What The Thunder Said: Brian Docherty reviews Ruth Valentine’s new collection IF YOU WANT THUNDER

If You Want Thunder

Ruth Valentine

Smokestack Books, 2021

ISBN 978-1-8381988-4-8.

£7.99

If You Want Thunder

Ruth Valentine

Smokestack Books, 2021

ISBN 978-1-8381988-4-8.

£7.99

This book, Ruth Valentine’s 10th collection, opens with a sonnet, ‘Past’ where we are told ‘Your task / is keep on walking.’ It’s not clear who the ‘you’ is here; and, whether it is a rhetorical address to the reader, or to someone in particular, this is typical of the book’s procedures, both formally and thematically. It is divided into six sections, and Section 1, ‘Sea-Fret’, starts with ‘Jettisoned’, a bleak, unflinching look at the cost of progress, and the need to keep moving (not necessarily the same as keep on walking). A boat is ‘clutched in the hands of a drowned farmer’ but shakes them off, ending up in Davy Jones’ Locker.

‘Journey’s End’ shows the sea’s indifference, characterised as ‘a pagan goddess, always hungry’. Absolution for what we have done is not on offer. In ‘Sound Barrier’religion appears to be questioned, while in ‘Spite’ the sea is ‘shrieking revenge’, for what the poet is too tactful to say. This poem finishes

until even the tide begins to tire

its voice grown hoarse its memory uncertain

In ‘What It’s About’ Valentine resists the temptation to tell the reader, letting her images do their own work.

In Section II, ‘Like Tolstoy’addresses the subject of how we prepare for, or anticipate, our death, starting

Not in hospital; nobody wants that.

A railway station is offered as a better option than a hospice or at home; stanza two is a meditation on various stations before offering Ljubljana as the best station to die in. Duly noted. Stanza three appears to be the poet addressing her private self, offering

the sound of trains

leaving for cities you can dream about

in your last minutes,

There are worse ways to go. ‘Cobalt Variations’ is a meditation on grief and loss, while ‘Alabaster’ offers something similar thematically, but in sonnet form, its last line reading ‘She sat beside him and he fell asleep.’ ‘Afterwards’ follows on, a funeral service then cremation, then what? It finishes

and you went back to work

as if everything had happened

but it made no difference

Appropriately this poem is unpunctuated with spacings and indentations doing the work, and no full stop at the end. Valentine has the knowledge, life experience, and craft skills to handle this material in ways that younger poets may not be able to manage.

Section III moves into a different sort of politics, starting with ‘Commander in Chief’which shows that the sonnet form is up to the task of portraying a zealot who knows he is right, and is justified in not knowing ‘the error of doubt.’ And as for politicians,

They’ll atone

for their treachery later.’ He watches as houses burn,

as hospitals with their load of the limbless rot.

No need to name this man, or say where he carries out these atrocities. In ‘Hostile Environment’ – a phrase used by the Home Office as a way of signalling that British politicians seems to have no regard for international law and apparently feel no compassion towards refugees – we find that

The tigers wait outside the villages.

The crocodiles wait below the water-lilies.

I’ve waited twenty years for permission to live here.

Surely, you say, we don’t have tigers or crocodiles in Britain? Didn’t Theresa May, in 2013, and Priti Patel, in 2021, say that EU citizens who had not applied for ‘settled status’ by the deadline would encounter problems? This poem, of course, could be set in a variety of locations; does Britain have ‘soldiers who wait tetchily by the border’ or a ‘dictator’? Stanza 4 of this sonnet ends

I am waiting for the bank to withhold my money

while the final line is

I am waiting for you to decide to send me back.

Back to where? Presumably somewhere this person would be in danger.

Section IV is ‘A Grenfell Alphabet’, 24 stanzas, one for each floor of Grenfell Tower, originally published as the poet’s contribution to the Grenfell Tower Fund. If this piece isn’t on the GCSE or ‘A’ Level syllabus, it should be. Each stanza forms part of a sustained litany of the things and possessions destroyed by the inferno. So many ordinary things yet all special. Floor 24 reads

X the unknown number of the victims.

Y the question nobody wants to answer.

Z for the zero that is Grenfell Tower

now, its missing windows and scorched stairs,

zero the objects that can still be salvaged,

zero the rooms it would be safe to enter.

Zeus, Zoroaster,

in the zenith above the charred black tower, who welcomed

the singing souls that rose out of the flames?

Indeed. Would anyone be surprised to learn that, four years on, some of the surviving families have still not been re-housed? A lot of money has of course been raised, and distributed by the various charities involved.

Section V, ‘Lethe’, concerns itself with memory, forgetting and how we remember people or events. It tells how someone, as in ‘Not Like This’, could be ‘lost in his own known streets’.‘Before We Knew’ starts ‘As if the sea had given up on change’, before revealing in the second stanza that ‘I’d lost him already. Or rather I was bored.’ The poem finishes

All the destruction had already happened.

