Thomas Ovans investigates a Shoestring anthology edited by Merryn Williams which has received an unusual amount of attention for a poetry book.

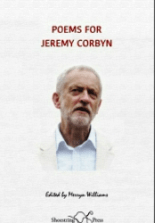

Poems for Jeremy Corbyn

Edited by Merryn Williams

Shoestring Press

ISBN: 978-1-910323-66-3

88 pp £10

Poems for Jeremy Corbyn

Edited by Merryn Williams

Shoestring Press

ISBN: 978-1-910323-66-3

88 pp £10

Even before London Grip has given its opinion, this book has been featured in the national press. Released just in time for the Labour Party conference, it attracted notice in the parts of the papers that other poetry books seldom reach. This moment in the headlines – brief though it was – is a mild encouragement both for poetry in general and also for those who still nurse hopes that Jeremy Corbyn can reshape the Labour Party into an effective opposition and even a party of government.

So what are these ‘Poems for Jeremy Corbyn’? Well, some of them – let’s call them appreciations – pay him gracious compliments. Others might be labelled advocacies because they stand up for him against those who oppose or obstruct him whether in the media or in Westminster. Then again there are those – and these I think are the most interesting – which offer some kind of advice by addressing policies which Corbyn has proposed (or which the poet thinks he should propose).

Among the appreciations, ‘The Socialist’ is one of the most straightforward, being almost a potted poetic biography: He’s fighting for the miners …. He’s at the march in 2003 …. He’s being bullied by his fellow MPs. ‘At the Marquis of Granby’ is more personal and describes a (real or imagined?) pub conversation with Jeremy Corbyn from which it emerges

After thirty-three years tied up in the sack

of the Commons you learn to respond with sublime

indifference to fools.

Several pieces emphasise the appeal of mere difference in a politician – most compactly in ‘Corbyn Haiku’

Jeremy is not

a typical leader – one

reason we love him.

Corbyn-optimism seldom becomes disproportionate however. ‘J.C.’ reaches the conclusion

Corbyn’s no knight in shining vest

or bright Messiah from the West

(he’d say)

but someone who has found a way to voice

a fractured country’s need for choice ...

If praise for its subject is usually quite measured, the anthology gives freer rein to scorn for his various opponents. ‘J.C.’ is also an advocacy poem that laments negative treatment by the media

The practised put-downs, and the usual sneers,

predictable pandering to baser fears

the lazy tricks that served for years.

‘On your unsuitability for high office’ recognizes that press attacks begin as soon as they realise / you might succeed in changing/more than the occasional / light bulb.

As for political opponents, there is withering contempt for David Cameron’s cheap point-scoring at PMQ’s about Corbyn’s dress code in ‘Have with you to Savile Row’. Nor do the posturings of other members of the Tory party go un-noticed: ‘Twas Brexit and the slithy Gove / did frottercrutch in dwarfish glee (‘Stabberjocky’); and a characterisation of the current government’s manifesto as

blind our eyes with Brexit,

pay Boris for his blunders,

Job-Seeker those in wheelchairs,

tell us lies about the Trade Deal plans.

This comes from ‘Tell me lies about the austerity plan’ – which is of course a (well-done) pastiche of Adrian Mitchell’s famous ‘Tell me lies about Vietnam’. It does not limit itself to attacking the Conservatives but – like several other pieces in the anthology – also engages in retrospective criticism of ‘Blairites’ and Tony Blair’s legacy.

Adversaries from Corbyn’s own party are attacked in a more generalised way in ‘The seven ages of a Labour MP’ which run from posing and strutting in the NUS to being sans teeth, sans brain, sans guts, sans principles. ‘Song of the knives-in-the-backbenchers’ (something of a tour de force based on the Bernstein-Sondheim song ‘Gee Officer Krupke’ from West Side Story) has some of Corbyn’s internal opponents protesting

We are pink, we are pink

we’re extremely pink!

Deep inside, some parts of us are pink!

The ‘advice poems’ cover quite a wide range of policy areas. Sympathy for immigrants and the plight of refugees is one of the most common – giving the lie to they come over ‘ere y’know / and get everything via a neat parable on Muntjac deer whose tiny migrant hooves barely dent / the damp ground. ‘Scarlet Macaws’ makes an eloquent plea for diversity, tolerance and freedom from exploitation; while, in contrast, the uncaring pressures of austerity are well captured in ‘Tory Story’:

When she jumped in front of the train

...

