‘The American Clock: A Vaudeville’

by Arthur Miller.

Directed by Rachel Chavkin.

The Old Vic 4th February – 30th March

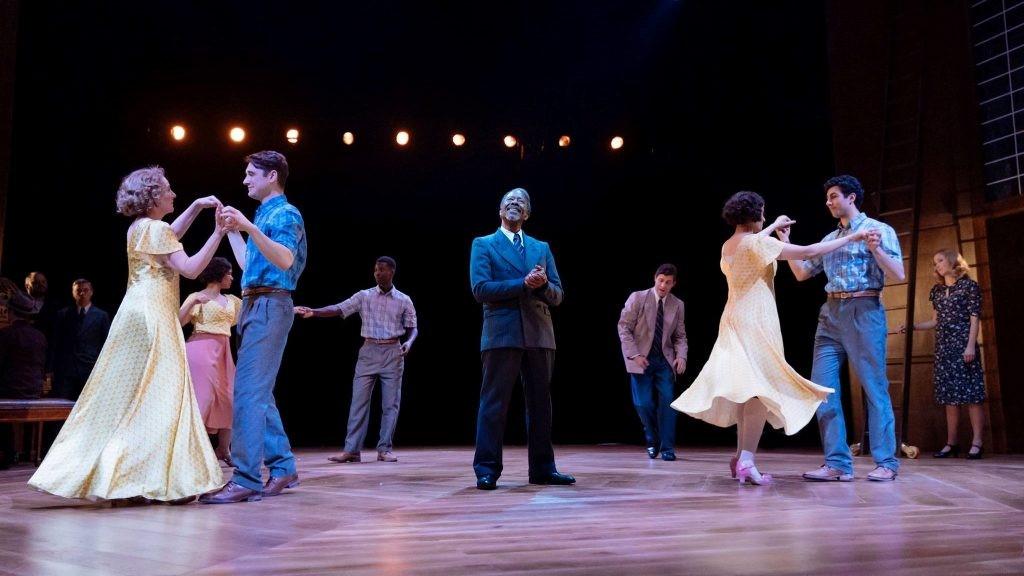

Of all the Miller revivals currently doing the capital’s round, ‘The American Clock’ is not the softest option for any director, actor or audience to take on. Part social documentary, part human drama, part political commentary, it can feel at times like it has bitten off more vision and message than it can theatrically deliver. Nothing daunted, Rachel Chavkin has decided to take the lumbering bull by its socialist horns and, with a nod in the direction of Peter Wood and his acclaimed 1986 NT production, opted for the energetic, jazzed-up ‘vaudeville’ version of the play, here complete with revolving stage, sharply choreographed song and dance numbers and an onstage band. A series of interlinked tableaux presenting a variety of characters reeling from the effects of the ’29 Crash and The Great Depression is punctuated by musical interludes featuring songs of the period, often juxtaposed with modern, bassy beats.

On the whole, it works; at times brilliantly (Golda Rosheuval’s bluesy vocals and Ewan Wardrop’s tap-dancing corporate executive spring to mind) confirming suspicions that the script plays better than it reads. Miller’s human panorama and heartfelt message – at its core, the inhumanity of the Capitalist System and its innate potential to destroy itself and those who play by its compassionless rules – are never allowed to congeal into heavyweight stodge nor deviate satirically into Busby Berkeley Does the Wall Street Crash. The music and movement are high quality and bear more than a passing relevance to the themes (which are powerful and plentiful) and the narrative (which is thin and patchy; not really the point of this piece) while the upbeat, kinaesthetic format lends an accessibility and coherence to the material which it would otherwise lack.

