Stephen Claughton is transported by Wendy Holborow’s atmospheric poems from India and Africa

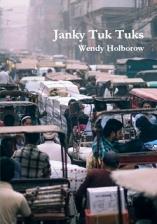

Janky Tuk Tuks

Wendy Holborow

The High Window

ISBN 978-0-244-39812-5

£10.00

Janky Tuk Tuks

Wendy Holborow

The High Window

ISBN 978-0-244-39812-5

£10.00

Wendy Holborow is a prize-winning poet, playwright and short-story writer, who has published poetry collections on subjects as various as living on Corfu, travelling in Italy, the people and animals in Ford Madox Brown’s painting, “Work”, and classics of the European cinema. Her latest, Janky Tuk Tuks, contains poems about India and Africa, as well as a short story set in Africa.

Janky tuk-tuks are clapped-out, motorised rickshaws and hers transport us right into the sights and sounds, not to mention the feel, of India. As she says in “Gradations”, the first poem in the book:

air travel violently tears us out of the cold

hurtles us, say, into the blaze of the tropics

unaccustomed to the torture of scorching heat.

In the next poem, “Haze”, she leaves a ‘drab and grey Port Talbot’ to ‘wake to the vibrancy of India’, though it is only ‘as we drive to pastoral hamlets away from polluted air’ that she finds:

Unsullied skies, freckled shade sweeps the windows’ heat

as we reach that solunar time, dusk falls like ripening wheat.

Contrasts are made between home and abroad, with their different meteorological and emotional climates, and also between the poet’s life and that of the local women; but the poems are mainly concerned with describing what the writer sees. “Through a Lens” is about photographing – and being photographed by and with – people in India as a way of forging connections. In much of the book Holborow is a camera. The images may be linguistically enhanced, but she takes her subjects on their own terms (‘They have their own agenda / these birds we watch / have no awareness that we are charmed / by their presence.’)

A particular feature of her poems is the way in which she heightens an otherwise conversational style with alliteration and assonance, as at the end of “Monsoon”:

In the morning margin of sky

a blush dawn bursts on the warmth

of swarming-insect buzz

wild boars wallow in accumulated mud

but the onslaught of floods is feared

Holborow also makes the use of striking images and unusual words: a tiger with ‘chiaroscuro stripes’ stalks deer with ‘coats like peeling bark’; ‘the Nile startles through trees’; ‘sheets scream damp’; dogs ‘congregate with insincere threats.’ There are ‘pencil line horizons’, ‘humidity as high as the tallest tree’, ‘a journey of giraffes’ and ‘a dazzle of zebras’ – a reference perhaps to the ‘dazzle camouflage’ used on ships in the First World War. There are words such as ‘feculent’, ‘nielloed’, ‘suthering’, ‘crizzling’, ‘smeuse’, ‘lutulent’ and ‘solunar’ – twice (its dictionary definition is ‘due to the conjunction of sun and moon’ and describes a theory predicting the periods of greatest animal activity, although here it seems to mean simply ‘twilit’).

Though I never felt that the lusher language was overdone, there were a few occasions when I thought the plainer style became a little too plain – for instance, in “The Taj Mahal”, the comparative flatness of ‘a paradise garden cultivated by Shah Jahan / for his much loved wife, Mumtaz Mahal who left him bereft’ marred for me an otherwise fine poem (it’s in the shape of a dome) and one or two of the poems (“The Train” or “Tiger”, for example) were rounded off in a way that I didn’t feel did them full justice.

But these are minor criticisms. If there is a problem with descriptive poems in knowing not so much when as how to stop, it’s one she deftly resolves in “Birds”, which ends:

I could describe how the colours of birds

saturate into a saffron sunset

as the sun slips away from a tie-dyed sky

and how they retreat

into their own secret world

incurious oblivious.

By suggesting that there is more she could say about the birds, she keeps the poem airborne.

A number of poems use ‘open field’ composition to good effect. In this context, it conveyed for me the impression of a vibrant, seemingly chaotic world establishing its own order without the imposed constraints of punctuation or metrics. But she also puts it to more specific use, as in “Hanuman” (about a Hindu god), where thought and action are presented simultaneously in:

The child, Hanuman, observed the red orb of the sun

reached toward it

supposing it a piece of fruit

and the subsequent act of recovering his remains is expressed concretely in:

they gathered

his ashes & bones

from the land & the seas.

Sometimes, however, the technique becomes little more than a mannerism – I didn’t feel there was much gained by placing words such as ‘fell’ or ‘up’ and ‘over’ respectively below or above the line.