She didn’t think of the benefits officer

guilty at what he’d done to fill

his weekly sanctions quota.

All she could see was the month ahead

Empty fridge, rent arrears, the beckoning street,

(This resonates well with the recently released Ken Loach film I, Daniel Blake about the rigidity of the benefit system.)

‘Maiden Speech’ appears to take on the political elite’s blind faith in neo-liberal capitalism; and ‘A Scream in 1890’ reminds us of Victorian factory conditions which current economic theories may be ready to justify all over again. ‘The Anthropocene’ tackles the even grosser blindness to climate change by mocking the feeble refrain how were we to know? Meanwhile ‘The Blame’ skewers a very English problem: Bloody class. The common bloody shame.

These few brief extracts should give an impression that this is a varied and lively selection of poems seeking wholeheartedly to engage with issues that genuinely matter. This is a truthful impression; and yet I could wish the book felt a little less ‘well-behaved’. It is perhaps unfortunate that I recently visited the V & A exhibition You Say You Want a Revolution? and could not help contrasting the extravagant (and, yes, sometimes silly) enthusiasm for change in the 1960s with the more muted and passive responses in the country at large in the face of current causes of discontent. I would have liked to find more pages in this anthology crackling with fire and passion. There are certainly sparks and flashes – not least in the Mitchell and Sondheim pastiche pieces. But these also have an unintended consequence of slightly overshadowing other poems in the book by reminding us what magnificently memorable results can be achieved when fine poets/lyricists turn their imagination and language skills loose on big issues. All that being said, however, this is a book to be welcomed and one to be read and re-read because the poems have a cumulative effect. It should also be seen as a model and an encouragement to other poets and publishers to get some well-crafted rhetoric out into the world of political debate. There have been precious few ‘fine words’ in recent campaigning.

In conclusion, it will perhaps have been noted that I have not mentioned any of the featured poets by name – merely given titles for any quoted poems. An anthology is a cooperative venture and all contributors play some part in the overall impact; hence, as a reviewer, I find I am increasingly reluctant to single out certain authors just because their piece happens to be neatly quotable within my line of critical argument. Such reluctance to name names is oddly intensified in the present special case because I find myself troubled by a cult of personality that seems to have grown up around Jeremy Corbyn himself (and which might be further enhanced by the existence of this collection). In fairness, however, one of the poems in the book (‘Something happened’) does confront this question – and this can have the last word:

They like to pretend

it’s all about him

but it’s not

it’s all about us

Thomas Ovans investigates a Shoestring anthology edited by Merryn Williams which has received an unusual amount of attention for a poetry book.

Even before London Grip has given its opinion, this book has been featured in the national press. Released just in time for the Labour Party conference, it attracted notice in the parts of the papers that other poetry books seldom reach. This moment in the headlines – brief though it was – is a mild encouragement both for poetry in general and also for those who still nurse hopes that Jeremy Corbyn can reshape the Labour Party into an effective opposition and even a party of government.

So what are these ‘Poems for Jeremy Corbyn’? Well, some of them – let’s call them appreciations – pay him gracious compliments. Others might be labelled advocacies because they stand up for him against those who oppose or obstruct him whether in the media or in Westminster. Then again there are those – and these I think are the most interesting – which offer some kind of advice by addressing policies which Corbyn has proposed (or which the poet thinks he should propose).

Among the appreciations, ‘The Socialist’ is one of the most straightforward, being almost a potted poetic biography: He’s fighting for the miners …. He’s at the march in 2003 …. He’s being bullied by his fellow MPs. ‘At the Marquis of Granby’ is more personal and describes a (real or imagined?) pub conversation with Jeremy Corbyn from which it emerges

Several pieces emphasise the appeal of mere difference in a politician – most compactly in ‘Corbyn Haiku’

Corbyn-optimism seldom becomes disproportionate however. ‘J.C.’ reaches the conclusion

If praise for its subject is usually quite measured, the anthology gives freer rein to scorn for his various opponents. ‘J.C.’ is also an advocacy poem that laments negative treatment by the media

‘On your unsuitability for high office’ recognizes that press attacks begin as soon as they realise / you might succeed in changing/more than the occasional / light bulb.