Section VI opens with ‘Tidal’, one of several sonnets in the book. This is another watery poem addressed to a reader who is exhorted to

Stay

still, stay silent, listen to the words

the tide brings in on its sweep from the Antarctic,

This could be read as mindfulness in action. The book’s title poem, ‘If You Want Thunder’, is also a sonnet, but more apparently personal, although Valentine is not a noticeably ‘confessional’ poet. Indeed there is a lot of obliquity (in the positive sense of this term) in her work, and all the better for it. This poem refers to

blood dripping from out of you, the man who swore

it wouldn’t hurt, and hurt you, Just because

you could tell no-one (shame) you can’t say now

where you have been or why.

Your reviewer suspects that these lines will resonate with any women reading them. The poem’s final line is

If you want thunder you must learn to talk.

Women will not be silenced, dispossessed, or marginalised. ‘One Day the Poets Will Return to Earth’ echoes W.H. Auden’s elegy ‘ In Memory of W.B.Yeats’ where in Section II, we find this

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its saying where executives

Would never want to tamper;

(W.H.Auden, Selected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson, (Faber & Faber, 1979)

It starts, in a run-on from the title,

and sit on a park bench

with sealed eyes

to let the unstable sun

burn off their fever

and that appears to be their experience of reincarnation; things happen in this poem, but not apparently by the poets’ agency. ‘Sonnet Written with a Pink Pen’ starts by referencing Puccini’s La Boheme, with the aria ‘Che gelida manina’ altered slightly to

My tiny hand is frozen, having cleaned

mould out of the fridge.

The note to this poem shows that there is still some work to do in eliminating stereotypes. The poem gives a flavour of this writers achievements, and concludes

Now that I’ve got this pen, though, I can prove

my feminine vocation: violets, kittens,

cupcakes and curls. Imagine my relief.

I’m not sure any chap would be brave enough to say anything. If You Want Thunder, however, has been brave enough to say all manner of things worth hearing, and both poet and publisher are to be commended for writing and publishing this book; it is anything but ‘same old, same old’. If a poetry of political or social commentary is to be worth reading or hearing, it cannot repeat the tropes of the past, and has to be more than standup comedy with clanky end rhymes. No postcards please.

One or two final observations, although Ruth Valentine is very much a London poet, this book has a strong flavour of the Sussex coast, and not from the occasional day trip to Hastings or thereabouts.

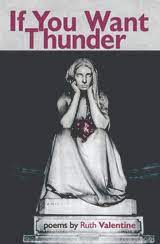

The book is well produced, with no typos in the text noticed, although in the review copy, Section IV was labelled VI. The cover photograph, of a sculpture by Vincenzo Vela, ‘Desolation’ shows the sculpture with a bouquet of flowers in the figure’s lap, making this image an appropriate choice. Now that things might back to ‘normal’ (have I spoken too soon?) there might be a bookshop near you which will stock or order this book.

Nov 30 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Ruth Valentine

What The Thunder Said: Brian Docherty reviews Ruth Valentine’s new collection IF YOU WANT THUNDER

This book, Ruth Valentine’s 10th collection, opens with a sonnet, ‘Past’ where we are told ‘Your task / is keep on walking.’ It’s not clear who the ‘you’ is here; and, whether it is a rhetorical address to the reader, or to someone in particular, this is typical of the book’s procedures, both formally and thematically. It is divided into six sections, and Section 1, ‘Sea-Fret’, starts with ‘Jettisoned’, a bleak, unflinching look at the cost of progress, and the need to keep moving (not necessarily the same as keep on walking). A boat is ‘clutched in the hands of a drowned farmer’ but shakes them off, ending up in Davy Jones’ Locker.

‘Journey’s End’ shows the sea’s indifference, characterised as ‘a pagan goddess, always hungry’. Absolution for what we have done is not on offer. In ‘Sound Barrier’religion appears to be questioned, while in ‘Spite’ the sea is ‘shrieking revenge’, for what the poet is too tactful to say. This poem finishes

until even the tide begins to tire its voice grown hoarse its memory uncertainIn ‘What It’s About’ Valentine resists the temptation to tell the reader, letting her images do their own work.

In Section II, ‘Like Tolstoy’addresses the subject of how we prepare for, or anticipate, our death, starting

A railway station is offered as a better option than a hospice or at home; stanza two is a meditation on various stations before offering Ljubljana as the best station to die in. Duly noted. Stanza three appears to be the poet addressing her private self, offering

the sound of trains leaving for cities you can dream about in your last minutes,There are worse ways to go. ‘Cobalt Variations’ is a meditation on grief and loss, while ‘Alabaster’ offers something similar thematically, but in sonnet form, its last line reading ‘She sat beside him and he fell asleep.’ ‘Afterwards’ follows on, a funeral service then cremation, then what? It finishes

and you went back to work as if everything had happened but it made no differenceAppropriately this poem is unpunctuated with spacings and indentations doing the work, and no full stop at the end. Valentine has the knowledge, life experience, and craft skills to handle this material in ways that younger poets may not be able to manage.

