Poetry review – UNSUNG: Pat Edwards admires Emma Purshouse’s skill in making poems from the stuff of everyday life

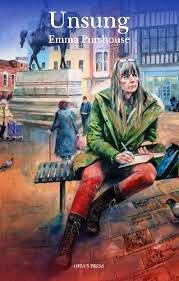

Unsung

Emma Purshouse

Offa’s Press

ISBN 978-1-7393618-6-0

£9.95

Unsung

Emma Purshouse

Offa’s Press

ISBN 978-1-7393618-6-0

£9.95

Divided into three distinct sections, this collection has a strong Black Country vibe and takes in a wide range of local historical characters plus a crown of sonnets referencing Shakespeare and – very importantly – Purshouse’s own distinctive celebrations of ‘ordinary’ people. These ‘unsung’ are central to the poet’s focus as she shines a light on their contribution to what gives her beloved home area its own particular special charm and verve.

This energy is evident in the opening poem – I mean, what a title! “Anne Hathaway finds sonnets written for another woman under the second-best bed and confronts William and his floozy on daytime television”! Borrowing language typical of the time, the poet screams abuse at the ‘other’ woman and we can almost visualise it in performance at Stratford itself.

After this outburst we are transported to a gentler scene voiced by a lion. The poem takes its inspiration from a painting of Daniel in the lion’s den, and is full of Purshouse’s renowned wit, with the lion announcing

I’d already eaten

so, you know, wasn’t interested in him.

Other poems in this first section are usefully annotated with footnotes about the many characters we may only know by name rather than by deed: John Wesley, St Giles, Catherine Eddowes, George Boden, Monika Singh Lee, William Matthews amongst them. There is also a poem about the un-named Matchgirls whose strike action of 1888 is said to have led to the formation of the Labour Party. Other topics include a response to a piece of taxidermy, some memories of a YTS girl and observations about a charity shop. The whole section urges the reader to notice the detail of important and not-so-important lives, all of which can have moments of significance, as exemplified by the way local people gave Queen Victoria

bands, bouquets, scrubbed-up children,

prayers

when she visited Wolverhampton.

Purshouse has fun with the fictional character of Little Nell created by Charles Dickens. The poem imagines the cheap souvenirs you might buy on a visit to the grave at St Bartholomew’s Church in Tong, near Wolverhampton. I’ve been myself and there really is a grave for Little Nell, no gift shop, but the idea there might have once been one is delicious. And the hotel, which was once a place for training the YTS girl, is now seen as the place where ‘200 asylum seekers [are] dumped’ – which brings us right up to modern times with the question ‘where is the humanity?’

The very moving poem “The best concert I ever went to” is set beside a death bed where, despite the presence of an oxygen machine, a woman (the poet’s mother?) sings until she is ‘spent’.

And I saw the slave past of both our houses

and I saw the joy and love

There are similar echoes in “And what would you have me sing?” where the poet is in a hospital where ‘Gaza flickers up on the ward TV’ and the patients ‘pray a silent prayer for peace.’

Now, I don’t know about you, but I think only a serious and committed poet with a real grasp of poetic craft would take on the challenge of writing a crown of sonnets. For anyone who isn’t familiar with this form, a crown of sonnets is a sequence which usually speaks to one character on a single theme; and the last line of each sonnet is echoed in the opening of the next. Purshouse’s sequence speaks of being flummoxed by Shakespeare as a teenager who asked bluntly ‘What’s this shit?’ The sonnets borrow brilliantly from Shakespeare’s linguistic style, blending it with Purshouse’s own, and they show her flair for adventurous witty writing. Clearly, she was a clever student curious to see why her teacher was so keen to push Shakespeare on them, but anxious not to be seen as a swot by her classmates. Eventually, ‘all that was so foul [became] so fair!’

The poet revels in the stories, the rhyme, the curses, even sees the deep relevance to her own life growing up in Thatcher’s Britain. Inspired to go to college, Purshouse gets a decent education and starts on the road to becoming the wonderful wordsmith she is today. ‘The power of words lifting from the page’ proved to be her salvation. This sequence is an eloquent celebration of the Bard and reminds us why we need to find inventive ways to keep him alive in our schools.

The final section of the book takes us right to the heart of what inspires Purshouse’s writing, the markets, streets, comings and goings of regular people, teenagers, shopkeepers, all of different heritage, all proud in their own way even when life isn’t easy. The poet notices everything, has such an eye for detail, for sights and sounds. She sees beauty amongst the grime of dirty towns in the margins,

And the wild weeds

crazed in July heat will sing their mad lullabies

to shadowy plane trees, ivy-clad red brick and dereliction

or

the vape stall plastic sheeting blows like a sail.

