Poetry review – BLOOD SUGAR, SEX, MAGIC: Stephen Claughton is convinced by the authenticity of Sarah James’s poems gathered around the experience of living with diabetes

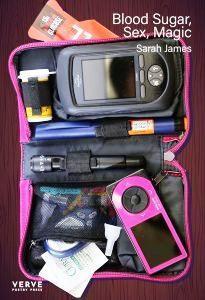

Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic

Sarah James

Verve Poetry Press

ISBN 978-1-913917-11-1

£10.99

Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic

Sarah James

Verve Poetry Press

ISBN 978-1-913917-11-1

£10.99

Although not all the poems deal explicitly with the condition (‘many are also about everyday aspects of “normal” life: siblingship, friendship, love, sex, parenthood, identity, aging, pain, loss and happiness …’), Sarah James’s fifth full collection centres on her experience of living with type one diabetes, which – she says in her foreword – it has taken her nearly forty years to come even close to accepting.

The opening prose poem, “Diagnosis”, perfectly captures the feeling of abandonment, when she was first diagnosed in hospital at the age of six. It begins with her being cocooned in her father’s car (‘The only colour is Dad’s Ford Cortina, his bright maroon pride and joy’) and ends: ‘Dad’s Cortina was a livid bruise in the car park. But, since it’s gone, I wish it back. The hospital’s white walls close around me.’ The poem mixes childhood impressions with factual information. After showering the letters D-I-A-B-E-T-E-S across the page (‘For weeks afterwards, everything blizzards … I can’t yet string together the letters and sounds of this oddness’), she goes on:

… I will come to understand it as a list of sweet

things I should never eat. I will learn to measure ‘better’

in glass syringes, injecting oranges and then my leg. I

will will my skin numb.

The poems about diabetes that follow fall broadly into two categories: those that use experimental techniques, reminiscent of the author’s 2015 collection, The Magnetic Diaries, to try and capture her experience of illness; and those that deal more conventionally, clinically even, with the practicalities of living with the condition. Part of “How to become your own worst friend” is relegated to footprints, arranged to make sense when read together, perhaps encapsulating the fact that diabetes is a hidden disease. The title of another uses typographical effects which I took to replicate not just its hiddenness, but the genetic flaws that cause it. The poem itself is impressionistic:

it howls through the bricked-up chimney

spits soot, smoke and burnt feathers

hisses from the stone-cold iron

whistles steam from an empty kettle

In contrast to these examples there are more mainstream poems:

The glass syringe is heavy.

I teach my fingers to force

the needle deep into an orange.

Then I press in the plunger’s

citrus sting of cold insulin

(“Admitted Nov 30, 1981, age 6: diabetes mellitus”)

or:

In the old young days: piss

on diastix, and a glass syringe

twice the length of my palm.

(“Thick-skinned, Thin-fleshed”)

The experimental poems are interesting, but as James says in her foreword: ‘Accurately describing life with type one diabetes is difficult. Real understanding probably only comes with first-hand experience and no one would wish that on anyone.’

Other poems reflect the way in which diabetes impinges on everyday life. The title poem starts with preparations for sex:

First, I check my sugar levels are good.

He chooses the tunes; I set incense burning.

(“Blood Sugar Sex Magic”)

(It tactfully fades out at the end with words and phrases getting fainter on the page.) Some poems do not mention diabetes at all. The preceding poem, “Promise”, is purely erotic.

Several poems are haunted by an older sister, who

died before I was born,

less than an hour’s worth of air

in her soaked-tissue lungs,

slowly filling with water.

I still feel like I’m drowning

(“Twist”).

Some of these are experimental (“my [dead] sister’s advice:” consists of phrases using ‘bone’ from which the key word has been filleted). Others are more straightforward, although the relationship itself remains complicated. She’s a ‘ghost sibling her nearest to a best friendship’, but also ‘The girl who isn’t my sister / won’t stop laughing / at the narrative she’s made of me’. James imagines her saying, ‘I’d have lived this world better’. She conjures up a real sibling relationship, involving love and hate as well as rivalry. There’s a nagging sense of ‘what if?’, as in “Questions not to ask my dead sister”.

In addition to the symptoms she already suffers from (vividly described in “Diabetes’ unWell of Night Hypos*”), there is the fear of what the illness might bring (a grandfather lost both a leg and his sight as a result of diabetes):

No DNA dissection

can decode my human genetics

into a definitive date of death marker.

