.

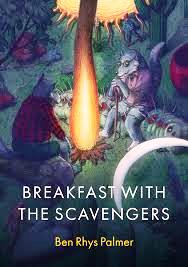

Poetry review – BREAKFAST WITH THE SCAVENGERS: Pat Edwards finds Ben Rhys Palmer’s collection to be a bit of a wake-up call

Breakfast with the Scavengers

Ben Rhys Palmer

Parthian

ISBN 978-1-917140-56-0

£10

Breakfast with the Scavengers

Ben Rhys Palmer

Parthian

ISBN 978-1-917140-56-0

£10

Scavengers – those creatures which make use of the leftovers others discard – are perhaps the original re-cyclers and might deserve to be admired were it not for the negative connotations that often go with the word. The title for this collection actually comes from the second poem, where a hyena and a vulture discuss how much easier it would be “without Old Misery Guts stomping about.” The reader can only assume they are referring to us, that is to mankind, “who persists in peddling his preposterous tales.”

Interestingly, the opening poem is ‘Mi Lucha’, which translates from the Spanish to Mein Kampf or My Struggle, Hitler’s infamous political manifesto. Written in ten two-line stanzas, five of which start with ‘I’, the poem immediately places us in Mexico, the country where Palmer now resides. References include El Santo, the famous masked Mexican wrestler, and peyote, a psychoactive fruit. I only know these things because I looked them up; I’m no expert in all things Mexican. The images in the poem are pretty brutal – coyotes, a priestess with a penchant for mathematical torture, “tyrants, demons, fiends”, until the ‘I’ of the poem delivers their “body to the care of the deep.” So, I guess that we, the readers, are in for one helluva ride, and this is just part one.

We encounter ‘Eden the Robot Gardener’ who finds Adam and Eve “cold and stiff in their kitchen one morning”, and we are taken on a reimagined version of our evolution from fish. We get references to the iconic Welsh wrestler, Adrian Street, and experience a world of ostrich-racing that takes a dramatic turn, saved by a spot of knitting. It’s perhaps at this point the reader starts reeling and asks just what am I reading? But that’s a good thing – who wants same old, same old? And the poet’s advice? – “to be brave.”

Seriously though, Palmer challenges us to think about contemporary life with its “too much espresso and social media”; and he does so by introducing characters such as Puck and a fancy dress tiger, and by recommending a good night of dancing “so hard the stylus skips in every song.” The poet uses a sonnet to sing the praises of famous restauranteur Jay Fai, and elsewhere he dreams of having a crack at taming Cleopatra via “kick-boxing, or chess – to satisfy her taste for strategy.” Readers may go along with the endless strangeness, the absurdity, or find it tiresome – there’s no doubt you will have either have embraced it or be still struggling by the time you’ve reached the end of part one.

Part two opens with the most bold ‘First Date’ where one partner notices “we’re bleeding”, only for the other to reply “I know.” The intensity is evident. This whole section examines the characteristics of love: at times it is “a lion leaping through flaming hoops” while at others it is “the fart that skips/from your horse’s arse as it picks up pace.” Love is difficult so it’s best to “keep/a homemade phaser gun/set to stun – should things get/out of hand.” Love can even come to ‘Bellyache Jake’ who we find “strolling hand-in-hand/with an orangutang in a floral dress.”

Palmer does sonnets well. After all, they can be the language of love, so why not write one about that Welsh wrestler mentioned earlier – “the heart-throb heel, the Sadist in sequins”? There’s a poem too about how they do wrestling in Mexico, ‘Lucha Libre’ style, looking “like kinky superheroes or glammed-up gimps.” The poet has an original way of mixing imagery from his growing-up in Wales with scenes from his adopted Mexico. This makes for a special freshness.

The clown references in a couple of poems keep up a sense of menace, as do birthday balloons, until we arrive at ‘The Funeral’ where “they served bottle after bottle of a shoddy red” and the poet becomes devilish, acquiring horns “as if they’d been growing my whole life.” And if this jeopardy wasn’t bad enough, we are shown children playing with Japanese ‘Sashimi’ knives used for thinly slicing raw meat and fish. Ah yes, this is the poet’s way of reminding us that love sometimes doesn’t last,

Then I remembered: my wife walked out

days ago. We have no kids.

Part three is where some of the reality kicks in and “regret clogs the plug hole”. I enjoyed the little Welsh reference as the poet sets out “sodden and shivering, in a coracle made of empty shampoo bottles.” There’s a sense of doom with “the shadow of a buzzard” and there are games, disappointments, plus an adventurous Minotaur, part man, part bull, who forgets the rice cakes ordered by his wife. The wrestler makes a sad reappearance in another sonnet, flaunting his unexpected success “back in Blaina, at the wretched old pit.” ‘Sabanas Blancas’ evokes the nostalgia of a once lived-in house and we hear the tale of ‘Pfeilstorch’ reminding us that even epic endurance can end in the indignity of “a bullet to the lung” and “stuffing”.

We are clearly in a “demented world” (‘Seasick’) and desperation is setting in

Scientists study

you for the key to reversing ageing

curing cancer, dethroning death

(‘Axolotl’)

In ‘Beached’ we toast “the end of the world”. But then in the poems ‘Visitors’ and ‘Eulogy’ Palmer at last drops the absurdity because these are poems about the harsh reality of a death in the family. There’s no room here for going into deeply imaginative game-playing – this is the stuff of loss, and only straight-talking will do. Now the reader gets that and relates to it.

Part four of this collection has a gentler feel, as if the poet has been changed by his experiences. He displays an interest in nature, in simplicity. Of course, there’s another sonnet about our wrestler – Palmer seemingly can’t help himself – and there’s a poem about remembering Lorca’s elegy for a dead child. But even this feels like the road to recovery. Perhaps some proof comes in the poem about Leonora Carrington’s painting which speaks of a “feathered creature [that] will gobble up all our sorrows.” Palmer proudly celebrates his relative, Rebecca Williams, who emigrated from Wales to Patagonia, but also emphasises his own love of Mexico.

Palmer chooses to close the collection with a poem about the transgender performer La Dany. This marks a blatant and provocative return to the outrageous and absurd, but we forgive him because that’s part of his life now in this colourful neck of the woods and we’re glad of having been taken on the excursion.

This collection won’t be for everyone – it’s edgy, sometimes like fingernails scratching down an old-school blackboard – but you can’t ignore it because it makes you read it. I’m pleased I did. Indeed it woke me from a bit of a poetry coma and no one wants to be in one of those! If your poetry world is feeling a bit stale, this is definitely for you. Enjoy your breakfast…

Nov 19 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Ben Rhys Palmer

.

Poetry review – BREAKFAST WITH THE SCAVENGERS: Pat Edwards finds Ben Rhys Palmer’s collection to be a bit of a wake-up call

Scavengers – those creatures which make use of the leftovers others discard – are perhaps the original re-cyclers and might deserve to be admired were it not for the negative connotations that often go with the word. The title for this collection actually comes from the second poem, where a hyena and a vulture discuss how much easier it would be “without Old Misery Guts stomping about.” The reader can only assume they are referring to us, that is to mankind, “who persists in peddling his preposterous tales.”

Interestingly, the opening poem is ‘Mi Lucha’, which translates from the Spanish to Mein Kampf or My Struggle, Hitler’s infamous political manifesto. Written in ten two-line stanzas, five of which start with ‘I’, the poem immediately places us in Mexico, the country where Palmer now resides. References include El Santo, the famous masked Mexican wrestler, and peyote, a psychoactive fruit. I only know these things because I looked them up; I’m no expert in all things Mexican. The images in the poem are pretty brutal – coyotes, a priestess with a penchant for mathematical torture, “tyrants, demons, fiends”, until the ‘I’ of the poem delivers their “body to the care of the deep.” So, I guess that we, the readers, are in for one helluva ride, and this is just part one.

We encounter ‘Eden the Robot Gardener’ who finds Adam and Eve “cold and stiff in their kitchen one morning”, and we are taken on a reimagined version of our evolution from fish. We get references to the iconic Welsh wrestler, Adrian Street, and experience a world of ostrich-racing that takes a dramatic turn, saved by a spot of knitting. It’s perhaps at this point the reader starts reeling and asks just what am I reading? But that’s a good thing – who wants same old, same old? And the poet’s advice? – “to be brave.”

Seriously though, Palmer challenges us to think about contemporary life with its “too much espresso and social media”; and he does so by introducing characters such as Puck and a fancy dress tiger, and by recommending a good night of dancing “so hard the stylus skips in every song.” The poet uses a sonnet to sing the praises of famous restauranteur Jay Fai, and elsewhere he dreams of having a crack at taming Cleopatra via “kick-boxing, or chess – to satisfy her taste for strategy.” Readers may go along with the endless strangeness, the absurdity, or find it tiresome – there’s no doubt you will have either have embraced it or be still struggling by the time you’ve reached the end of part one.

Part two opens with the most bold ‘First Date’ where one partner notices “we’re bleeding”, only for the other to reply “I know.” The intensity is evident. This whole section examines the characteristics of love: at times it is “a lion leaping through flaming hoops” while at others it is “the fart that skips/from your horse’s arse as it picks up pace.” Love is difficult so it’s best to “keep/a homemade phaser gun/set to stun – should things get/out of hand.” Love can even come to ‘Bellyache Jake’ who we find “strolling hand-in-hand/with an orangutang in a floral dress.”

Palmer does sonnets well. After all, they can be the language of love, so why not write one about that Welsh wrestler mentioned earlier – “the heart-throb heel, the Sadist in sequins”? There’s a poem too about how they do wrestling in Mexico, ‘Lucha Libre’ style, looking “like kinky superheroes or glammed-up gimps.” The poet has an original way of mixing imagery from his growing-up in Wales with scenes from his adopted Mexico. This makes for a special freshness.

The clown references in a couple of poems keep up a sense of menace, as do birthday balloons, until we arrive at ‘The Funeral’ where “they served bottle after bottle of a shoddy red” and the poet becomes devilish, acquiring horns “as if they’d been growing my whole life.” And if this jeopardy wasn’t bad enough, we are shown children playing with Japanese ‘Sashimi’ knives used for thinly slicing raw meat and fish. Ah yes, this is the poet’s way of reminding us that love sometimes doesn’t last,

Part three is where some of the reality kicks in and “regret clogs the plug hole”. I enjoyed the little Welsh reference as the poet sets out “sodden and shivering, in a coracle made of empty shampoo bottles.” There’s a sense of doom with “the shadow of a buzzard” and there are games, disappointments, plus an adventurous Minotaur, part man, part bull, who forgets the rice cakes ordered by his wife. The wrestler makes a sad reappearance in another sonnet, flaunting his unexpected success “back in Blaina, at the wretched old pit.” ‘Sabanas Blancas’ evokes the nostalgia of a once lived-in house and we hear the tale of ‘Pfeilstorch’ reminding us that even epic endurance can end in the indignity of “a bullet to the lung” and “stuffing”.

We are clearly in a “demented world” (‘Seasick’) and desperation is setting in

Scientists study you for the key to reversing ageing curing cancer, dethroning death (‘Axolotl’)In ‘Beached’ we toast “the end of the world”. But then in the poems ‘Visitors’ and ‘Eulogy’ Palmer at last drops the absurdity because these are poems about the harsh reality of a death in the family. There’s no room here for going into deeply imaginative game-playing – this is the stuff of loss, and only straight-talking will do. Now the reader gets that and relates to it.

Part four of this collection has a gentler feel, as if the poet has been changed by his experiences. He displays an interest in nature, in simplicity. Of course, there’s another sonnet about our wrestler – Palmer seemingly can’t help himself – and there’s a poem about remembering Lorca’s elegy for a dead child. But even this feels like the road to recovery. Perhaps some proof comes in the poem about Leonora Carrington’s painting which speaks of a “feathered creature [that] will gobble up all our sorrows.” Palmer proudly celebrates his relative, Rebecca Williams, who emigrated from Wales to Patagonia, but also emphasises his own love of Mexico.

Palmer chooses to close the collection with a poem about the transgender performer La Dany. This marks a blatant and provocative return to the outrageous and absurd, but we forgive him because that’s part of his life now in this colourful neck of the woods and we’re glad of having been taken on the excursion.

This collection won’t be for everyone – it’s edgy, sometimes like fingernails scratching down an old-school blackboard – but you can’t ignore it because it makes you read it. I’m pleased I did. Indeed it woke me from a bit of a poetry coma and no one wants to be in one of those! If your poetry world is feeling a bit stale, this is definitely for you. Enjoy your breakfast…