Poetry review – LEGWORK: Nick Cooke finds much that is rewarding and moving within the dense language of Michael Vince’s poems

Legwork

Michael Vince

Mica Press

ISBN 978-1-869848-38-5

pp 66 £10.00

Legwork

Michael Vince

Mica Press

ISBN 978-1-869848-38-5

pp 66 £10.00

Perhaps better known to English language teachers as the author of successful grammar practice books, Michael Vince has a distinguished record as a poet, with nine previous collections, including two published by Carcanet. Reviewing a previous Mica book, Plain Text (2015), for London Grip, I recommended that the poet ‘pursue the less prolix path alongside what seems his “default” expository style, even more than he has done in this thought-provoking and moving collection.’ Of course there was no reason the poet should have heeded my advice, but for what it’s worth I found myself echoing the same reservations while reading Legwork, even as I also felt this latest work to be, again, both thought-provoking and moving, particularly in its second half.

This book is divided into four sections, of which the first is set during a trip/holiday in Greece, featuring a combination of detailed observations and empathetic responses to the local people Vince encounters. The opening poem, “Generosity”, embraces both the thrill of risk and the warmth of human proximity, as a carefree Greek bus driver endangers the lives of his passengers by driving with one arm around his girlfriend. The girlfriend breaks off from the canoodling long enough to pluck some figs from a nearby tree and pass them round to the passengers, who ‘eat [them] with syrupy hands and chins’ and become ‘an unexpected community’, so the warmth wins out, though the risk is not fully excised:

… the bus starts up again

and lurches its way down as some

applause breaks out at the back

while the driver and his girl wave

and exchange sweet generous kisses.

.

A comparable combination of humanity and jeopardy marks the excellent “Bin”, where a supposedly ordinary rubbish bin, initially used as a metaphor for some remarks on the ultimate disposability of life, suddenly encompasses very literal horror, as a whimper from within reveals that it contains ‘three thirsty / and hungry pups, left to die’. The speaker performs his humane duty, carrying them to a nearby filling station, where he spots a man he’s sure is the culprit, ‘lurking’. Wisely, Vince confines any judgment on the person’s conduct to that single word, and the poem’s all the better for it.

“Lost for Words” begins with ‘a sea of words, meanings darkening / and closing in, ambiguity freshening, / and the voyage onward doubtful.’ Our own journey through the rest of the book is certainly shot through with uncertainty. In “Misty Morning” there’s more than a faint echo of Four Quartets in the phrasing of Vince’s conclusion:

and we ask ourselves whether

we had really seen those things

properly before, and also whether

we would ever see them again,

the same uncovering, another trip

back to the cave just down the road.

.

And T.S. Eliot’s frustration with language that ‘will not stay still’ seems pertinent to the ending of “Fish”, the title poem of the second section, where ‘ideas swim about / in the glass-walled Aquarium’. Like the fish themselves, thoughts can only be artificially constrained, yet are ultimately ephemeral, as they ‘seek for an answer, then vanish / into their dim yet shiny world, / but re-appear over and over / unwilling to stay still’.

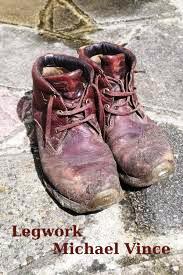

Next in the sequence is the title poem, which establishes walking – increasingly a key theme, with the book’s cover showing a pair of well-worn hiking boots – as an arguably somewhat laboured metaphor for intellectual endeavour, and the quest for philosophical solutions. Initially, in fact, it’s presented as what in my Latin-studying days I’d have called a Virgilian simile:

Going over the same rough ground

seeking an answer, it’s a matter

of setting things out, finding the route,

as a distance walker first lays out

maps…

.

The ending evokes the pleasure derived from the effort invested, as much as the knowledge gained, though in what proves quite a typical use of qualifiers, Vince notes ‘it’s almost a joy’ to descend from the mountain, ‘now that an ache in calf and thigh / embodies the process of legwork.’

Sometimes – to return to my earlier-stated caveat – Vince’s recurring tendency to use very long, verbose sentences doesn’t quite justify Edmund Prestwich’s reference (in a review of an earlier book, quoted on the back cover) to his ‘syntactical mastery’, because often the syntax either goes slightly awry or it does little to enhance the effect of the poetry, making some passages seem little more than prose chopped up into lines of roughly equal length. Space limitations mean I’ll quote just one, of several instances:

The guesses drew us together along

the soft rutted path; at a distance

sunlight made the ruin of a small

temple, which would have been

better in a dry spot on the skyline

but neglected above had slipped

down the slope, colonies of brambles

replacing the incised sculptural

panels depicting a procession

of the gods, old tin cans, plastic

chairs, odd parts of abandoned cars

added as rubbish to the pile,

rather than gifts and prayers

aimed at an equally unlooked-for

acceptance, a rising mist of the known

from the unknown sliding at our feet.

