Poetry review – FOR THE DURATION: Jim Greenhalf finds much to admire in a new collection by Nicholas Bielby

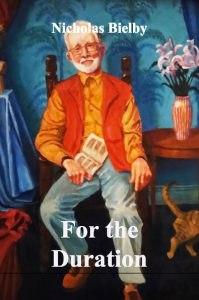

For The Duration

Nicholas Bielby,

Graft Poetry

ISBN 9781068602917,

pp. 92 £10.00 + P&P £2.00

For The Duration

Nicholas Bielby,

Graft Poetry

ISBN 9781068602917,

pp. 92 £10.00 + P&P £2.00

Well, here I am at eighty-five

at my desk and still alive!

The opening lines of Nicholas Bielby’s “Ode to Himself” suggests that this is going to be yet another paean of anxiety from an old codger. But anyone reasonably familiar with Bielby’s published volumes of poetry should know that like the Southern brew, Old Grandad, the best of his poems packs more of a punch than that. And “Ode to Himself” is one of the best.

But the poem, like the rest of the book, is not just about himself. Referencing poet and playwright Big Ben Jonson, who refers to his own as ‘a dainty age’, Bielby holds up a mirror to our own times:

Ours also is a dainty age:

self-righteous snowflakes hold the stage.

Their vicious passions, masquerading as

compassion, rule the public consciousness.

Their wokery has spawned that fascist vulture,

our current cancel culture.

These virtue-signallers, with blood-soaked flags,

tear community to rags.

Being a good poet in this age is not easy because the times demand compromises in some way, either with the truth or the attitudes that others expect a poet to have, saying all the right things about gender, class, history and writing. In spite of the numerous shibboleths rising up like the monstrosities in and around Canary Wharf, Bielby, a seemingly amiable ex-vicar type, goes on cultivating a beguiling tenacity in his well-crafted structures, challenging the tendentious assumptions of our ‘dainty’ age.

Among the fifty-six pieces in this volume are poems about trans-gender, the Qur’an, the scientific quest for the Theory of Everything – flawed from the start because of the flaws in mathematics – as well as reflections on the poet’s own career as a lecturer in India and Bradford, his sixty-year marriage to Sheila, painting and excellent interpretive translations of poems by Rilke and by Goethe on the subjects of ageing and mortality:

You can’t fuck anymore – not without a pill.

The pretty girls see you as safely geriatric.

It’s all a bit sad really. You don’t get to feel joy any more,

or, at least, not very often and not as you once did.

But, don’t go away, this version of Goethe’s “On Old Age” concludes on a note of sensual triumph as the elderly poet happily finds consolation:

… in the immortal words of ‘Old Bill’ Bairnsfather,

“If yer knows of a better ‘ole, go to it!”

And I knows of a better ‘ole for my comfort

and consolation. Yes, skin-to-skin is still win-win!

That’s a lesson for us all.

The voice, Al Alvarez says, is more important than style. Style is what a poet tries for; if he is any good, a voice uniquely his own is what he ends up with. I have come to realise that I trust old Nick’s voice as it ranges across the whole gamut of his experiences as a lusting intellectual, a loving husband, a painter, a poet, a teacher, traveller, gardener, friend and questing intelligence.

His voice can always be trusted especially when the style doesn’t quite live up to his intentions as in win-win after skin-to-skin at the end of the Goethe poem. Nothing more needed to be added after skin-to-skin, but he couldn’t resist rubbing in the joke, the euphony of the rhyme. Not a sin, merely a small stylistic lapse.

The same excellence as in the Goethe poem can be found in other poems such as “The Journey to Egypt”, “Not Like India”, and “A Door Closes” – this last a memoir from childhood when he and two friends, playing spacemen, suddenly become self-conscious about their play and walk away – ;our shame something we couldn’t speak about.’

All this is very well; but what about the two big pieces I referred to earlier: the poems about the Qur’an and the Theory of Everything? I read them both with pretty good concentration one afternoon and was glad I did so. In my judgement both pieces are on the periphery of Bielby’s VIPs: Very Interesting Poems rather than Very Important Poems. Interesting because they communicate his intense willingness to involve himself in the mental mechanics of religious belief and the nature of the universe.