Holborow handles humour well. “The Highway Code of India”, where the janky tuk-tuks make their appearance, along with ‘rollicking rickshaws’, presents a selection of articles (‘Article 1: The assumption of immortality is required of all road users’ or ‘Article 12: The 10th incarnation of God was an articulated tanker’), illustrated by the accompanying poems. “Doing a Prince Charles” (two sonnets with a decidedly sprung rhythm) describes the potentially harmful effects of Western do-goodery, while “Feed Me to the Tiger” asks that in the event of her death in India, ‘say, in a traffic accident’, the poet’s body should be fed to the tigers of Ranthambore, saving not only on funeral fees and grave maintenance, but also so that: ‘generations to come would talk of their ancestor / devoured by a tiger in Ranthambore.’

The same self-mocking tendency to indulge in personal myth-making is continued in “Not Such a Clanky Jeep” (clanky jeeps being the African equivalent of janky tuk-tuks), in which she describes a jeep getting stuck in a ‘National Park / patrolled only by ferocious creatures’. Her instinct is to embellish the tale with stories of being menaced by lions, a leopard and a herd of elephants – amusing in retrospect, but after their driver refuses to get out to winch the vehicle to safety and manages instead to manoeuvre it out of the mud, the fears become more real. They travel on ‘in exultation / yet not knowing / if a deeper morass awaits / or the imagined elephants loiter / around the next bend.’

In “Twelve Ugandan Women”, she says that her most memorable moment was not an encounter with animals, but being photographed with a group of brightly-dressed women who insisted on shaking her hand. Nevertheless, her animals are vividly described. There is rage against cruelty in “Dead Horses”, one of them sunk into the sand ‘like the carcass of a wrecked ship’, as well as poems featuring chimps, monkeys, giraffes, zebras and lions, and the gloriously-titled “Glamping with Hippos”.

The very fine short story, “Ngozi”, with which the book ends is about an African woman, alone with her four young children, beginning a journey from their looted village to what she hopes will be the safety of a refugee camp. Told simply in short sentences, it nevertheless creates an atmosphere that draws us fully into the woman’s world and the terrible predicament she faces.

Taking his cue from the title of one of the poems, Professor John Goodby says in his introduction that the book ‘contains a “fabulous rabble” of rattling good poems’. That is certainly true, as is his observation that they relish language for its own sake. I don’t care if the dictionary tells me that ‘janky’ is Afro-American slang, not Indian as I had assumed, or that ‘tuk-tuk’ is a Thai word – Wendy Holborow’s arresting fusion is the perfect phrase for these unruly, mechanical beasts.

Apr 5 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Wendy Holborow

Stephen Claughton is transported by Wendy Holborow’s atmospheric poems from India and Africa

Wendy Holborow is a prize-winning poet, playwright and short-story writer, who has published poetry collections on subjects as various as living on Corfu, travelling in Italy, the people and animals in Ford Madox Brown’s painting, “Work”, and classics of the European cinema. Her latest, Janky Tuk Tuks, contains poems about India and Africa, as well as a short story set in Africa.

Janky tuk-tuks are clapped-out, motorised rickshaws and hers transport us right into the sights and sounds, not to mention the feel, of India. As she says in “Gradations”, the first poem in the book:

In the next poem, “Haze”, she leaves a ‘drab and grey Port Talbot’ to ‘wake to the vibrancy of India’, though it is only ‘as we drive to pastoral hamlets away from polluted air’ that she finds:

Contrasts are made between home and abroad, with their different meteorological and emotional climates, and also between the poet’s life and that of the local women; but the poems are mainly concerned with describing what the writer sees. “Through a Lens” is about photographing – and being photographed by and with – people in India as a way of forging connections. In much of the book Holborow is a camera. The images may be linguistically enhanced, but she takes her subjects on their own terms (‘They have their own agenda / these birds we watch / have no awareness that we are charmed / by their presence.’)

