Poetry review – WHERE THE DEAD WALK: Mat Riches finds Angela Kirby’s poems enjoyably unsettling with their shifts of mood and focus

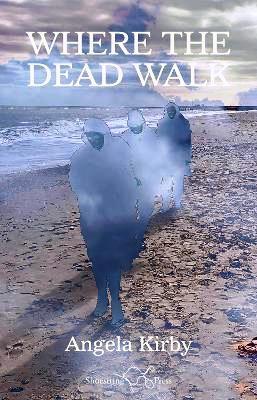

Where The Dead Walk

Angela Kirby

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9781912524990

68pp £10

Where The Dead Walk

Angela Kirby

Shoestring Press

ISBN 9781912524990

68pp £10

Where The Dead Walk is Angela Kirby’s sixth poetry collection since 2004 (if we include a New & Selected from 2015) , so it’s fair to say we should find ourselves in safe hands; and looking at the list of acknowledgements at the start of the book we can see that a number of the poems have been published in reputable magazines and online journals—including this very publication and here (and please note that one of these linked poems doesn’t feature in the book, so it’s something of a collector’s item).

It’s interesting to note that Kirby’s safe hands have kept themselves busy. Between 2020 when London Grip first published ‘3 AM’ and 2022 when this collection appeared, Kirby has revised the poem further, so that what once read “no moon, no stars, no sirens / no cat yowls, no dog howls” now has the word “wails” at the start of the second line. It seems apt to be adding that word to a book called Where the Dead Walk.

According to the blurb by Patricia McCarthy, the collection is described as covering “Nostalgia, regret and celebration”, and it’s fair say that all three of these themes are well represented, sometimes even in the same poem. A particular example of this is ‘Father’, where the protagonist (and I’m pretty sure it’s Kirby) admits to approaching the age she lost her father. The second stanza of the poem definitely manages to pack in both nostalgia and celebration.

I would like to hold your hand

be caught up on your arms again

wrapped up in the sold safe smell

of tweed, tobacco, Knight’s Castille.

While you could argue that this stanza also supplies regret, it’s certainly there in the final stanza of the poem.

Father, where are you?

Will you wait for me?

Can you forgive me?

Those question marks culminate in the final line: is there regret in the request for forgiveness; was the young child somehow partly responsible? Or is it a case of wanting forgiveness for not knowing where he is?

There is some evidence elsewhere in the collection that Kirby has a religious leaning, for example in ‘A Small Precipitation’ there’s a suggestion of a convent-based upbringing. The poem describes an argument among angels causing a “dumping [of] rain, snow and hail as they fell.” while here in the corporeal world

[…] Mother says

we should own-up but none of us will admit

to those Impure Thoughts and Immodest Acts

she bangs on about, sins that shame our parents

and stain our souls. All those decades ago

but even now, dark clouds still unsettle me.

You could perhaps wonder if these specific sins are the ones referred to in ‘Father’; but I suspect they are not. There are further religious references in ‘A Disciple Has Reservations’, but the clearest and perhaps most up to date is in the final poem,’Pandemic Plea, Prayer Or Polite Request’ in which the circa 90-year old Kirby requests longer on earth. “Oh may it not be yet, Lord”, but when it does come may it be “fleet”.

For all its joviality and delight in gentle ribbing of religion, there are some quite brutal moments in the book, moments where you are pulled up short and can see how events from the past stay with us. The first five poems all deal with the decline and or death of both of Kirby’s parents, and these are all haunting, frank, elegiac and shocking in equal parts. However, my eyes were drawn more to the poems that look back at Kirby’s own life, and in particular ‘A Present From Wales’, which would be a lovely poem about a family train trip to Wales with its mentions of “long dreamed / of sea a silver edge to our horizon” were it not for the stanza.

Our first holiday, we took the express to Holyhead, and then

the little train. Did I dream the woman falling through that

half-open window, her blood across the pane? 'Don’t look'

my mother said, and turned my face away into her lap.

The poem goes on across five more stanzas to describe a glorious holiday, a “lucky dip of pebbles into our waiting pails / I have some here on my window sill, A Present from Wales.” However, in the seventh and final stanza the poem revisits the bloodied woman of the first stanza, ending with the chilling line “It is hard to throw souvenirs away.” I am going to go out on a limb here and suggest she doesn’t mean the pebbles on the windowsill.

Surreal and violent moments and hints are dotted throughout the collection. Key examples of this can be found in poems like ‘The Crossing Keeper’, where we learn of the titular character that “ten years before, the down train / took his arm, but the pain still nagged it / when the wind was east”. However, the most shocking of these and perhaps the most masterfully presented, saving, as it does, the big reveal to the end is ‘The Lane’. Notionally it’s a poem that describes a walk down the lane a tour round some village – “If it had another name we never knew it”. But for all of the beautiful descriptions of going

past woods where lovers

held their trysts, past the village school

where Miss Gornall held sway over

neat rows of well-drilled children

chanting long Litanies of the Saints

and Times Tables

there’s a shock when we reach the end of the poem and are told that if we’d turned right instead of left we’d have reached the main road.

seeing always

the face of the boy who died there

beneath the wheels of the Preston bus.

It feels a bit wrong to be giving the game away, but I present this ending as a way of showing how a Kirby poem can turn on the proverbial sixpence. Where there is light and brevity we are only a few lines way from something darker. The book is laden with examples of this, and never more so than in something like ‘Southerners’. Here the poet’s northern father takes an initial dislike to Kirby’s future husband when she brings him home to meet the family; but the feckless Southerner manages to make a good impression by fixing the lights after a power failure. “‘Sithee, ‘oo could tell, yon chinless / booger’s not so gormless as ‘ee looks’. So far, so good you think, until Kirby reflects later on in life on her father’s initial assessment “it was years before / I realised that he’d been right first time”.

