Haunts and hauntings: Tanya Parker reviews Mark Mansfield’s Greygolden

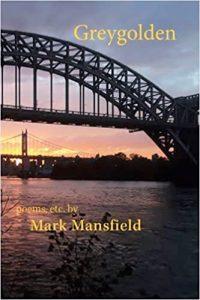

Greygolden

Mark Mansfield

Chester River Press USA 2021

ISBN 9798526192187;

pp 56 $15

Greygolden

Mark Mansfield

Chester River Press USA 2021

ISBN 9798526192187;

pp 56 $15

After the life-changing, culture-altering experiences of the last year, it is difficult not to see every recent artistic offering as a reflection of Covid-19. In this new collection, as in his earlier collection Strangers Like You, Mark Mansfield shows his love for jazz, blues and the cityscapes of the United States. In this new volume, his tone is more personal and his map wider. Unrequited love, passion and early family life are placed between poems inspired by song lyrics and quotations, giving an overall atmosphere of wistful regret, of ‘the road not taken.’ Covid constraints have lent us a suspended atmosphere in which the past can become more real than the present. Mansfield reflects this as he takes us on a detailed journey through his own life.

The twist of the of the opening poem, “Lost Days”, (an English sonnet dedicated to his aunt Dot) is that it manages to be the most vivid of all the pieces, while Mansfield’s first memories of the world are distinctly un-visual:

Your soft Kentucky drawl helped me unblur

our house on Parrish back when I was two,

when I saw by sound and smell, but mostly touch,

and thought my vision how things really were..

And while the scenes are governed by in an English sonnet rhyme-scheme, the author’s early mispronunciation of his uncle’s name (“Dim” for Jim) fractures those imposed rules, being both cute and subversive.

There are few things more symbolic of American rural life than the porch swing. A conduit for memories, it is a cradle at the beginning and end of life. In the final lines of “Lost Days”, the adult Mansfield calls to his aunt to ‘rest a spell, and maybe read this poem / out on the porch swing some summer day’, while in “The Swing” he remembers sitting on the high school swing with his girlfriend. When it reaches its apex, the sweethearts launch themselves onto the grass, leaving the empty seat behind. You must leave the securities of the past behind, he suggests, before you can make any discoveries.

Each figure he remembers takes his/her place as muse and guide, guiding him through part of his journey but ultimately leaving him to continue alone. Perhaps they are his ‘shorelamps,’, (the original title of the collection) or perhaps the lamps are the poems themselves. There is a searching, yearning quality in this volume, (however formal the verse) clearer here than in his earlier work. This is hardly surprising given the new world we are navigating. Every stopping-place – be it a skyscraper, a busy street, even a bed – shows us a fragment of his story before we, like him, must move on.

For Mansfield, landmarks are meeting points and portals. A Central Park fountain, Grant’s Tomb, the Washington Bridge – these are places where loved ones from his past or present may find him, or he them. Walking past the Bethesda Angel fountain on Central Park as a young man, he finds himself alone among a ‘wedge of mostly couples’. Returning to the same spot as an older man, he ‘searches lookalikes’ as he waits for ‘one otherwise engaged’, a loved one who will not return. The spirit of these poems is that of a well-loved play: it can be re-enacted, but never repeated exactly. No performance, even with the same cast, is ever the same twice.

Mansfield’s subtlest examination of inexorable change is a pair of sonnets, “The Grand Hotel (1) and (2)”. In the first, two lovers acting in a play escape from the world of tourist sights and crowds to focus on each other. In the second, the world around them breaks down ‘like a disintegrating roll of film’ and it is their lives they want to escape from in order to get back to the structured certainty of the play.

Shadows, derelict ships, snatches of song, memories of lovers – Greygolden seems to me a ‘remembrance of things past’- a study of those moments when talismans or familiars (a crow, a bar, a bench, a swing) transport the poet to his earlier life. There are lighter moments, not least “Aubade: for Her (and Hermes)” – a 21st century take on Donne’s “The Good Morrow”, perhaps? – but on the whole this is a poet using our Covid-pause to make an honest, if fragmented, record of his history and personal beliefs before reality begins again.

Sep 5 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Mark Mansfield

Haunts and hauntings: Tanya Parker reviews Mark Mansfield’s Greygolden

After the life-changing, culture-altering experiences of the last year, it is difficult not to see every recent artistic offering as a reflection of Covid-19. In this new collection, as in his earlier collection Strangers Like You, Mark Mansfield shows his love for jazz, blues and the cityscapes of the United States. In this new volume, his tone is more personal and his map wider. Unrequited love, passion and early family life are placed between poems inspired by song lyrics and quotations, giving an overall atmosphere of wistful regret, of ‘the road not taken.’ Covid constraints have lent us a suspended atmosphere in which the past can become more real than the present. Mansfield reflects this as he takes us on a detailed journey through his own life.

The twist of the of the opening poem, “Lost Days”, (an English sonnet dedicated to his aunt Dot) is that it manages to be the most vivid of all the pieces, while Mansfield’s first memories of the world are distinctly un-visual:

And while the scenes are governed by in an English sonnet rhyme-scheme, the author’s early mispronunciation of his uncle’s name (“Dim” for Jim) fractures those imposed rules, being both cute and subversive.

There are few things more symbolic of American rural life than the porch swing. A conduit for memories, it is a cradle at the beginning and end of life. In the final lines of “Lost Days”, the adult Mansfield calls to his aunt to ‘rest a spell, and maybe read this poem / out on the porch swing some summer day’, while in “The Swing” he remembers sitting on the high school swing with his girlfriend. When it reaches its apex, the sweethearts launch themselves onto the grass, leaving the empty seat behind. You must leave the securities of the past behind, he suggests, before you can make any discoveries.

Each figure he remembers takes his/her place as muse and guide, guiding him through part of his journey but ultimately leaving him to continue alone. Perhaps they are his ‘shorelamps,’, (the original title of the collection) or perhaps the lamps are the poems themselves. There is a searching, yearning quality in this volume, (however formal the verse) clearer here than in his earlier work. This is hardly surprising given the new world we are navigating. Every stopping-place – be it a skyscraper, a busy street, even a bed – shows us a fragment of his story before we, like him, must move on.

For Mansfield, landmarks are meeting points and portals. A Central Park fountain, Grant’s Tomb, the Washington Bridge – these are places where loved ones from his past or present may find him, or he them. Walking past the Bethesda Angel fountain on Central Park as a young man, he finds himself alone among a ‘wedge of mostly couples’. Returning to the same spot as an older man, he ‘searches lookalikes’ as he waits for ‘one otherwise engaged’, a loved one who will not return. The spirit of these poems is that of a well-loved play: it can be re-enacted, but never repeated exactly. No performance, even with the same cast, is ever the same twice.

Mansfield’s subtlest examination of inexorable change is a pair of sonnets, “The Grand Hotel (1) and (2)”. In the first, two lovers acting in a play escape from the world of tourist sights and crowds to focus on each other. In the second, the world around them breaks down ‘like a disintegrating roll of film’ and it is their lives they want to escape from in order to get back to the structured certainty of the play.

Shadows, derelict ships, snatches of song, memories of lovers – Greygolden seems to me a ‘remembrance of things past’- a study of those moments when talismans or familiars (a crow, a bar, a bench, a swing) transport the poet to his earlier life. There are lighter moments, not least “Aubade: for Her (and Hermes)” – a 21st century take on Donne’s “The Good Morrow”, perhaps? – but on the whole this is a poet using our Covid-pause to make an honest, if fragmented, record of his history and personal beliefs before reality begins again.