A particular feature of her poems is the way in which she heightens an otherwise conversational style with alliteration and assonance, as at the end of “Monsoon”:

In the morning margin of sky a blush dawn bursts on the warmth of swarming-insect buzz wild boars wallow in accumulated mud but the onslaught of floods is fearedHolborow also makes the use of striking images and unusual words: a tiger with ‘chiaroscuro stripes’ stalks deer with ‘coats like peeling bark’; ‘the Nile startles through trees’; ‘sheets scream damp’; dogs ‘congregate with insincere threats.’ There are ‘pencil line horizons’, ‘humidity as high as the tallest tree’, ‘a journey of giraffes’ and ‘a dazzle of zebras’ – a reference perhaps to the ‘dazzle camouflage’ used on ships in the First World War. There are words such as ‘feculent’, ‘nielloed’, ‘suthering’, ‘crizzling’, ‘smeuse’, ‘lutulent’ and ‘solunar’ – twice (its dictionary definition is ‘due to the conjunction of sun and moon’ and describes a theory predicting the periods of greatest animal activity, although here it seems to mean simply ‘twilit’).

Though I never felt that the lusher language was overdone, there were a few occasions when I thought the plainer style became a little too plain – for instance, in “The Taj Mahal”, the comparative flatness of ‘a paradise garden cultivated by Shah Jahan / for his much loved wife, Mumtaz Mahal who left him bereft’ marred for me an otherwise fine poem (it’s in the shape of a dome) and one or two of the poems (“The Train” or “Tiger”, for example) were rounded off in a way that I didn’t feel did them full justice.

But these are minor criticisms. If there is a problem with descriptive poems in knowing not so much when as how to stop, it’s one she deftly resolves in “Birds”, which ends:

By suggesting that there is more she could say about the birds, she keeps the poem airborne.

A number of poems use ‘open field’ composition to good effect. In this context, it conveyed for me the impression of a vibrant, seemingly chaotic world establishing its own order without the imposed constraints of punctuation or metrics. But she also puts it to more specific use, as in “Hanuman” (about a Hindu god), where thought and action are presented simultaneously in:

and the subsequent act of recovering his remains is expressed concretely in:

Sometimes, however, the technique becomes little more than a mannerism – I didn’t feel there was much gained by placing words such as ‘fell’ or ‘up’ and ‘over’ respectively below or above the line.

Holborow handles humour well. “The Highway Code of India”, where the janky tuk-tuks make their appearance, along with ‘rollicking rickshaws’, presents a selection of articles (‘Article 1: The assumption of immortality is required of all road users’ or ‘Article 12: The 10th incarnation of God was an articulated tanker’), illustrated by the accompanying poems. “Doing a Prince Charles” (two sonnets with a decidedly sprung rhythm) describes the potentially harmful effects of Western do-goodery, while “Feed Me to the Tiger” asks that in the event of her death in India, ‘say, in a traffic accident’, the poet’s body should be fed to the tigers of Ranthambore, saving not only on funeral fees and grave maintenance, but also so that: ‘generations to come would talk of their ancestor / devoured by a tiger in Ranthambore.’

The same self-mocking tendency to indulge in personal myth-making is continued in “Not Such a Clanky Jeep” (clanky jeeps being the African equivalent of janky tuk-tuks), in which she describes a jeep getting stuck in a ‘National Park / patrolled only by ferocious creatures’. Her instinct is to embellish the tale with stories of being menaced by lions, a leopard and a herd of elephants – amusing in retrospect, but after their driver refuses to get out to winch the vehicle to safety and manages instead to manoeuvre it out of the mud, the fears become more real. They travel on ‘in exultation / yet not knowing / if a deeper morass awaits / or the imagined elephants loiter / around the next bend.’

In “Twelve Ugandan Women”, she says that her most memorable moment was not an encounter with animals, but being photographed with a group of brightly-dressed women who insisted on shaking her hand. Nevertheless, her animals are vividly described. There is rage against cruelty in “Dead Horses”, one of them sunk into the sand ‘like the carcass of a wrecked ship’, as well as poems featuring chimps, monkeys, giraffes, zebras and lions, and the gloriously-titled “Glamping with Hippos”.

The very fine short story, “Ngozi”, with which the book ends is about an African woman, alone with her four young children, beginning a journey from their looted village to what she hopes will be the safety of a refugee camp. Told simply in short sentences, it nevertheless creates an atmosphere that draws us fully into the woman’s world and the terrible predicament she faces.

Taking his cue from the title of one of the poems, Professor John Goodby says in his introduction that the book ‘contains a “fabulous rabble” of rattling good poems’. That is certainly true, as is his observation that they relish language for its own sake. I don’t care if the dictionary tells me that ‘janky’ is Afro-American slang, not Indian as I had assumed, or that ‘tuk-tuk’ is a Thai word – Wendy Holborow’s arresting fusion is the perfect phrase for these unruly, mechanical beasts.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, travel, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Stephen Claughton, travel