Poetry review – FAULTLINES: Alex Josephy reviews a varied but well-integrated collection by Caroline Maldonado

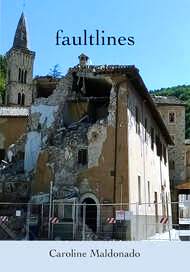

faultlines

Caroline Maldonado

Vole Books 2022

ISBN: 978-1-913329-67-9

£10

faultlines

Caroline Maldonado

Vole Books 2022

ISBN: 978-1-913329-67-9

£10

I can hardly believe that this is Maldonado’s first full collection. She is well known for her work as an award winning poetry translator and as a former chair of the Board of Trustees for Modern Poetry in Translation. And the poems in this collection are as sure-footed and delightful as might be expected by anyone familiar with her translations.

The collection is composed of three sequences: ‘Faultlines’, poems concerning the 2016 earthquakes in Le Marche in central Italy; ‘The Creek Men’, a meditation on Lawrence Edwards’ beautiful and mysterious East Anglian marshland sculptures; and ‘Interiors’, a sequence haunted, as are other parts of the collection, by the Holocuast, the long shadows it still casts and the threatening legacy of Fascism that does not go away.

There is coherence between the three sections; Maldonado’s poems speak in different contexts about powerful natural and historical forces, disaster and restoration, with an eye on constant alert for what is beautiful and what is painful. There are exhilarating moments in these poems where something that can’t quite be explained, by its very nature gives hope. For instance, the ‘Pilgrims’ in the poem of that name, wander into a mysterious and mythically haunted gorge, from which:

…we returned, every one of us, and we were changed

though could not speak of it, neither what we sought

nor if we’d found it, where we’d been or why.

I am strongly drawn to these poems because I too was living in Italy around the time of the earthquakes. I travelled to Le Marche a year later, not to be a disaster sightseer but to meet a cousin. So much of of what Maldonado describes is exactly as I remember it, that it’s hard to write critically about the poems, other than to note how very skillfully and with what compassion they expose what happened, what went wrong after the quakes, and the extraordinary way in which ordinary people in the region eventually picked up their lives and found ways forward.

‘Faultlines’, while tracing the 2016 disaster, also conveys a broader, affectionate but clear-sighted vision of contemporary Italy. Maldonado gives exactly the right amount of detail, sharply defined but never remotely sentimental. I loved the landscape and close observation of horses in ‘Horses above the lake of Cingoli’, a poem that to my mind refreshes and completely vindicates the use of simile. Reading, I feel the breath of those horses on my hand:

One always stands alone.

Their noses are soft as doves,

their lips pass like shadows

across my palm.

On the other side of a societal faultline, we encounter Italy’s dispossessed. A Tuareg asylum seeker, identified as a musician, sells small personal possessions on a pavement in Naples. A victim of Boko Haram has lost her child and, arriving in Italy and falling foul of muggers, her man too. In spare, heartbreaking lines, Maldonado shows that such people have everything to mourn:

She will wash her man’s body ready for burial.

She will drink the water she washed him in.

In another poem, two linked and subtly half-rhymed sonnets balance the discovery of a granite water goddess off the coast of Alexandria against the drowning of refugees from a precarious dinghy on the same sea. The solidity of the poem’s form shares and somehow deepens the gravity of each of the two stories.

The sequence leads toward the earthquake itself via a beautiful ‘Kite-surfer’, whose fall provokes a sense of the Icarus in all of us:

…Each one of us thinks of what’s failing

or failed, dying or on the brink: we mourn our lost rapture.

The poems that follow move more or less chronologically through the events of October 2016. I remember being as transfixed as Maldonado is by the precise timing of events, as reported in all the Italian newspapers:

A campanile slants over rubble, its clock-hands stuck

at 3.38 by which time a child’s gone, one foot shoeless.