It was the subject matter in part; it was also his thinking-aloud voice wending its way through the nine modulated sections of the Qur’an poem. His tongue-in-cheek “Waiting for Gödel” poem’s Theory of Paradox finale had me reaching for pen and paper with a feeling of pleasurable anticipation. The dubious notion of coming up with a theory about everything in a timeless universe reminds me of Mr Casaubon’s fruitless search in Middlemarch for a symbolic key to explain all ancient religious myths. The paradox, as Bielby says, ‘has to make you laugh.’

There is a poem about Bradford’s architecture and current culture that strikes me as incomplete. It would be better as part of a suite of which “In Bradford Royal Infirmary” could also be a part. This poem begins

I do not belong in this ward of old men

with their scrotal necks, mouths gaping, breath

gargling in dark tunnels, who doze towards death.

Yet here I am, just such a specimen.

This was an experience I had myself last year. The poem concludes with a sentiment which the late television critic AA Gill would have endorsed. When he was in the last throes of a terminal illness in a state hospital he wrote in his last column: ‘It is impossible to be a racist in an NHS hospital,’ or words to that effect. Bielby concludes

Yet it is like the Kingdom of Heaven, here

among us – multi-ethnic, multi-faith

(as it must be): Philippino with

Chinese; black with white; Muslim, Hindu – where

care is compassionate and technical;

where love is totally professional.

I’d have encouraged the search for a better word than totally to describe the professional love of the nursing staff. Vocational, a bit duller perhaps, but I’ve got this thing about how careerism is destroying vocationalism in teaching and nursing. My belief is you cannot teach or communicate anything unless you love it. I like to believe that teachers, nurses and doctors used to feel that way too, until it was drummed out of them by the politics of pay.

“Writing as Serendipity” and “For the Duration”, the title poem, are the two best poems about writing and reading poetry. In the former, he says

I like to work in form and rhyme which then

constrain expression with their discipline

and push forward to conclusion – although

what (or if) that might be, you don’t know.

In the latter, he suggests that, like a photograph, a poem

stops the world for your consideration,

for your attention and evaluation –

evaluation of the work, of life

and re-evaluation of yourself.

There are others, “The Right Words”, for example, which I thought slightly too long marked by too much mental-processing. Bielby is prone to musing publicly about his mental processes.

I very much liked the last verse of “A Wedding Present for Sepp and Monika” with the lines

As you together build the living house

of your uncommon love and common life…

Those phrases, ‘living house’, ‘uncommon love’, ‘common life’ make a happy combination of proper sentiments, utterly different to the kind of slop that usually accompanies the subject of love and marriage. They are typical of the insightful generosity of Bielby’s willingness to celebrate the good in nature, art and ordinary life without being the least sentimental or drippy.

Anne Stevenson’s comparative summary on the back cover is a fair assessment of Bielby’s capabilities: ‘… many of Nicholas Bielby’s poems are among the finest being written today…’ His old man’s “Ode” is worthy of a prize. Of course it won’t get one.

Oct 4 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Nicholas Bielby

Poetry review – FOR THE DURATION: Jim Greenhalf finds much to admire in a new collection by Nicholas Bielby

Well, here I am at eighty-five at my desk and still alive!The opening lines of Nicholas Bielby’s “Ode to Himself” suggests that this is going to be yet another paean of anxiety from an old codger. But anyone reasonably familiar with Bielby’s published volumes of poetry should know that like the Southern brew, Old Grandad, the best of his poems packs more of a punch than that. And “Ode to Himself” is one of the best.

But the poem, like the rest of the book, is not just about himself. Referencing poet and playwright Big Ben Jonson, who refers to his own as ‘a dainty age’, Bielby holds up a mirror to our own times:

Ours also is a dainty age: self-righteous snowflakes hold the stage. Their vicious passions, masquerading as compassion, rule the public consciousness. Their wokery has spawned that fascist vulture, our current cancel culture. These virtue-signallers, with blood-soaked flags, tear community to rags.Being a good poet in this age is not easy because the times demand compromises in some way, either with the truth or the attitudes that others expect a poet to have, saying all the right things about gender, class, history and writing. In spite of the numerous shibboleths rising up like the monstrosities in and around Canary Wharf, Bielby, a seemingly amiable ex-vicar type, goes on cultivating a beguiling tenacity in his well-crafted structures, challenging the tendentious assumptions of our ‘dainty’ age.