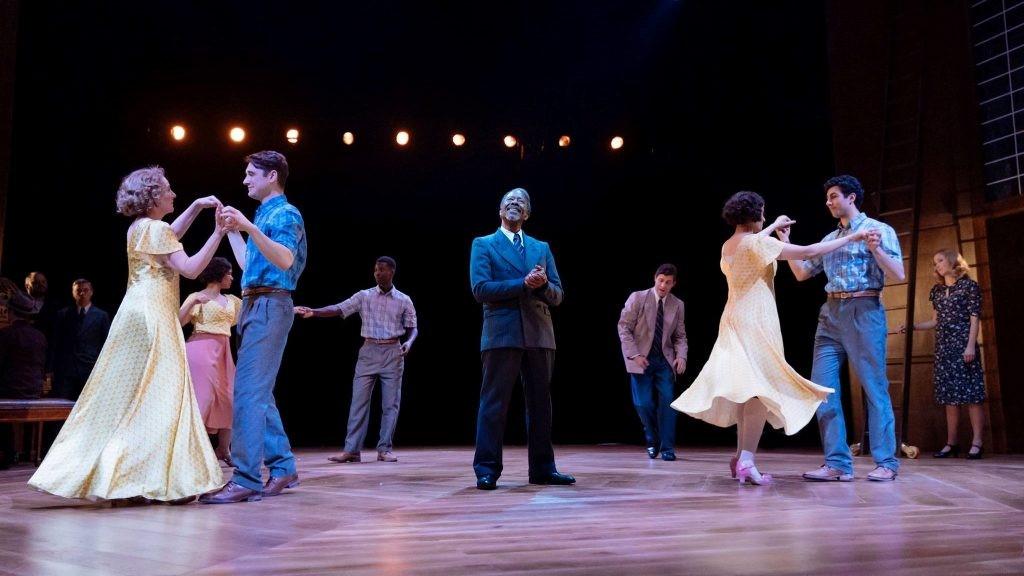

Further binding factors are the magisterial Grand Narrator presence of Arthur Robertson (a gravelly-voiced Morgan Freeman-like Clarke Peters) who opens and closes the show and introduces and comments on many of the scenes; the Baum family, our focus characters, who descend from comfortable, servant-supported middle-class affluence to cramped, mortgage debt collector-fearing penury (rather like Miller himself); most importantly, how the spectre of an unexpected fall from financial grace will pay no heed to class, family or wealth, and can affect everybody from a Wall Street mega-broker to a plain honest Midwest farmer. Only Mr Robertson escapes: prescient enough to see The Crash coming, he cashes in his investments before things turn bad and makes more money during the Hungry 30s than he has ever done before. Huh. There’s always one.

Strangely enough, given that much of the play’s content is based on Miller’s memories of his New York adolescence and the moving personal accounts of The Great Depression recorded in Studs Terkel’s ‘Hard Times’, it is the human side of the story which does not quite gel and convince. Miller has always had the ability to sum up an entire attitude, generation or sector of society in a line or two of dialogue which avoids either the vacuity of aphorism or the narrowness of mundanity. Yet here, characters vacillate uneasily between Individuals you want to invest in emotionally, and Types whose situation carries a message you want (or feel you need) to understand. Intellectually, you can buy this angle. Types are not bound by the context in which they are presented, so can achieve wider relevance in meaning and message than Individuals unravelling their poignant human story in a kind of thoughtfully constructed, socially-sensitive soap opera. In terms of connection and empathy, however, it’s a harder sell.

The same thinking applies to the production’s dramatic configuration of characters and their roles. The Baum Family, which spans three generations and includes cousins, aunts, uncles and in-laws, is our focal point in a narrative sequence which frequently jumps in time and space. Various members appear and overlap in a kaleidoscope of related but contrasting situations as they gradually age in the course of the play, but character continuity and recognition are compromised further by having the three core roles (Moe the Dad, Rose the Mom and Lee the Son) played by three different sets of three actors who travel the ethnic spectrum from White to Asian to Black. Each also plays one or more other, different roles. (Hang on a minute – wasn’t he Lee’s dad? And now he’s a sheriff in a bar in the Deep South?). One effect of this deliberate mechanism of alienation is the separation of actor from character and role. We’re back to Types and Universality, and the championing of message over messenger. Another potential effect is audience confusion and distraction caused by the very superficial inconsistency they are meant to see through and rise above.

So to the ending. ‘The American Clock’ is a play about belief: the erosion of old, familiar, long-held beliefs and the desperate, humanly needful search for something to replace them. Lee Baum, accused by his father of not believing in anything, is attracted to Marxism, a philosophy with which he cannot find fault but cannot commit to, because it lacks a natural and sympathetic understanding of the mentality of the white working class. What he does believe by the end is that there is a ‘system’ which controls his life. Yet the ending is upbeat. Arthur Robertson is left to deliver Miller’s final word. What saved the country; the net (and possibly unintended) result of Roosevelt and his New Deal was that “the people came to believe that the country actually belonged to them.” Really? Could this sound a little hollow or contrived after a three-hour procession of characters in the grip of a system beyond their control; corporate financiers who shoot themselves in executive washrooms; men too proud to stave off starvation by going onto welfare; families living in fear of debt collectors; land repossessed and auctioned for a song to pay off loans; the rise of extremist politics? They ended up believing the country belonged to them? Well, good – who else would want it?

Gary Beahan © 2019.

‘The American Clock’ plays at The Old Vic 4th February – 30th March

‘The American Clock: A Vaudeville’

by Arthur Miller.

Directed by Rachel Chavkin.