(“Appearance”)

.

A full stop after ‘gods’, at the very least, would surely not have been amiss. Far more effective are poems in which less serpentine syntax makes for a punchier, more engaging style. I also felt Vince would do well to consider using rhyme more frequently, as it seems to impose a beneficial discipline. Witness “Diggin”’, from the third section, ‘Visiting Relatives Can be Difficult.’ Addressed to the poet’s father, this has obvious Heaney allusions but is a fine poem in its own right, compressing autobiographical detail into finely-wrought vignettes, with the rhymes providing a suitably memorial-style frame for the tone of elegiac nostalgia:

When your rhythmic hoe and spade

passed on to me down a line of field-labourers,

I was the careless one who dropped our ancestors,

While you lived in the word that held the shapes they made

in strips of field, where neighbours rose at four

to tend their plots before their working day.

.

Where the collection really scores highly is its very accomplished final section, entitled ‘Final Shore’, in which myth creeps up on reality’s shoulder, so to speak, through a complex but well-controlled culmination. “John “Walking” Stewart 1474-1822” celebrates the life of a walking guru, said to have influenced Wordsworth, whose contribution to society is both mocked and revered:

Some passers-by jeer at him,

others ask his blessing, this restless philosopher,

busying on his way, intending as he goes

pace by pace towards the mind’s resting-place.

.

Good luck with that, the reader might reasonably remark, on the chances of the mind (at least one like Vince’s) ever finding rest. And that idea is central to the closing poem, “Mythical Voyage”, where Vince’s considerable skill is particularly brought to bear, in imagining a shipwrecked crew spending their time discussing matters of philosophical import. The final lines actually show the poet’s syntactical complexity in a much better light than earlier, as the halting advances of each phrase mimic the steady progress towards understanding – once again echoing Eliot, and picking up the key theme of this book’s title poem – that he has been seeking throughout the book, and presumably his career:

At night, round the fire, they would talk it over,

weigh up the chances, share a hidden bottle,

and agree not to mention, or at least not for now,

that they hadn’t come far, just a few hours’ talk,

from the singing priests, and the sacrifices

and the palace and the fortress they’d started from.

Nov 4 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Michael Vince

Poetry review – LEGWORK: Nick Cooke finds much that is rewarding and moving within the dense language of Michael Vince’s poems

Perhaps better known to English language teachers as the author of successful grammar practice books, Michael Vince has a distinguished record as a poet, with nine previous collections, including two published by Carcanet. Reviewing a previous Mica book, Plain Text (2015), for London Grip, I recommended that the poet ‘pursue the less prolix path alongside what seems his “default” expository style, even more than he has done in this thought-provoking and moving collection.’ Of course there was no reason the poet should have heeded my advice, but for what it’s worth I found myself echoing the same reservations while reading Legwork, even as I also felt this latest work to be, again, both thought-provoking and moving, particularly in its second half.

This book is divided into four sections, of which the first is set during a trip/holiday in Greece, featuring a combination of detailed observations and empathetic responses to the local people Vince encounters. The opening poem, “Generosity”, embraces both the thrill of risk and the warmth of human proximity, as a carefree Greek bus driver endangers the lives of his passengers by driving with one arm around his girlfriend. The girlfriend breaks off from the canoodling long enough to pluck some figs from a nearby tree and pass them round to the passengers, who ‘eat [them] with syrupy hands and chins’ and become ‘an unexpected community’, so the warmth wins out, though the risk is not fully excised:

… the bus starts up again and lurches its way down as some applause breaks out at the back while the driver and his girl wave and exchange sweet generous kisses. .A comparable combination of humanity and jeopardy marks the excellent “Bin”, where a supposedly ordinary rubbish bin, initially used as a metaphor for some remarks on the ultimate disposability of life, suddenly encompasses very literal horror, as a whimper from within reveals that it contains ‘three thirsty / and hungry pups, left to die’. The speaker performs his humane duty, carrying them to a nearby filling station, where he spots a man he’s sure is the culprit, ‘lurking’. Wisely, Vince confines any judgment on the person’s conduct to that single word, and the poem’s all the better for it.