As for political opponents, there is withering contempt for David Cameron’s cheap point-scoring at PMQ’s about Corbyn’s dress code in ‘Have with you to Savile Row’. Nor do the posturings of other members of the Tory party go un-noticed: ‘Twas Brexit and the slithy Gove / did frottercrutch in dwarfish glee (‘Stabberjocky’); and a characterisation of the current government’s manifesto as

This comes from ‘Tell me lies about the austerity plan’ – which is of course a (well-done) pastiche of Adrian Mitchell’s famous ‘Tell me lies about Vietnam’. It does not limit itself to attacking the Conservatives but – like several other pieces in the anthology – also engages in retrospective criticism of ‘Blairites’ and Tony Blair’s legacy.

Adversaries from Corbyn’s own party are attacked in a more generalised way in ‘The seven ages of a Labour MP’ which run from posing and strutting in the NUS to being sans teeth, sans brain, sans guts, sans principles. ‘Song of the knives-in-the-backbenchers’ (something of a tour de force based on the Bernstein-Sondheim song ‘Gee Officer Krupke’ from West Side Story) has some of Corbyn’s internal opponents protesting

The ‘advice poems’ cover quite a wide range of policy areas. Sympathy for immigrants and the plight of refugees is one of the most common – giving the lie to they come over ‘ere y’know / and get everything via a neat parable on Muntjac deer whose tiny migrant hooves barely dent / the damp ground. ‘Scarlet Macaws’ makes an eloquent plea for diversity, tolerance and freedom from exploitation; while, in contrast, the uncaring pressures of austerity are well captured in ‘Tory Story’:

(This resonates well with the recently released Ken Loach film I, Daniel Blake about the rigidity of the benefit system.)

‘Maiden Speech’ appears to take on the political elite’s blind faith in neo-liberal capitalism; and ‘A Scream in 1890’ reminds us of Victorian factory conditions which current economic theories may be ready to justify all over again. ‘The Anthropocene’ tackles the even grosser blindness to climate change by mocking the feeble refrain how were we to know? Meanwhile ‘The Blame’ skewers a very English problem: Bloody class. The common bloody shame.

These few brief extracts should give an impression that this is a varied and lively selection of poems seeking wholeheartedly to engage with issues that genuinely matter. This is a truthful impression; and yet I could wish the book felt a little less ‘well-behaved’. It is perhaps unfortunate that I recently visited the V & A exhibition You Say You Want a Revolution? and could not help contrasting the extravagant (and, yes, sometimes silly) enthusiasm for change in the 1960s with the more muted and passive responses in the country at large in the face of current causes of discontent. I would have liked to find more pages in this anthology crackling with fire and passion. There are certainly sparks and flashes – not least in the Mitchell and Sondheim pastiche pieces. But these also have an unintended consequence of slightly overshadowing other poems in the book by reminding us what magnificently memorable results can be achieved when fine poets/lyricists turn their imagination and language skills loose on big issues. All that being said, however, this is a book to be welcomed and one to be read and re-read because the poems have a cumulative effect. It should also be seen as a model and an encouragement to other poets and publishers to get some well-crafted rhetoric out into the world of political debate. There have been precious few ‘fine words’ in recent campaigning.

In conclusion, it will perhaps have been noted that I have not mentioned any of the featured poets by name – merely given titles for any quoted poems. An anthology is a cooperative venture and all contributors play some part in the overall impact; hence, as a reviewer, I find I am increasingly reluctant to single out certain authors just because their piece happens to be neatly quotable within my line of critical argument. Such reluctance to name names is oddly intensified in the present special case because I find myself troubled by a cult of personality that seems to have grown up around Jeremy Corbyn himself (and which might be further enhanced by the existence of this collection). In fairness, however, one of the poems in the book (‘Something happened’) does confront this question – and this can have the last word:

They like to pretend it’s all about him but it’s not it’s all about usBy Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, economics, poetry reviews, politics, society, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, economics, poetry, politics, society, Thomas Ovans