James Roderick Burns raises some questions of balance in relation to Susan Utting’s recent ‘New & Selected’

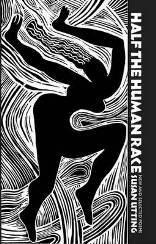

Half the Human Race: New and Selected Poems

Susan Utting

Two Rivers Press

ISBN 978-1-909747-25-8

£9.99

Half the Human Race: New and Selected Poems

Susan Utting

Two Rivers Press

ISBN 978-1-909747-25-8

£9.99

Half the Human Race is notable for two reasons. It is a very unusual ‘selected’, being generous in adding a significant body of new work (41 poems, essentially a new collection); but it feels rather stingy in the selections from previous books (39 in total, with only 11 from Fair’s Fair, the latest collection, published in 2012). This leaves the book feeling unbalanced, more a slightly enhanced new collection than the usual summary of a career to date in which readers new to the poet’s work can see her voice and themes emerge over time. Even reading the selections in chronological order, leaving the new first half of the book to last, it feels rushed, skimpy – a bit stinting. Where a poem succeeds, like ‘Her Bones’ from 2006’s Houses Without Walls (“her bones have thinned to claypipe brittle/till she is a shepherd’s crook, a rusty angle-poise”), we struggle to see it in the broader context of its contemporary work, and are left with a feeling of isolated rather than sustained quality.

And this is the second hallmark of the volume. There are islands of brilliance rising above the waters: ‘The Better the Day’ and ‘Sea View Hotel’, two poems exploring the feelings of Agnes, a scullery maid in a seaside town; ‘The Artist’s Model Daydreams’; ‘Under the Blue Ball’, a pub-riot of a poem reminiscent of Dylan Thomas – “over the road the dead shake their headstones/to Country & Western”). But overall the book feels calm and competent if unexciting, its surface placid, tranquil and mostly undisturbed by moments of originality or daring. The poet has a tendency to rely on well-established conceits – two poems within a page of each other, for instance, ‘Today’s Blue’ and ‘Noise, Delaunay’s Road’, deploy a list of negatives stacked up into a pile before rising to a positive crescendo – and in service of humanising women’s lives, prone to setting up male chauvinist strawmen. The title poem is a case in point, combining both these tendencies:

Say we have tiny, dainty feet …

Say

we’re sweethearts, dolls with waists and hips

that cannot hold our vital organs, say we’re

posable, blow-up generous, bonny, plus-size.

Say nice arse, a lovely pair. Say skin like silk,

like leather; say damaged by the sun.

(‘Half the Human Race’)

While skilfully done, the poem doesn’t acknowledge that nobody would actually say any of this; some limited, uneducated men may think it, and women certainly have had to endure such attitudes, but enumerating them in list form merely undermines the reader’s faith in the poet’s vision, as well as her judgement. This is, after all, the title poem, and in its prominence serves to mask those poems where Utting does a wonderful job of exploring the complexity of women’s lives.

The two Agnes poems, for instance, and ‘The Better the Day’ in particular, are note-perfect. Intercutting short italicised stanzas describing the sea, shore and pier (which “stands firm/against the wash and suck of shingle-water”) with the grinding detail of Agnes’s daily chores, Utting illustrates two great truths of women’s experience, especially that of working class women: there is real escape to be found in the aesthetic (“on a good day/a twinkle of sun”; “the sea reflects the pier,/its scalloped loops of fairy lights”) but like the relentless sea, work and obligation always return. Agnes experiences “the niggling ache in her back” or “angry red hands”, is “at best unnoticed or at least chastised,/cursed for her weariness” far more often than she is able to rest by the shore and take in the view of the waves under the pier.

It is a harsh truth beautifully enhanced by the complimentary poem, ‘Sea View Hotel’:

Both hands

on the scrubbing brush, its wooden back,

she feels the dip of its waisted shape,

jogs the pail to see water ripple a dance,

catch a glimpse of early sun. Her back’s

to the sea but she’s at the end of the pier

with the spangled girls, high-stepping legs in a

fishnet line, kicking their way past the footlights’

beam, plumed heads bobbing to a can-can tune.