“Lost for Words” begins with ‘a sea of words, meanings darkening / and closing in, ambiguity freshening, / and the voyage onward doubtful.’ Our own journey through the rest of the book is certainly shot through with uncertainty. In “Misty Morning” there’s more than a faint echo of Four Quartets in the phrasing of Vince’s conclusion:

and we ask ourselves whether we had really seen those things properly before, and also whether we would ever see them again, the same uncovering, another trip back to the cave just down the road. .And T.S. Eliot’s frustration with language that ‘will not stay still’ seems pertinent to the ending of “Fish”, the title poem of the second section, where ‘ideas swim about / in the glass-walled Aquarium’. Like the fish themselves, thoughts can only be artificially constrained, yet are ultimately ephemeral, as they ‘seek for an answer, then vanish / into their dim yet shiny world, / but re-appear over and over / unwilling to stay still’.

Next in the sequence is the title poem, which establishes walking – increasingly a key theme, with the book’s cover showing a pair of well-worn hiking boots – as an arguably somewhat laboured metaphor for intellectual endeavour, and the quest for philosophical solutions. Initially, in fact, it’s presented as what in my Latin-studying days I’d have called a Virgilian simile:

Going over the same rough ground seeking an answer, it’s a matter of setting things out, finding the route, as a distance walker first lays out maps… .The ending evokes the pleasure derived from the effort invested, as much as the knowledge gained, though in what proves quite a typical use of qualifiers, Vince notes ‘it’s almost a joy’ to descend from the mountain, ‘now that an ache in calf and thigh / embodies the process of legwork.’

Sometimes – to return to my earlier-stated caveat – Vince’s recurring tendency to use very long, verbose sentences doesn’t quite justify Edmund Prestwich’s reference (in a review of an earlier book, quoted on the back cover) to his ‘syntactical mastery’, because often the syntax either goes slightly awry or it does little to enhance the effect of the poetry, making some passages seem little more than prose chopped up into lines of roughly equal length. Space limitations mean I’ll quote just one, of several instances:

The guesses drew us together along the soft rutted path; at a distance sunlight made the ruin of a small temple, which would have been better in a dry spot on the skyline but neglected above had slipped down the slope, colonies of brambles replacing the incised sculptural panels depicting a procession of the gods, old tin cans, plastic chairs, odd parts of abandoned cars added as rubbish to the pile, rather than gifts and prayers aimed at an equally unlooked-for acceptance, a rising mist of the known from the unknown sliding at our feet. (“Appearance”) .A full stop after ‘gods’, at the very least, would surely not have been amiss. Far more effective are poems in which less serpentine syntax makes for a punchier, more engaging style. I also felt Vince would do well to consider using rhyme more frequently, as it seems to impose a beneficial discipline. Witness “Diggin”’, from the third section, ‘Visiting Relatives Can be Difficult.’ Addressed to the poet’s father, this has obvious Heaney allusions but is a fine poem in its own right, compressing autobiographical detail into finely-wrought vignettes, with the rhymes providing a suitably memorial-style frame for the tone of elegiac nostalgia:

When your rhythmic hoe and spade passed on to me down a line of field-labourers, I was the careless one who dropped our ancestors, While you lived in the word that held the shapes they made in strips of field, where neighbours rose at four to tend their plots before their working day. .Where the collection really scores highly is its very accomplished final section, entitled ‘Final Shore’, in which myth creeps up on reality’s shoulder, so to speak, through a complex but well-controlled culmination. “John “Walking” Stewart 1474-1822” celebrates the life of a walking guru, said to have influenced Wordsworth, whose contribution to society is both mocked and revered:

Some passers-by jeer at him, others ask his blessing, this restless philosopher, busying on his way, intending as he goes pace by pace towards the mind’s resting-place. .Good luck with that, the reader might reasonably remark, on the chances of the mind (at least one like Vince’s) ever finding rest. And that idea is central to the closing poem, “Mythical Voyage”, where Vince’s considerable skill is particularly brought to bear, in imagining a shipwrecked crew spending their time discussing matters of philosophical import. The final lines actually show the poet’s syntactical complexity in a much better light than earlier, as the halting advances of each phrase mimic the steady progress towards understanding – once again echoing Eliot, and picking up the key theme of this book’s title poem – that he has been seeking throughout the book, and presumably his career: