Poetry review – VELVEL’S VIOLIN: Wendy Klein reviews a collection by Jacqueline Saphra whose themes have acquired even more depth and significance in light of post-publication events

Velvel’s Violin

Jacqueline Saphra

Nine Arches Press

ISBN: 978-1-913437-74-9

eISBN: 978-1-913437-75-6

£10.99

Velvel’s Violin

Jacqueline Saphra

Nine Arches Press

ISBN: 978-1-913437-74-9

eISBN: 978-1-913437-75-6

£10.99

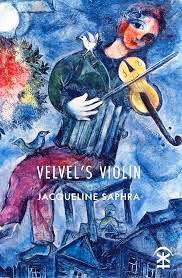

If I was not already a dedicated fan of Jacqueline Saphra’s work, already well-disposed towards her latest publication, I would have been seduced at once by the cover of this collection: ‘The Blue Violinist’, by the well-known Belorussian-born French painter, Marc Chagall. Activist, playwright, and poet, Saphra, like Chagall, brings the political, whimsical, and downright humorous to her work, making the artist’s fiddler the perfect image for this book. Like the precariousness of balancing on a rooftop playing the violin, she manages the balancing act, simultaneously intertwining her own personal history.

In a recent review in Magma 88, Lisa Kelly notes that ‘Saphra is a virtuoso in form’. She goes on to comment that while Velvel’s Violin reaffirms this, the fact that this book explores the poet’s relationship with her Jewish identity and ‘a wider examination of the Jewish diaspora, it ‘refuses to rest easy.’ Indeed, coming out in July 2023, not long before the events of 7 October, it barely had a chance to make its way into the world before the wildly contradictory views about the conflict between Israel and Palestine exploded everywhere. The public view, initially supportive towards Israel has over time been skewed, resulting in a shocking increase in overt anti-Semitism. Saphra’s narrative, which refuses to take sides, speaks to the present moment.

Exquisitely laid out in four sections titled in English, followed by the Hebrew transliteration of each number: Zero, Efes, One, Achat, Two, Shtayeem, Three, Shalosh, Four Arbah, followed by the original letters in Hebrew script, it speaks to the amalgamation of Judaism between cultures. In the first poem “Prologue”, the poet introduces her theme through the figure of Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam in Greek mythology who was endowed with the gift of prophecy but fated never to be believed. In an ingenious way to represent the shifting ground between past and present, to frame her own story, Saphra writes:

History becomes

Cassandra.

Done over

confused

she foretells

the past

and offers it

to the future.

As predicted

the project

is doomed.

The present

believes her

but doesn’t

consider it

news.

Next, in emphatic tercets (“Tomaszów Lubelski”), boosted by their brevity, Saphra lays out the dilemma of telling the story truthfully, knowing it may never really be believed, or even considered very important. Her diaspora continues with travel, presumably to the last known place of a lost family member: ‘…the family house /at least we thought / it was the family house…’ The speaker and companion pause, but decide not to knock and request a tour for fear of being taken as: ‘one of the Jews / of the recurring nightmare / wailing for reparations.’

Painting a stark image of the Jew forced to wander, still looking over his shoulder at ‘home’, she moves on swiftly to England in a poem in which the title asks “Where?” She replies in the first line ‘Not this England’. The reader is not certain whether she is questioning the choice of England as home ‘…edgy, hedged / and fenced; the safety of the tribe’, or whether she is questioning the possibility of home anywhere for the Jew who might not fit anywhere.

Open your mouth and taste the word Jew.

How it lurks uncertain on the tongue.

Now try Belzec, Palestine, Diaspora.

Palestine, of course is where Jews have tried mightily and almost succeeded, in founding a nation free from the threat of moving on again. This theme is carried forward and accentuated in the next piece “Anxious Jewish Poem”, describing an England where ‘Jewish Brits are quiet, mostly hiding / under hats and breathing lightly …’ She goes on to explore the risk of being too visible where ‘…red paint / spits the yids, the yids, Fagins, Shylocks, still / the Jewish money gags…’

That this is a serious book is undeniable, but it is laced with the familiar gallows humour which has been the default note of Jews in peril from Shylock to Portnoy. Someone famous has certainly said that humour is always serious, and the proof is everywhere here. She gives us ‘vintage führer’ in 5 lines:

you can bid

for his face

on ebay

emblazoned

on an ash tray

a piece that only hints at the wit and daring-do of “Going to Bed with Hitler” where the poet riffs for nearly four pages on trying to sleep while reading Hitler: A Biography by Volker Ullrich. She begins with the line ‘Some nights I can’t wait to go to bed / with Hitler’, and goes on to describe how ‘he squats impatient beside the lamp / that burns to illuminate the page.’ She muses on whether going to bed with Hitler could be profitable, finding that she was permanently sleep deprived ‘due to his frequent / and triumphant expostulations. / Blitzkrieg! he yelled at irregular / intervals Blitzkrieg!’ I’m afraid you will have to read the book to find out how the story ends.

There are vivid and poignant poems that comment on visits to places of holocaust history, including “Poland 1985”, ‘and “Bavaria”. In particular there is is a detailed and solemn meditation on Berlin “Remains – Berlin 1945” where the poet asks ‘do you really want to know / the Red Army retrieved /enough teeth / from a crater near the bunker to identify the führer’s bite / upper jaw bridgework.’

Seemingly reluctant to leave the reader with the awfulness, Saphra writes a poem titled, “is the madness caused by the poetry or is the poetry caused by the madness” and concludes the third section (Shalosh) with “The News and the Blackbird” in which she allows herself to move away from, ‘the warring world’ and notice the blackbird who ‘sang suddenly in the key / of joy: Look out! Look up’ and what could she do but obey. This positivity is manifested through relationship, the sense of how home / identity is arrived at through love, through Mazel (luck), and in the poem with that title dedicated to her husband, Robin: ‘chancing in / with your smile on show as I write this poem.’

I began this review feeling unequal to the task. So much is so close to my own history, the Yiddish and Hebrew, the atheism that sits comfortably alongside the observation of holidays, the Judaism of family. Could I be an objective reviewer when Velvel’s violin that no one knew how to play sits alongside my grandfather’s unused tallit (prayer shawl)? I think yes, because this is a book about our common humanity, which, to quote Lisa Kelly coming ‘at time of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, urges love and vigilance in equal measure.’ Everyone on every side of every divide should read it with close attention, relish it and, yes, enjoy it, too.

Apr 4 2024

London Grip Poetry Review – Jacqueline Saphra

Poetry review – VELVEL’S VIOLIN: Wendy Klein reviews a collection by Jacqueline Saphra whose themes have acquired even more depth and significance in light of post-publication events

If I was not already a dedicated fan of Jacqueline Saphra’s work, already well-disposed towards her latest publication, I would have been seduced at once by the cover of this collection: ‘The Blue Violinist’, by the well-known Belorussian-born French painter, Marc Chagall. Activist, playwright, and poet, Saphra, like Chagall, brings the political, whimsical, and downright humorous to her work, making the artist’s fiddler the perfect image for this book. Like the precariousness of balancing on a rooftop playing the violin, she manages the balancing act, simultaneously intertwining her own personal history.

In a recent review in Magma 88, Lisa Kelly notes that ‘Saphra is a virtuoso in form’. She goes on to comment that while Velvel’s Violin reaffirms this, the fact that this book explores the poet’s relationship with her Jewish identity and ‘a wider examination of the Jewish diaspora, it ‘refuses to rest easy.’ Indeed, coming out in July 2023, not long before the events of 7 October, it barely had a chance to make its way into the world before the wildly contradictory views about the conflict between Israel and Palestine exploded everywhere. The public view, initially supportive towards Israel has over time been skewed, resulting in a shocking increase in overt anti-Semitism. Saphra’s narrative, which refuses to take sides, speaks to the present moment.