The Old Vic 4th February – 30th March

Of all the Miller revivals currently doing the capital’s round, ‘The American Clock’ is not the softest option for any director, actor or audience to take on. Part social documentary, part human drama, part political commentary, it can feel at times like it has bitten off more vision and message than it can theatrically deliver. Nothing daunted, Rachel Chavkin has decided to take the lumbering bull by its socialist horns and, with a nod in the direction of Peter Wood and his acclaimed 1986 NT production, opted for the energetic, jazzed-up ‘vaudeville’ version of the play, here complete with revolving stage, sharply choreographed song and dance numbers and an onstage band. A series of interlinked tableaux presenting a variety of characters reeling from the effects of the ’29 Crash and The Great Depression is punctuated by musical interludes featuring songs of the period, often juxtaposed with modern, bassy beats.

On the whole, it works; at times brilliantly (Golda Rosheuval’s bluesy vocals and Ewan Wardrop’s tap-dancing corporate executive spring to mind) confirming suspicions that the script plays better than it reads. Miller’s human panorama and heartfelt message – at its core, the inhumanity of the Capitalist System and its innate potential to destroy itself and those who play by its compassionless rules – are never allowed to congeal into heavyweight stodge nor deviate satirically into Busby Berkeley Does the Wall Street Crash. The music and movement are high quality and bear more than a passing relevance to the themes (which are powerful and plentiful) and the narrative (which is thin and patchy; not really the point of this piece) while the upbeat, kinaesthetic format lends an accessibility and coherence to the material which it would otherwise lack.

Further binding factors are the magisterial Grand Narrator presence of Arthur Robertson (a gravelly-voiced Morgan Freeman-like Clarke Peters) who opens and closes the show and introduces and comments on many of the scenes; the Baum family, our focus characters, who descend from comfortable, servant-supported middle-class affluence to cramped, mortgage debt collector-fearing penury (rather like Miller himself); most importantly, how the spectre of an unexpected fall from financial grace will pay no heed to class, family or wealth, and can affect everybody from a Wall Street mega-broker to a plain honest Midwest farmer. Only Mr Robertson escapes: prescient enough to see The Crash coming, he cashes in his investments before things turn bad and makes more money during the Hungry 30s than he has ever done before. Huh. There’s always one.

Strangely enough, given that much of the play’s content is based on Miller’s memories of his New York adolescence and the moving personal accounts of The Great Depression recorded in Studs Terkel’s ‘Hard Times’, it is the human side of the story which does not quite gel and convince. Miller has always had the ability to sum up an entire attitude, generation or sector of society in a line or two of dialogue which avoids either the vacuity of aphorism or the narrowness of mundanity. Yet here, characters vacillate uneasily between Individuals you want to invest in emotionally, and Types whose situation carries a message you want (or feel you need) to understand. Intellectually, you can buy this angle. Types are not bound by the context in which they are presented, so can achieve wider relevance in meaning and message than Individuals unravelling their poignant human story in a kind of thoughtfully constructed, socially-sensitive soap opera. In terms of connection and empathy, however, it’s a harder sell.

The same thinking applies to the production’s dramatic configuration of characters and their roles. The Baum Family, which spans three generations and includes cousins, aunts, uncles and in-laws, is our focal point in a narrative sequence which frequently jumps in time and space. Various members appear and overlap in a kaleidoscope of related but contrasting situations as they gradually age in the course of the play, but character continuity and recognition are compromised further by having the three core roles (Moe the Dad, Rose the Mom and Lee the Son) played by three different sets of three actors who travel the ethnic spectrum from White to Asian to Black. Each also plays one or more other, different roles. (Hang on a minute – wasn’t he Lee’s dad? And now he’s a sheriff in a bar in the Deep South?). One effect of this deliberate mechanism of alienation is the separation of actor from character and role. We’re back to Types and Universality, and the championing of message over messenger. Another potential effect is audience confusion and distraction caused by the very superficial inconsistency they are meant to see through and rise above.

So to the ending. ‘The American Clock’ is a play about belief: the erosion of old, familiar, long-held beliefs and the desperate, humanly needful search for something to replace them. Lee Baum, accused by his father of not believing in anything, is attracted to Marxism, a philosophy with which he cannot find fault but cannot commit to, because it lacks a natural and sympathetic understanding of the mentality of the white working class. What he does believe by the end is that there is a ‘system’ which controls his life. Yet the ending is upbeat. Arthur Robertson is left to deliver Miller’s final word. What saved the country; the net (and possibly unintended) result of Roosevelt and his New Deal was that “the people came to believe that the country actually belonged to them.” Really? Could this sound a little hollow or contrived after a three-hour procession of characters in the grip of a system beyond their control; corporate financiers who shoot themselves in executive washrooms; men too proud to stave off starvation by going onto welfare; families living in fear of debt collectors; land repossessed and auctioned for a song to pay off loans; the rise of extremist politics? They ended up believing the country belonged to them? Well, good – who else would want it?

Gary Beahan © 2019.

‘The American Clock’ plays at The Old Vic 4th February – 30th March