Among the fifty-six pieces in this volume are poems about trans-gender, the Qur’an, the scientific quest for the Theory of Everything – flawed from the start because of the flaws in mathematics – as well as reflections on the poet’s own career as a lecturer in India and Bradford, his sixty-year marriage to Sheila, painting and excellent interpretive translations of poems by Rilke and by Goethe on the subjects of ageing and mortality:

You can’t fuck anymore – not without a pill. The pretty girls see you as safely geriatric. It’s all a bit sad really. You don’t get to feel joy any more, or, at least, not very often and not as you once did.But, don’t go away, this version of Goethe’s “On Old Age” concludes on a note of sensual triumph as the elderly poet happily finds consolation:

… in the immortal words of ‘Old Bill’ Bairnsfather, “If yer knows of a better ‘ole, go to it!” And I knows of a better ‘ole for my comfort and consolation. Yes, skin-to-skin is still win-win!That’s a lesson for us all.

The voice, Al Alvarez says, is more important than style. Style is what a poet tries for; if he is any good, a voice uniquely his own is what he ends up with. I have come to realise that I trust old Nick’s voice as it ranges across the whole gamut of his experiences as a lusting intellectual, a loving husband, a painter, a poet, a teacher, traveller, gardener, friend and questing intelligence.

His voice can always be trusted especially when the style doesn’t quite live up to his intentions as in win-win after skin-to-skin at the end of the Goethe poem. Nothing more needed to be added after skin-to-skin, but he couldn’t resist rubbing in the joke, the euphony of the rhyme. Not a sin, merely a small stylistic lapse.

The same excellence as in the Goethe poem can be found in other poems such as “The Journey to Egypt”, “Not Like India”, and “A Door Closes” – this last a memoir from childhood when he and two friends, playing spacemen, suddenly become self-conscious about their play and walk away – ;our shame something we couldn’t speak about.’

All this is very well; but what about the two big pieces I referred to earlier: the poems about the Qur’an and the Theory of Everything? I read them both with pretty good concentration one afternoon and was glad I did so. In my judgement both pieces are on the periphery of Bielby’s VIPs: Very Interesting Poems rather than Very Important Poems. Interesting because they communicate his intense willingness to involve himself in the mental mechanics of religious belief and the nature of the universe.

It was the subject matter in part; it was also his thinking-aloud voice wending its way through the nine modulated sections of the Qur’an poem. His tongue-in-cheek “Waiting for Gödel” poem’s Theory of Paradox finale had me reaching for pen and paper with a feeling of pleasurable anticipation. The dubious notion of coming up with a theory about everything in a timeless universe reminds me of Mr Casaubon’s fruitless search in Middlemarch for a symbolic key to explain all ancient religious myths. The paradox, as Bielby says, ‘has to make you laugh.’

There is a poem about Bradford’s architecture and current culture that strikes me as incomplete. It would be better as part of a suite of which “In Bradford Royal Infirmary” could also be a part. This poem begins

This was an experience I had myself last year. The poem concludes with a sentiment which the late television critic AA Gill would have endorsed. When he was in the last throes of a terminal illness in a state hospital he wrote in his last column: ‘It is impossible to be a racist in an NHS hospital,’ or words to that effect. Bielby concludes

I’d have encouraged the search for a better word than totally to describe the professional love of the nursing staff. Vocational, a bit duller perhaps, but I’ve got this thing about how careerism is destroying vocationalism in teaching and nursing. My belief is you cannot teach or communicate anything unless you love it. I like to believe that teachers, nurses and doctors used to feel that way too, until it was drummed out of them by the politics of pay.

“Writing as Serendipity” and “For the Duration”, the title poem, are the two best poems about writing and reading poetry. In the former, he says

In the latter, he suggests that, like a photograph, a poem

There are others, “The Right Words”, for example, which I thought slightly too long marked by too much mental-processing. Bielby is prone to musing publicly about his mental processes.

I very much liked the last verse of “A Wedding Present for Sepp and Monika” with the lines

Those phrases, ‘living house’, ‘uncommon love’, ‘common life’ make a happy combination of proper sentiments, utterly different to the kind of slop that usually accompanies the subject of love and marriage. They are typical of the insightful generosity of Bielby’s willingness to celebrate the good in nature, art and ordinary life without being the least sentimental or drippy.

Anne Stevenson’s comparative summary on the back cover is a fair assessment of Bielby’s capabilities: ‘… many of Nicholas Bielby’s poems are among the finest being written today…’ His old man’s “Ode” is worthy of a prize. Of course it won’t get one.