Such is this trick of Kirby’s that the ending of the poem that follows ‘Southerners’ in the collection feels almost like an ars poetica. ‘The Reality of Eagles’ describes these glorious birds and “the grandeur of their wings”. The final four lines of an eight line poem are

how they subjugate the air

and the space between mountains

their shadows hovering

between us and the sun.

A lot of the poems in this collection feel like those last four lines. This is a good thing. This is an excellent collection written by a poet in total control of her craft.

Sep 27 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Angela Kirby

Poetry review – WHERE THE DEAD WALK: Mat Riches finds Angela Kirby’s poems enjoyably unsettling with their shifts of mood and focus

Where The Dead Walk is Angela Kirby’s sixth poetry collection since 2004 (if we include a New & Selected from 2015) , so it’s fair to say we should find ourselves in safe hands; and looking at the list of acknowledgements at the start of the book we can see that a number of the poems have been published in reputable magazines and online journals—including this very publication and here (and please note that one of these linked poems doesn’t feature in the book, so it’s something of a collector’s item).

It’s interesting to note that Kirby’s safe hands have kept themselves busy. Between 2020 when London Grip first published ‘3 AM’ and 2022 when this collection appeared, Kirby has revised the poem further, so that what once read “no moon, no stars, no sirens / no cat yowls, no dog howls” now has the word “wails” at the start of the second line. It seems apt to be adding that word to a book called Where the Dead Walk.

According to the blurb by Patricia McCarthy, the collection is described as covering “Nostalgia, regret and celebration”, and it’s fair say that all three of these themes are well represented, sometimes even in the same poem. A particular example of this is ‘Father’, where the protagonist (and I’m pretty sure it’s Kirby) admits to approaching the age she lost her father. The second stanza of the poem definitely manages to pack in both nostalgia and celebration.

While you could argue that this stanza also supplies regret, it’s certainly there in the final stanza of the poem.

Those question marks culminate in the final line: is there regret in the request for forgiveness; was the young child somehow partly responsible? Or is it a case of wanting forgiveness for not knowing where he is?

There is some evidence elsewhere in the collection that Kirby has a religious leaning, for example in ‘A Small Precipitation’ there’s a suggestion of a convent-based upbringing. The poem describes an argument among angels causing a “dumping [of] rain, snow and hail as they fell.” while here in the corporeal world

You could perhaps wonder if these specific sins are the ones referred to in ‘Father’; but I suspect they are not. There are further religious references in ‘A Disciple Has Reservations’, but the clearest and perhaps most up to date is in the final poem,’Pandemic Plea, Prayer Or Polite Request’ in which the circa 90-year old Kirby requests longer on earth. “Oh may it not be yet, Lord”, but when it does come may it be “fleet”.

For all its joviality and delight in gentle ribbing of religion, there are some quite brutal moments in the book, moments where you are pulled up short and can see how events from the past stay with us. The first five poems all deal with the decline and or death of both of Kirby’s parents, and these are all haunting, frank, elegiac and shocking in equal parts. However, my eyes were drawn more to the poems that look back at Kirby’s own life, and in particular ‘A Present From Wales’, which would be a lovely poem about a family train trip to Wales with its mentions of “long dreamed / of sea a silver edge to our horizon” were it not for the stanza.

The poem goes on across five more stanzas to describe a glorious holiday, a “lucky dip of pebbles into our waiting pails / I have some here on my window sill, A Present from Wales.” However, in the seventh and final stanza the poem revisits the bloodied woman of the first stanza, ending with the chilling line “It is hard to throw souvenirs away.” I am going to go out on a limb here and suggest she doesn’t mean the pebbles on the windowsill.

Surreal and violent moments and hints are dotted throughout the collection. Key examples of this can be found in poems like ‘The Crossing Keeper’, where we learn of the titular character that “ten years before, the down train / took his arm, but the pain still nagged it / when the wind was east”. However, the most shocking of these and perhaps the most masterfully presented, saving, as it does, the big reveal to the end is ‘The Lane’. Notionally it’s a poem that describes a walk down the lane a tour round some village – “If it had another name we never knew it”. But for all of the beautiful descriptions of going

there’s a shock when we reach the end of the poem and are told that if we’d turned right instead of left we’d have reached the main road.

It feels a bit wrong to be giving the game away, but I present this ending as a way of showing how a Kirby poem can turn on the proverbial sixpence. Where there is light and brevity we are only a few lines way from something darker. The book is laden with examples of this, and never more so than in something like ‘Southerners’. Here the poet’s northern father takes an initial dislike to Kirby’s future husband when she brings him home to meet the family; but the feckless Southerner manages to make a good impression by fixing the lights after a power failure. “‘Sithee, ‘oo could tell, yon chinless / booger’s not so gormless as ‘ee looks’. So far, so good you think, until Kirby reflects later on in life on her father’s initial assessment “it was years before / I realised that he’d been right first time”.

Such is this trick of Kirby’s that the ending of the poem that follows ‘Southerners’ in the collection feels almost like an ars poetica. ‘The Reality of Eagles’ describes these glorious birds and “the grandeur of their wings”. The final four lines of an eight line poem are

A lot of the poems in this collection feel like those last four lines. This is a good thing. This is an excellent collection written by a poet in total control of her craft.