There are other, similar moments in the book, but they appear too infrequently and are crowded out by poems which are not so memorable. Perhaps the selection is an attempt to represent a scale of achievement over time, but the way the book is constructed means this gets lost, and the most effective poems – bursting through like Agnes’s epiphanies – seem occasional rather than deliberate, as do excellent aspects of otherwise less striking poems.

Unfortunately, in the words of ‘Hinged Copper Poem Dress’, too often through Half the Human Race “written there, against/the odds, is something like a poem”.

James Roderick Burns raises some questions of balance in relation to Susan Utting’s recent ‘New & Selected’

Half the Human Race is notable for two reasons. It is a very unusual ‘selected’, being generous in adding a significant body of new work (41 poems, essentially a new collection); but it feels rather stingy in the selections from previous books (39 in total, with only 11 from Fair’s Fair, the latest collection, published in 2012). This leaves the book feeling unbalanced, more a slightly enhanced new collection than the usual summary of a career to date in which readers new to the poet’s work can see her voice and themes emerge over time. Even reading the selections in chronological order, leaving the new first half of the book to last, it feels rushed, skimpy – a bit stinting. Where a poem succeeds, like ‘Her Bones’ from 2006’s Houses Without Walls (“her bones have thinned to claypipe brittle/till she is a shepherd’s crook, a rusty angle-poise”), we struggle to see it in the broader context of its contemporary work, and are left with a feeling of isolated rather than sustained quality.

And this is the second hallmark of the volume. There are islands of brilliance rising above the waters: ‘The Better the Day’ and ‘Sea View Hotel’, two poems exploring the feelings of Agnes, a scullery maid in a seaside town; ‘The Artist’s Model Daydreams’; ‘Under the Blue Ball’, a pub-riot of a poem reminiscent of Dylan Thomas – “over the road the dead shake their headstones/to Country & Western”). But overall the book feels calm and competent if unexciting, its surface placid, tranquil and mostly undisturbed by moments of originality or daring. The poet has a tendency to rely on well-established conceits – two poems within a page of each other, for instance, ‘Today’s Blue’ and ‘Noise, Delaunay’s Road’, deploy a list of negatives stacked up into a pile before rising to a positive crescendo – and in service of humanising women’s lives, prone to setting up male chauvinist strawmen. The title poem is a case in point, combining both these tendencies:

While skilfully done, the poem doesn’t acknowledge that nobody would actually say any of this; some limited, uneducated men may think it, and women certainly have had to endure such attitudes, but enumerating them in list form merely undermines the reader’s faith in the poet’s vision, as well as her judgement. This is, after all, the title poem, and in its prominence serves to mask those poems where Utting does a wonderful job of exploring the complexity of women’s lives.

The two Agnes poems, for instance, and ‘The Better the Day’ in particular, are note-perfect. Intercutting short italicised stanzas describing the sea, shore and pier (which “stands firm/against the wash and suck of shingle-water”) with the grinding detail of Agnes’s daily chores, Utting illustrates two great truths of women’s experience, especially that of working class women: there is real escape to be found in the aesthetic (“on a good day/a twinkle of sun”; “the sea reflects the pier,/its scalloped loops of fairy lights”) but like the relentless sea, work and obligation always return. Agnes experiences “the niggling ache in her back” or “angry red hands”, is “at best unnoticed or at least chastised,/cursed for her weariness” far more often than she is able to rest by the shore and take in the view of the waves under the pier.

It is a harsh truth beautifully enhanced by the complimentary poem, ‘Sea View Hotel’:

There are other, similar moments in the book, but they appear too infrequently and are crowded out by poems which are not so memorable. Perhaps the selection is an attempt to represent a scale of achievement over time, but the way the book is constructed means this gets lost, and the most effective poems – bursting through like Agnes’s epiphanies – seem occasional rather than deliberate, as do excellent aspects of otherwise less striking poems.

Unfortunately, in the words of ‘Hinged Copper Poem Dress’, too often through Half the Human Race “written there, against/the odds, is something like a poem”.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, James Roderick Burns, poetry