My only accurate prediction then: I’m afraid,

if it did, I wouldn’t know how to treat the answer.

(“Prognosis”)

The key is loss of control (‘But how can anyone control / their blood sugars, // when they can’t control / the world around them?’). Many of the poems not specifically about diabetes deal with other kinds of vulnerability. “People Scare Me Because …” carries the epigraph, ‘“shows some traits of avoidant personality or Asperger’s”’, and begins:

They’re like milk bottles

on winter doorsteps: contents

distanced by glass and frozen

to my touch. …

There is a vivid account of childbirth (“Safe Harbour”) and poems about driving through a blizzard, being lost in the mist and the hazards of cycling.

There is also humour – for instance, in “Doing the School Run with Freud”, or “Questions not to ask a diabetic”, which deals with a particularly crass interlocutor:

Can you still have sex?

Yes. But not with you.

Would I catch it?

It’s not an infectious disease; my fist

might catch your chin though…

who nevertheless hits the mark with:

Why isn’t it curable?

Good question. For years, folks have promised

it will be soon. Maybe ask Big Pharma.

James has some wonderfully off-beat imagery:

I have lived the life of a fish

vacuum-packed in plastic,

frozen in white ice

(“The life of a fish”)

or:

Our orphan-thoughts drawer is crammed

with paired memories that don’t quite match.

(“Replacing the Irreplaceable”)

And some of the poems are positively surreal (“A Catching Smile” begins, ‘Imagine your smile is a scrap / of part-written paper blown / petal-wet through splattered streets’; and “Mâché” starts, ‘A papier-mâché woman, / I view myself as a ramshackle house’). Yet she also provides precise descriptions of the natural world:

Moorhens snip the surface; a swan ruffles up a lace dress

with her feather-stitched wake towards her reed-moored nest.

Shimmering light hides the fast paddling beneath, the deeper

flit of fish, and other sunken secrets – rusted metal re-

sculpted by weed.

(“Along the Edge”)

Nature is a source of comfort. ‘Here, I’ve no need for frog-princes – the canal carries my love without spilling,’ she says in the same poem. Fairy tales are referred to a number of times: as well as “The Frog Prince”, there are mentions of “Little Red Riding Hood”, “The Ugly Duckling”, “Cinderella”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Princess and the Pea”.

In the end, James does manage, in her own words, to ‘come close to accepting’ her condition. ‘Not all of my childhood was illness,’ she says at the end of “Freshly Baked” (about her mother making bread) and the book ends with a poem called “Self-forgiveness”:

And yes, it’s true

that perhaps I’ve come

to love this ‘fault’

that I hate most,

not for the disability,

but through accepting

that without it,

what little would remain

of the me

I’ve come to see.

Although focused on a particular theme, Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic is a varied collection, both in its subject matter and technique. These are honest, heartfelt poems that bring together the experimental and more mainstream strands of Sarah James’s writing, which were for the most part segregated between her last two collections, The Magnetic Diaries and plenty- fish (both published in 2015). They were accomplished books, although my impression of the latter (written as part of a poetry MA course) is that what it may have gained in sophistication and polish it perhaps lost in character and individuality. Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic, on the other hand, is written very much in the poet’s own voice.

Sep 15 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Sarah James

Poetry review – BLOOD SUGAR, SEX, MAGIC: Stephen Claughton is convinced by the authenticity of Sarah James’s poems gathered around the experience of living with diabetes

Although not all the poems deal explicitly with the condition (‘many are also about everyday aspects of “normal” life: siblingship, friendship, love, sex, parenthood, identity, aging, pain, loss and happiness …’), Sarah James’s fifth full collection centres on her experience of living with type one diabetes, which – she says in her foreword – it has taken her nearly forty years to come even close to accepting.