The poems cluster around the disaster in a variety of forms, as if seeking a voice in which to vent feelings of shock, disbelief and fury at the lack of an effective government response. Life does go on, though; the mountains retain their shapes and the goats continue to walk there, and people set up improvised dwellings, ‘cubicles for temporary toilets. pine huts/a bar selling cappuccinos, fresh pastry…’ I was also moved by the poem about the subsequent avalanche, in which the land’s collapse becomes even more closely linked to personal experience:

There were those among us who crumbled

all at once (just like the innocent mountain…

and the comfort of songs of resistance that reach back into Italy’s difficult past:

…We chose

songs that all could share – the ones partisans

sang came soonest to our minds.

This sequence encompasses moments of despair, moving toward a powerful sestina on drought and the loss of water security, which will most likely become truer with every passing year. I also loved, though, the account of restorers who came to the zona rossa, the danger zone, in order to find and begin painstaking repairs to works of art.

The second section of the book, ‘The Creek Men’, takes us to a very different setting but fits well into Maldonado’s overarching themes. It’s worth looking up and even making a journey to visit Lawrence Edwards’ evocative East Anglian pieces, arising out of mud, reeds and other natural materials, cast in bronze and then positioned so as to meld back into the landscape. Here, human experience and other natural phenomena meet, tangle and sometimes merge. Maldonado finds a kind of leveling in this work, and a celebration of ordinary people, not forgotten although ‘chucked loose in a common grave.’

I can’t help thinking of Heaney’s bog people. Like them, these pieces speak of histories, injustices, and endurance. Tides and weather effect a marsh-change, but do not render Lawrence’s figures inhuman:

All day they carry our remains

and wear our faces.

And like Heaney’s beheaded girl in Strange Fruit ‘outstaring/what had begun to feel like reverence’, Maldonado’s vision of a Lawrence figure resurrected on a city street affords him the power to disturb and challenge:

In the dim corner of a railway station

you’ll come across him, a heap,

his crooked branch-arm stretched out.

The book’s final section ranges a little more widely, returning to the legacy of Holocaust, its echoes in present day racism, and to ekphrasis, reflecting on artistic process.

Each portrait reflects the desolation

of the painter’s gaze…

…

Lean in close

as if to your bathroom mirror

(‘Lorenzo Lotto’s Portraits’)

The final poem, ‘Goethe in Rome,’ is a fitting place to end. It could be said to be doubly ekphrastic; in Tischbein’s sketch, Goethe observes the street outside his window with the eye of a poet, and Maldonado borrows his gaze. She sees ‘what he sees’, through two lenses – that of the artist making the portrait, and that of the poet in the portrait – and gives us the small details of ordinary life, illuminated; light, houses and roofs ‘alive against the sky.’ This, she might be saying, is what poetry can do.

Sep 6 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Caroline Maldonado

Poetry review – FAULTLINES: Alex Josephy reviews a varied but well-integrated collection by Caroline Maldonado

I can hardly believe that this is Maldonado’s first full collection. She is well known for her work as an award winning poetry translator and as a former chair of the Board of Trustees for Modern Poetry in Translation. And the poems in this collection are as sure-footed and delightful as might be expected by anyone familiar with her translations.

The collection is composed of three sequences: ‘Faultlines’, poems concerning the 2016 earthquakes in Le Marche in central Italy; ‘The Creek Men’, a meditation on Lawrence Edwards’ beautiful and mysterious East Anglian marshland sculptures; and ‘Interiors’, a sequence haunted, as are other parts of the collection, by the Holocuast, the long shadows it still casts and the threatening legacy of Fascism that does not go away.

There is coherence between the three sections; Maldonado’s poems speak in different contexts about powerful natural and historical forces, disaster and restoration, with an eye on constant alert for what is beautiful and what is painful. There are exhilarating moments in these poems where something that can’t quite be explained, by its very nature gives hope. For instance, the ‘Pilgrims’ in the poem of that name, wander into a mysterious and mythically haunted gorge, from which:

I am strongly drawn to these poems because I too was living in Italy around the time of the earthquakes. I travelled to Le Marche a year later, not to be a disaster sightseer but to meet a cousin. So much of of what Maldonado describes is exactly as I remember it, that it’s hard to write critically about the poems, other than to note how very skillfully and with what compassion they expose what happened, what went wrong after the quakes, and the extraordinary way in which ordinary people in the region eventually picked up their lives and found ways forward.

