Poetry review – FRANK’S LUNCH SERVICE: Charles Rammelkamp appreciates the sheer physicality of the materials that make up this collection by Frank Rubino

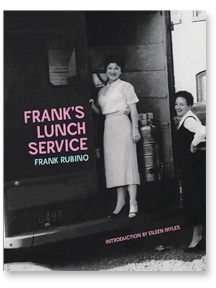

Frank’s Lunch Service

Frank Rubino

Lithic Press, 2025

ISBN: 978-1946-583-413

$20.00, 112 pages

Frank’s Lunch Service

Frank Rubino

Lithic Press, 2025

ISBN: 978-1946-583-413

$20.00, 112 pages

In her insightful introduction, Eileen Myles notes that a friend with whom she’d shared the manuscript had called Frank’s Lunch Service a “memoir,” but she takes issue with that characterization. ‘It’s family,’ she observes. ‘How can a person write such poems about their family?’ In this way, Frank’s Lunch Service, his father’s Newark, New Jersey, business, holds the collection together. It’s where the poet came to consciousness, in the love and trials of family. As Myles notes: ‘The entirety, his life and experience is metonymized by the store.’ Indeed, Rubino writes about the generations, his parents and grandparents, his siblings and children, uncles and aunts, all captured and summarized in the overarching image of Frank’s Lunch Service.

As Rubino concludes the poem, “The Dreadful Ghost of a Slaughtered Hog,” a poem about his father dying in hospice:

You realize how loved you are,

simply being a part

of the living world.

As with so many of Frank Rubino’s poems, his reflections begin with the introduction of a “thing” in the world. Here, it starts with his mother calling to ask: Do you want a ham? This prompts thoughts of animals used in experiments by pharmaceutical companies; the New Jersey company that patented Valium is one. He recounts the barbaric treatment of a chimp, Pepper. These experiments have nevertheless helped prolong his father’s life, but now he’s given just six weeks to live. He tells his son: ‘meat is meat,’ by which he means he knows he is dying.

Just as Rubino’s life is encapsulated in the business, so many of his reflections are jumpstarted by the consideration of random objects, “things,” like that ham. ‘I’m walking in town as I do, to be intimate with my memories,’ he begins the poem, “Use the microphone to create intimacy.” If there is a focus in the poem, it is an old dog named Rufus whom the poet remembers as he walks. Mainly, he’s pondering his purpose in the world, how he fits in (‘Like the master plan of working as a kid at Frank’s Lunch’). Crime, power, work: it’s all part of the equation, and then he recalls old Rufus, and he ponders their relationship. ‘Rufus came into my thoughts as I walked in town, intimate with my memories,’ the poem concludes.

Things? There are the basketball in “Called to Vitality,” the wood burner, in “Wood Burner,” the sweatshirt in “Sweatshirt Weather,” the classroom pencil sharpener, a black leather jacket, a footlocker, “Great Stuff” – a canned foam that expands – a whetstone, a rubber mallet, t-shirts, a helmet, in a poem about Colin Kaepernick and the Black Lives Matter movement. All of these mundane objects trigger his thoughts the way Frank’s Lunch itself defines his thinking. The siphon tube in “Siphon Tube,” is another object/poem that addresses his father’s cancer death: ‘he suffered with their tube in his side / like a Roman spear.’

It’s no coincidence that the poem immediately after “Siphon Tube” – in which a home hospice therapist explains ‘you could tell when the end comes, / because his feet would curl back, and it was true’ – comes a poem about Frank’s Lunch called “Early-early”:

I miss the crowds & the smell of food

cooking in Penn Station. It always reminded me

of the bacon frying and coffee

we made at Frank’s Lunch. Early-early.

Even if I’d never eat such things anymore,

they still smell good, and remind me of breakfast

when you’re roused at dawn and squeezed

down the cold throat of day.

This is the glue that holds the family together (‘time is the glue of suffering,’ he writes in “My kid confesses twenty years of crime”). To the extent that Frank’s Lunch Service can be considered a memoir, Rubino does allude to so many in his family. There’s his uncle, Richard, who died from AIDS. ‘Handsome, charming Richard, an actor,’ he calls him in “Abbey Road,” yet another object that focuses his memories, the iconic 1969 Beatles album (‘Poetry’s been my revolution / since I listened to side two of Abbey Road.’). There’s his brother, Billy, who packs a gun on his hip. ‘I wished he could shed the weight of the gun / he always wears beside him on his hip,’ Rubino writes in “I flew out to the pine green woods,” and in “pwee” he continues to meditate on his brother’s love of guns (‘pwee is the bullet sound.’).

Another brother (or is it the same one?), Tim, is also a “gun nut.” He features in “Jack belongs in the bottle, blood belongs in the veins,” “Big Shoots” and “The Hog of Circumstance.” He’s seen action in Afghanistan, suffers from PTSD (‘he slept alone on the sofa since Afghanistan’).

There’s also Rubino’s daughter, who takes center stage in “My kid confesses twenty years of crime,” “Kids who are young women, YWWAK,” “ Clover,” “I’m standing on a lot on Cambridge Road littered with the debris of a blown up house,” and “Rubber Mallet.” There’s his step-daughter in “Kong seems to be able to see my death” calling to talk with her mother.

There’s also his wife, Barbara, about whom he writes in “She came outside to write an article about lung cancer” and “You have been weighed in the balance,” which ends:

I felt her ribs rising and falling,

and heard the air coming in and out of her nose

like I hear you noodling your guitar down the hall,

playing your music, my son, after a long quiet year.

This is immediately followed by “I spoke with my son yesterday,” another father poem –

He needs a wall between you and him, always did.

He’s like a cat walking on a ledge.

“Sermon at New Years” may be the quintessential parent poem. It’s in the midst of the pandemic, and Rubino cautions:

Children, I’m a little scared of 2023.