The opening prose poem, “Diagnosis”, perfectly captures the feeling of abandonment, when she was first diagnosed in hospital at the age of six. It begins with her being cocooned in her father’s car (‘The only colour is Dad’s Ford Cortina, his bright maroon pride and joy’) and ends: ‘Dad’s Cortina was a livid bruise in the car park. But, since it’s gone, I wish it back. The hospital’s white walls close around me.’ The poem mixes childhood impressions with factual information. After showering the letters D-I-A-B-E-T-E-S across the page (‘For weeks afterwards, everything blizzards … I can’t yet string together the letters and sounds of this oddness’), she goes on:

The poems about diabetes that follow fall broadly into two categories: those that use experimental techniques, reminiscent of the author’s 2015 collection, The Magnetic Diaries, to try and capture her experience of illness; and those that deal more conventionally, clinically even, with the practicalities of living with the condition. Part of “How to become your own worst friend” is relegated to footprints, arranged to make sense when read together, perhaps encapsulating the fact that diabetes is a hidden disease. The title of another uses typographical effects which I took to replicate not just its hiddenness, but the genetic flaws that cause it. The poem itself is impressionistic:

In contrast to these examples there are more mainstream poems:

or:

The experimental poems are interesting, but as James says in her foreword: ‘Accurately describing life with type one diabetes is difficult. Real understanding probably only comes with first-hand experience and no one would wish that on anyone.’

Other poems reflect the way in which diabetes impinges on everyday life. The title poem starts with preparations for sex:

(It tactfully fades out at the end with words and phrases getting fainter on the page.) Some poems do not mention diabetes at all. The preceding poem, “Promise”, is purely erotic.

Several poems are haunted by an older sister, who

died before I was born, less than an hour’s worth of air in her soaked-tissue lungs, slowly filling with water. I still feel like I’m drowning (“Twist”).Some of these are experimental (“my [dead] sister’s advice:” consists of phrases using ‘bone’ from which the key word has been filleted). Others are more straightforward, although the relationship itself remains complicated. She’s a ‘ghost sibling her nearest to a best friendship’, but also ‘The girl who isn’t my sister / won’t stop laughing / at the narrative she’s made of me’. James imagines her saying, ‘I’d have lived this world better’. She conjures up a real sibling relationship, involving love and hate as well as rivalry. There’s a nagging sense of ‘what if?’, as in “Questions not to ask my dead sister”.

In addition to the symptoms she already suffers from (vividly described in “Diabetes’ unWell of Night Hypos*”), there is the fear of what the illness might bring (a grandfather lost both a leg and his sight as a result of diabetes):

The key is loss of control (‘But how can anyone control / their blood sugars, // when they can’t control / the world around them?’). Many of the poems not specifically about diabetes deal with other kinds of vulnerability. “People Scare Me Because …” carries the epigraph, ‘“shows some traits of avoidant personality or Asperger’s”’, and begins:

There is a vivid account of childbirth (“Safe Harbour”) and poems about driving through a blizzard, being lost in the mist and the hazards of cycling.

There is also humour – for instance, in “Doing the School Run with Freud”, or “Questions not to ask a diabetic”, which deals with a particularly crass interlocutor:

Can you still have sex? Yes. But not with you. Would I catch it? It’s not an infectious disease; my fist might catch your chin though…who nevertheless hits the mark with:

Why isn’t it curable? Good question. For years, folks have promised it will be soon. Maybe ask Big Pharma.James has some wonderfully off-beat imagery:

or:

And some of the poems are positively surreal (“A Catching Smile” begins, ‘Imagine your smile is a scrap / of part-written paper blown / petal-wet through splattered streets’; and “Mâché” starts, ‘A papier-mâché woman, / I view myself as a ramshackle house’). Yet she also provides precise descriptions of the natural world:

Nature is a source of comfort. ‘Here, I’ve no need for frog-princes – the canal carries my love without spilling,’ she says in the same poem. Fairy tales are referred to a number of times: as well as “The Frog Prince”, there are mentions of “Little Red Riding Hood”, “The Ugly Duckling”, “Cinderella”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Princess and the Pea”.

In the end, James does manage, in her own words, to ‘come close to accepting’ her condition. ‘Not all of my childhood was illness,’ she says at the end of “Freshly Baked” (about her mother making bread) and the book ends with a poem called “Self-forgiveness”:

Although focused on a particular theme, Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic is a varied collection, both in its subject matter and technique. These are honest, heartfelt poems that bring together the experimental and more mainstream strands of Sarah James’s writing, which were for the most part segregated between her last two collections, The Magnetic Diaries and plenty- fish (both published in 2015). They were accomplished books, although my impression of the latter (written as part of a poetry MA course) is that what it may have gained in sophistication and polish it perhaps lost in character and individuality. Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic, on the other hand, is written very much in the poet’s own voice.