‘Faultlines’, while tracing the 2016 disaster, also conveys a broader, affectionate but clear-sighted vision of contemporary Italy. Maldonado gives exactly the right amount of detail, sharply defined but never remotely sentimental. I loved the landscape and close observation of horses in ‘Horses above the lake of Cingoli’, a poem that to my mind refreshes and completely vindicates the use of simile. Reading, I feel the breath of those horses on my hand:

One always stands alone. Their noses are soft as doves, their lips pass like shadows across my palm.On the other side of a societal faultline, we encounter Italy’s dispossessed. A Tuareg asylum seeker, identified as a musician, sells small personal possessions on a pavement in Naples. A victim of Boko Haram has lost her child and, arriving in Italy and falling foul of muggers, her man too. In spare, heartbreaking lines, Maldonado shows that such people have everything to mourn:

In another poem, two linked and subtly half-rhymed sonnets balance the discovery of a granite water goddess off the coast of Alexandria against the drowning of refugees from a precarious dinghy on the same sea. The solidity of the poem’s form shares and somehow deepens the gravity of each of the two stories.

The sequence leads toward the earthquake itself via a beautiful ‘Kite-surfer’, whose fall provokes a sense of the Icarus in all of us:

The poems that follow move more or less chronologically through the events of October 2016. I remember being as transfixed as Maldonado is by the precise timing of events, as reported in all the Italian newspapers:

The poems cluster around the disaster in a variety of forms, as if seeking a voice in which to vent feelings of shock, disbelief and fury at the lack of an effective government response. Life does go on, though; the mountains retain their shapes and the goats continue to walk there, and people set up improvised dwellings, ‘cubicles for temporary toilets. pine huts/a bar selling cappuccinos, fresh pastry…’ I was also moved by the poem about the subsequent avalanche, in which the land’s collapse becomes even more closely linked to personal experience:

and the comfort of songs of resistance that reach back into Italy’s difficult past:

This sequence encompasses moments of despair, moving toward a powerful sestina on drought and the loss of water security, which will most likely become truer with every passing year. I also loved, though, the account of restorers who came to the zona rossa, the danger zone, in order to find and begin painstaking repairs to works of art.

The second section of the book, ‘The Creek Men’, takes us to a very different setting but fits well into Maldonado’s overarching themes. It’s worth looking up and even making a journey to visit Lawrence Edwards’ evocative East Anglian pieces, arising out of mud, reeds and other natural materials, cast in bronze and then positioned so as to meld back into the landscape. Here, human experience and other natural phenomena meet, tangle and sometimes merge. Maldonado finds a kind of leveling in this work, and a celebration of ordinary people, not forgotten although ‘chucked loose in a common grave.’

I can’t help thinking of Heaney’s bog people. Like them, these pieces speak of histories, injustices, and endurance. Tides and weather effect a marsh-change, but do not render Lawrence’s figures inhuman:

And like Heaney’s beheaded girl in Strange Fruit ‘outstaring/what had begun to feel like reverence’, Maldonado’s vision of a Lawrence figure resurrected on a city street affords him the power to disturb and challenge:

The book’s final section ranges a little more widely, returning to the legacy of Holocaust, its echoes in present day racism, and to ekphrasis, reflecting on artistic process.

Each portrait reflects the desolation of the painter’s gaze… … Lean in close as if to your bathroom mirror (‘Lorenzo Lotto’s Portraits’)The final poem, ‘Goethe in Rome,’ is a fitting place to end. It could be said to be doubly ekphrastic; in Tischbein’s sketch, Goethe observes the street outside his window with the eye of a poet, and Maldonado borrows his gaze. She sees ‘what he sees’, through two lenses – that of the artist making the portrait, and that of the poet in the portrait – and gives us the small details of ordinary life, illuminated; light, houses and roofs ‘alive against the sky.’ This, she might be saying, is what poetry can do.