Pigeons peck at sludge.

The poet’s infectious passion for language and for understanding people enables her to draw us in until we feel things as deeply as she does. Whether she is taking us back through history, browsing artwork in a gallery, or watching folk from a park bench, Purshouse compels us to notice and remember. She gives a voice to the over-looked and under-appreciated and, boy, can she write.

Sep 30 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Emma Purshouse

Poetry review – UNSUNG: Pat Edwards admires Emma Purshouse’s skill in making poems from the stuff of everyday life

Divided into three distinct sections, this collection has a strong Black Country vibe and takes in a wide range of local historical characters plus a crown of sonnets referencing Shakespeare and – very importantly – Purshouse’s own distinctive celebrations of ‘ordinary’ people. These ‘unsung’ are central to the poet’s focus as she shines a light on their contribution to what gives her beloved home area its own particular special charm and verve.

This energy is evident in the opening poem – I mean, what a title! “Anne Hathaway finds sonnets written for another woman under the second-best bed and confronts William and his floozy on daytime television”! Borrowing language typical of the time, the poet screams abuse at the ‘other’ woman and we can almost visualise it in performance at Stratford itself.

After this outburst we are transported to a gentler scene voiced by a lion. The poem takes its inspiration from a painting of Daniel in the lion’s den, and is full of Purshouse’s renowned wit, with the lion announcing

Other poems in this first section are usefully annotated with footnotes about the many characters we may only know by name rather than by deed: John Wesley, St Giles, Catherine Eddowes, George Boden, Monika Singh Lee, William Matthews amongst them. There is also a poem about the un-named Matchgirls whose strike action of 1888 is said to have led to the formation of the Labour Party. Other topics include a response to a piece of taxidermy, some memories of a YTS girl and observations about a charity shop. The whole section urges the reader to notice the detail of important and not-so-important lives, all of which can have moments of significance, as exemplified by the way local people gave Queen Victoria

Purshouse has fun with the fictional character of Little Nell created by Charles Dickens. The poem imagines the cheap souvenirs you might buy on a visit to the grave at St Bartholomew’s Church in Tong, near Wolverhampton. I’ve been myself and there really is a grave for Little Nell, no gift shop, but the idea there might have once been one is delicious. And the hotel, which was once a place for training the YTS girl, is now seen as the place where ‘200 asylum seekers [are] dumped’ – which brings us right up to modern times with the question ‘where is the humanity?’

The very moving poem “The best concert I ever went to” is set beside a death bed where, despite the presence of an oxygen machine, a woman (the poet’s mother?) sings until she is ‘spent’.

There are similar echoes in “And what would you have me sing?” where the poet is in a hospital where ‘Gaza flickers up on the ward TV’ and the patients ‘pray a silent prayer for peace.’

Now, I don’t know about you, but I think only a serious and committed poet with a real grasp of poetic craft would take on the challenge of writing a crown of sonnets. For anyone who isn’t familiar with this form, a crown of sonnets is a sequence which usually speaks to one character on a single theme; and the last line of each sonnet is echoed in the opening of the next. Purshouse’s sequence speaks of being flummoxed by Shakespeare as a teenager who asked bluntly ‘What’s this shit?’ The sonnets borrow brilliantly from Shakespeare’s linguistic style, blending it with Purshouse’s own, and they show her flair for adventurous witty writing. Clearly, she was a clever student curious to see why her teacher was so keen to push Shakespeare on them, but anxious not to be seen as a swot by her classmates. Eventually, ‘all that was so foul [became] so fair!’

The poet revels in the stories, the rhyme, the curses, even sees the deep relevance to her own life growing up in Thatcher’s Britain. Inspired to go to college, Purshouse gets a decent education and starts on the road to becoming the wonderful wordsmith she is today. ‘The power of words lifting from the page’ proved to be her salvation. This sequence is an eloquent celebration of the Bard and reminds us why we need to find inventive ways to keep him alive in our schools.

The final section of the book takes us right to the heart of what inspires Purshouse’s writing, the markets, streets, comings and goings of regular people, teenagers, shopkeepers, all of different heritage, all proud in their own way even when life isn’t easy. The poet notices everything, has such an eye for detail, for sights and sounds. She sees beauty amongst the grime of dirty towns in the margins,

or

The poet’s infectious passion for language and for understanding people enables her to draw us in until we feel things as deeply as she does. Whether she is taking us back through history, browsing artwork in a gallery, or watching folk from a park bench, Purshouse compels us to notice and remember. She gives a voice to the over-looked and under-appreciated and, boy, can she write.