As when my father would rouse me

for the day run at Frank’s Lunch Service in Newark,

I am called and shaken.

It always comes back to Frank’s Lunch Service, the touchstone of his experience, his metaphor for family. The collection concludes with “Sleeping, Waking, Dreaming,” in which he affirms ‘I don’t know where I am, but I am not lost.’

Life is this constant change, the unanticipated, the blindsiding circumstance, the where-did-that-come-from? The only certainty is the family, in all of its messy uncertainties – ergo, Frank’s Lunch Service.

Aug 28 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Frank Rubino

Poetry review – FRANK’S LUNCH SERVICE: Charles Rammelkamp appreciates the sheer physicality of the materials that make up this collection by Frank Rubino

In her insightful introduction, Eileen Myles notes that a friend with whom she’d shared the manuscript had called Frank’s Lunch Service a “memoir,” but she takes issue with that characterization. ‘It’s family,’ she observes. ‘How can a person write such poems about their family?’ In this way, Frank’s Lunch Service, his father’s Newark, New Jersey, business, holds the collection together. It’s where the poet came to consciousness, in the love and trials of family. As Myles notes: ‘The entirety, his life and experience is metonymized by the store.’ Indeed, Rubino writes about the generations, his parents and grandparents, his siblings and children, uncles and aunts, all captured and summarized in the overarching image of Frank’s Lunch Service.

As Rubino concludes the poem, “The Dreadful Ghost of a Slaughtered Hog,” a poem about his father dying in hospice:

You realize how loved you are, simply being a part of the living world.As with so many of Frank Rubino’s poems, his reflections begin with the introduction of a “thing” in the world. Here, it starts with his mother calling to ask: Do you want a ham? This prompts thoughts of animals used in experiments by pharmaceutical companies; the New Jersey company that patented Valium is one. He recounts the barbaric treatment of a chimp, Pepper. These experiments have nevertheless helped prolong his father’s life, but now he’s given just six weeks to live. He tells his son: ‘meat is meat,’ by which he means he knows he is dying.

Just as Rubino’s life is encapsulated in the business, so many of his reflections are jumpstarted by the consideration of random objects, “things,” like that ham. ‘I’m walking in town as I do, to be intimate with my memories,’ he begins the poem, “Use the microphone to create intimacy.” If there is a focus in the poem, it is an old dog named Rufus whom the poet remembers as he walks. Mainly, he’s pondering his purpose in the world, how he fits in (‘Like the master plan of working as a kid at Frank’s Lunch’). Crime, power, work: it’s all part of the equation, and then he recalls old Rufus, and he ponders their relationship. ‘Rufus came into my thoughts as I walked in town, intimate with my memories,’ the poem concludes.

Things? There are the basketball in “Called to Vitality,” the wood burner, in “Wood Burner,” the sweatshirt in “Sweatshirt Weather,” the classroom pencil sharpener, a black leather jacket, a footlocker, “Great Stuff” – a canned foam that expands – a whetstone, a rubber mallet, t-shirts, a helmet, in a poem about Colin Kaepernick and the Black Lives Matter movement. All of these mundane objects trigger his thoughts the way Frank’s Lunch itself defines his thinking. The siphon tube in “Siphon Tube,” is another object/poem that addresses his father’s cancer death: ‘he suffered with their tube in his side / like a Roman spear.’

It’s no coincidence that the poem immediately after “Siphon Tube” – in which a home hospice therapist explains ‘you could tell when the end comes, / because his feet would curl back, and it was true’ – comes a poem about Frank’s Lunch called “Early-early”:

This is the glue that holds the family together (‘time is the glue of suffering,’ he writes in “My kid confesses twenty years of crime”). To the extent that Frank’s Lunch Service can be considered a memoir, Rubino does allude to so many in his family. There’s his uncle, Richard, who died from AIDS. ‘Handsome, charming Richard, an actor,’ he calls him in “Abbey Road,” yet another object that focuses his memories, the iconic 1969 Beatles album (‘Poetry’s been my revolution / since I listened to side two of Abbey Road.’). There’s his brother, Billy, who packs a gun on his hip. ‘I wished he could shed the weight of the gun / he always wears beside him on his hip,’ Rubino writes in “I flew out to the pine green woods,” and in “pwee” he continues to meditate on his brother’s love of guns (‘pwee is the bullet sound.’).

Another brother (or is it the same one?), Tim, is also a “gun nut.” He features in “Jack belongs in the bottle, blood belongs in the veins,” “Big Shoots” and “The Hog of Circumstance.” He’s seen action in Afghanistan, suffers from PTSD (‘he slept alone on the sofa since Afghanistan’).

There’s also Rubino’s daughter, who takes center stage in “My kid confesses twenty years of crime,” “Kids who are young women, YWWAK,” “ Clover,” “I’m standing on a lot on Cambridge Road littered with the debris of a blown up house,” and “Rubber Mallet.” There’s his step-daughter in “Kong seems to be able to see my death” calling to talk with her mother.

There’s also his wife, Barbara, about whom he writes in “She came outside to write an article about lung cancer” and “You have been weighed in the balance,” which ends:

This is immediately followed by “I spoke with my son yesterday,” another father poem –

“Sermon at New Years” may be the quintessential parent poem. It’s in the midst of the pandemic, and Rubino cautions:

It always comes back to Frank’s Lunch Service, the touchstone of his experience, his metaphor for family. The collection concludes with “Sleeping, Waking, Dreaming,” in which he affirms ‘I don’t know where I am, but I am not lost.’

Life is this constant change, the unanticipated, the blindsiding circumstance, the where-did-that-come-from? The only certainty is the family, in all of its messy uncertainties – ergo, Frank’s Lunch Service.