Section III moves into a different sort of politics, starting with ‘Commander in Chief’which shows that the sonnet form is up to the task of portraying a zealot who knows he is right, and is justified in not knowing ‘the error of doubt.’ And as for politicians,

No need to name this man, or say where he carries out these atrocities. In ‘Hostile Environment’ – a phrase used by the Home Office as a way of signalling that British politicians seems to have no regard for international law and apparently feel no compassion towards refugees – we find that

The tigers wait outside the villages. The crocodiles wait below the water-lilies. I’ve waited twenty years for permission to live here.Surely, you say, we don’t have tigers or crocodiles in Britain? Didn’t Theresa May, in 2013, and Priti Patel, in 2021, say that EU citizens who had not applied for ‘settled status’ by the deadline would encounter problems? This poem, of course, could be set in a variety of locations; does Britain have ‘soldiers who wait tetchily by the border’ or a ‘dictator’? Stanza 4 of this sonnet ends

while the final line is

Back to where? Presumably somewhere this person would be in danger.

Section IV is ‘A Grenfell Alphabet’, 24 stanzas, one for each floor of Grenfell Tower, originally published as the poet’s contribution to the Grenfell Tower Fund. If this piece isn’t on the GCSE or ‘A’ Level syllabus, it should be. Each stanza forms part of a sustained litany of the things and possessions destroyed by the inferno. So many ordinary things yet all special. Floor 24 reads

X the unknown number of the victims. Y the question nobody wants to answer. Z for the zero that is Grenfell Tower now, its missing windows and scorched stairs, zero the objects that can still be salvaged, zero the rooms it would be safe to enter. Zeus, Zoroaster, in the zenith above the charred black tower, who welcomed the singing souls that rose out of the flames?Indeed. Would anyone be surprised to learn that, four years on, some of the surviving families have still not been re-housed? A lot of money has of course been raised, and distributed by the various charities involved.

Section V, ‘Lethe’, concerns itself with memory, forgetting and how we remember people or events. It tells how someone, as in ‘Not Like This’, could be ‘lost in his own known streets’.‘Before We Knew’ starts ‘As if the sea had given up on change’, before revealing in the second stanza that ‘I’d lost him already. Or rather I was bored.’ The poem finishes

Section VI opens with ‘Tidal’, one of several sonnets in the book. This is another watery poem addressed to a reader who is exhorted to

Stay still, stay silent, listen to the words the tide brings in on its sweep from the Antarctic,This could be read as mindfulness in action. The book’s title poem, ‘If You Want Thunder’, is also a sonnet, but more apparently personal, although Valentine is not a noticeably ‘confessional’ poet. Indeed there is a lot of obliquity (in the positive sense of this term) in her work, and all the better for it. This poem refers to

blood dripping from out of you, the man who swore it wouldn’t hurt, and hurt you, Just because you could tell no-one (shame) you can’t say now where you have been or why.Your reviewer suspects that these lines will resonate with any women reading them. The poem’s final line is

Women will not be silenced, dispossessed, or marginalised. ‘One Day the Poets Will Return to Earth’ echoes W.H. Auden’s elegy ‘ In Memory of W.B.Yeats’ where in Section II, we find this

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives In the valley of its saying where executives Would never want to tamper; (W.H.Auden, Selected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson, (Faber & Faber, 1979)It starts, in a run-on from the title,

and sit on a park bench with sealed eyes to let the unstable sun burn off their feverand that appears to be their experience of reincarnation; things happen in this poem, but not apparently by the poets’ agency. ‘Sonnet Written with a Pink Pen’ starts by referencing Puccini’s La Boheme, with the aria ‘Che gelida manina’ altered slightly to

My tiny hand is frozen, having cleaned mould out of the fridge.The note to this poem shows that there is still some work to do in eliminating stereotypes. The poem gives a flavour of this writers achievements, and concludes

Now that I’ve got this pen, though, I can prove my feminine vocation: violets, kittens, cupcakes and curls. Imagine my relief.I’m not sure any chap would be brave enough to say anything. If You Want Thunder, however, has been brave enough to say all manner of things worth hearing, and both poet and publisher are to be commended for writing and publishing this book; it is anything but ‘same old, same old’. If a poetry of political or social commentary is to be worth reading or hearing, it cannot repeat the tropes of the past, and has to be more than standup comedy with clanky end rhymes. No postcards please.

One or two final observations, although Ruth Valentine is very much a London poet, this book has a strong flavour of the Sussex coast, and not from the occasional day trip to Hastings or thereabouts.

The book is well produced, with no typos in the text noticed, although in the review copy, Section IV was labelled VI. The cover photograph, of a sculpture by Vincenzo Vela, ‘Desolation’ shows the sculpture with a bouquet of flowers in the figure’s lap, making this image an appropriate choice. Now that things might back to ‘normal’ (have I spoken too soon?) there might be a bookshop near you which will stock or order this book.