Exquisitely laid out in four sections titled in English, followed by the Hebrew transliteration of each number: Zero, Efes, One, Achat, Two, Shtayeem, Three, Shalosh, Four Arbah, followed by the original letters in Hebrew script, it speaks to the amalgamation of Judaism between cultures. In the first poem “Prologue”, the poet introduces her theme through the figure of Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam in Greek mythology who was endowed with the gift of prophecy but fated never to be believed. In an ingenious way to represent the shifting ground between past and present, to frame her own story, Saphra writes:

Next, in emphatic tercets (“Tomaszów Lubelski”), boosted by their brevity, Saphra lays out the dilemma of telling the story truthfully, knowing it may never really be believed, or even considered very important. Her diaspora continues with travel, presumably to the last known place of a lost family member: ‘…the family house /at least we thought / it was the family house…’ The speaker and companion pause, but decide not to knock and request a tour for fear of being taken as: ‘one of the Jews / of the recurring nightmare / wailing for reparations.’

Painting a stark image of the Jew forced to wander, still looking over his shoulder at ‘home’, she moves on swiftly to England in a poem in which the title asks “Where?” She replies in the first line ‘Not this England’. The reader is not certain whether she is questioning the choice of England as home ‘…edgy, hedged / and fenced; the safety of the tribe’, or whether she is questioning the possibility of home anywhere for the Jew who might not fit anywhere.

Palestine, of course is where Jews have tried mightily and almost succeeded, in founding a nation free from the threat of moving on again. This theme is carried forward and accentuated in the next piece “Anxious Jewish Poem”, describing an England where ‘Jewish Brits are quiet, mostly hiding / under hats and breathing lightly …’ She goes on to explore the risk of being too visible where ‘…red paint / spits the yids, the yids, Fagins, Shylocks, still / the Jewish money gags…’

That this is a serious book is undeniable, but it is laced with the familiar gallows humour which has been the default note of Jews in peril from Shylock to Portnoy. Someone famous has certainly said that humour is always serious, and the proof is everywhere here. She gives us ‘vintage führer’ in 5 lines:

a piece that only hints at the wit and daring-do of “Going to Bed with Hitler” where the poet riffs for nearly four pages on trying to sleep while reading Hitler: A Biography by Volker Ullrich. She begins with the line ‘Some nights I can’t wait to go to bed / with Hitler’, and goes on to describe how ‘he squats impatient beside the lamp / that burns to illuminate the page.’ She muses on whether going to bed with Hitler could be profitable, finding that she was permanently sleep deprived ‘due to his frequent / and triumphant expostulations. / Blitzkrieg! he yelled at irregular / intervals Blitzkrieg!’ I’m afraid you will have to read the book to find out how the story ends.

There are vivid and poignant poems that comment on visits to places of holocaust history, including “Poland 1985”, ‘and “Bavaria”. In particular there is is a detailed and solemn meditation on Berlin “Remains – Berlin 1945” where the poet asks ‘do you really want to know / the Red Army retrieved /enough teeth / from a crater near the bunker to identify the führer’s bite / upper jaw bridgework.’

Seemingly reluctant to leave the reader with the awfulness, Saphra writes a poem titled, “is the madness caused by the poetry or is the poetry caused by the madness” and concludes the third section (Shalosh) with “The News and the Blackbird” in which she allows herself to move away from, ‘the warring world’ and notice the blackbird who ‘sang suddenly in the key / of joy: Look out! Look up’ and what could she do but obey. This positivity is manifested through relationship, the sense of how home / identity is arrived at through love, through Mazel (luck), and in the poem with that title dedicated to her husband, Robin: ‘chancing in / with your smile on show as I write this poem.’

I began this review feeling unequal to the task. So much is so close to my own history, the Yiddish and Hebrew, the atheism that sits comfortably alongside the observation of holidays, the Judaism of family. Could I be an objective reviewer when Velvel’s violin that no one knew how to play sits alongside my grandfather’s unused tallit (prayer shawl)? I think yes, because this is a book about our common humanity, which, to quote Lisa Kelly coming ‘at time of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, urges love and vigilance in equal measure.’ Everyone on every side of every divide should read it with close attention, relish it and, yes, enjoy it, too.