bike (there are pedals) but manages ‘a non-existent trot’; expects to ‘pass unseen’ but everything remains precarious:

Next, Mari becomes a vehicle for observing the growth of a poet:

I will knock on her door till she remembers that she was once the Little Grey Pony, whispering stories of her own adventures into the busy silence of her head. (“Mari Lwyd Calls on a Kindred Spirit”)The third person host occasionally transformed herself into Mari when she would ‘make a wild mane of her cropped hair / to toss in time to her private whinnying’. By the time we reach the fourth Mari poem it is becoming clear that her dozen or so appearances will provide a skeletal framework for the book as a whole. In “Mari Lwyd Finds the Forgotten Horses” she is operating in a kind of limbo of ‘aborted horses in their various stages of completion’ though they never quite ran. They were ‘dreamed up and discarded’ but are nevertheless accessible to the Mari Lwyd:

This is perhaps the most mysterious of the Mari Lwyd poems, veering between a child’s dream of horses and discarded or unfinished poems. I’m not sure the ambiguity is a productive one. “Mari Lwyd Mends the Horses of Matholych”, shown in English and in Welsh, is a raid on the bloody tale of Branwen from the second branch of the Mabinogi. In the story the ruined horses are brought back to life by the use of a magic cauldron. So nothing is lost, nothing wasted. There follows a poem about ‘the postal palaver’ of a mini-mari sent to her (by ‘Nige’) in the post, delayed because it was a small parcel and not a large letter! Here, Mari has to come to terms with modern red tape which might be the reason for ‘her long face’. She’s now become an opportunity to tell an old joke.

Indeed Mari’s contemporary existence goes way beyond the original ‘skull on a broomstick / bobbing above a man clad in a sack’ – or what Sheenagh Pugh (via Mariott Edgar) calls ‘a stick with an ‘orse’s ‘ead ‘andle’. She has now become ‘a bedecked, bejewelled artifact / lit from within (“Mari Lwyd with Bells and Whistles”). The speaker generously concludes that ‘enthusiasm justifies the theft’. Before Mari takes her final curtain she will make an appearance as a kind of grim reaper, the host dispensing with her customary skills to pull out the cloth from under some gathered fine bone china to provide ‘a long crash of desolation’ (“Mari Lwyd Will Be Coming Soon”). They are still together for the poem “Seat” in which ‘She has grown old / little by little in my company’ and in “Badge of Honour” – now become a walking stick with ‘a jolly knob’ stuck on the end:

She awards herself ‘the Order of the Staircase’ (viz L’esprit de L’escalier) for ‘thinking of a thing I should have said / moments after the moment when I didn’t’. Always the grand idea is paired with a debunking that keeps self-parody in the frame. Similarly, in “The Gravedigger Digs the Difference” she calls upon Hamlet to bolster a claim that the tools of working men (her own tools) are straightforward to those who use them:

Both sequence and book end with a pantomime performance (“Mari Lwyd Meets Marie Lloyd”) – a prose poem in which all of these steps are retraced before an invisible audience: ‘I don’t know who you are, but one look at those teeth tells me we must be related’. For the Curtain Call, ‘Marie is bareheaded, grey-haired and walking with a stick. Mari is now wearing Marie’s hat. They are both transformed’.

*

It is typical of Ann Drysdale that, in this her eighth collection, a liberating sense of humour accompanies dark foreboding pieces about ordinary stuff. It’s as if we’re invited into a mythical, other-worldly place in order to foreground what’s actually going on in the day-to-day of covid isolation, intermittent loneliness and loss. The back cover tells us she once lived on a narrow boat, but here, in “Boat”, she could be referring to the past or to a symbol of where she is at the time of writing – in lock-down. She’s rattled when a neighbour offers her soup as if to a needy ‘at risk’ person (“Soup”) and uses the event to provide an assertion that we never remember how or when we’ve become ‘old’. Even so, she prefers honest plain words to pierce the ear of grief – ”Bridge” eschews rainbow imagery in favour of a direct admission of loss, in this case by referring to a lost pet. In “Bed” she writes of ‘sliding my worn self / into the waiting slot carved by long use’, but there is always insomnia to contend with when she wakes in time to hear the start of Radio 4 (“Drawing the Waters”). There is a good deal of word-play and even sly innuendo in “Ballistic” which demonstrate, among other things, total control.

Her poem in the National Gallery, “How Beautiful Are The Feet” is a perfect illustration of her two-sided achievement. A simple ‘tourist’ looking at the Gerrini Altarpiece will arrive at a contemplation of nature’s variety of feet (“God’s good at feet”) but there is another twist to finish on:

There are few poems in the canon written in praise of spam, a nettle-omelet, roadworks or a collection of stones with sad faces – but they’re all here, along with a few about cats. In particular, her perfect sonnet on “The Skip” laces the familiar down-sizing with a Drysdalian final couplet:

There’s a group of elegiac poems near the end which might be missed in a hurried reading: “Reclaiming the Abandoned Garden”, “Toad”, “Upon a Snail” and “Kiftsgate” are as good as anything that went before: sufficiently light of touch to sneak up on the unwary – and all the more intense as a result. All of which reveals that she is an absolute master of the well-made poem. Time and again she will go from the ordinary to the crafted in a blink. “Sticks” is testimony to her method:

The well-oiled walking sticks that will emerge ‘anointed’ are made to tread quietly: ‘no Blind-Pew tapping to create unease’. Feeling Unusual is a remarkable transformation of a sometimes unlikely set of quotidian possibles. When Drysdale writes about fading and weakening she seems to become stronger in doing so.