Poetry review – AUGUST 24, 1957 : Charles Rammelkamp follows Robert Cooperman through recollections and reflections stirred by a traumatic childhood incident

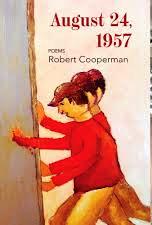

August 24, 1957

Robert Cooperman

Finishing Line Press, 2025

ISBN: 979-8-88838-938-6

$17.99 30 pages

August 24, 1957

Robert Cooperman

Finishing Line Press, 2025

ISBN: 979-8-88838-938-6

$17.99 30 pages

You see a book whose title is a date, and you know it’s one of those “before and after” milestones. Stephen King’s monumental novel, 11/22/63, weighing in at over 800 pages, is a case in point, dealing with the JFK assassination in Dallas. Or 9/11/2001, simply shortened to “Nine Eleven”: everybody knows it’s the World Trade Center and Pentagon terror attacks. In Robert Cooperman’s case, it’s something more personal but no less harrowing. It’s the day when, as an eleven-year-old boy, the poet experienced a bloody, life-threatening accident.

The title of the very first poem in the chapbook, “Shattered Glass,” emphasizes the trauma, with its echoes of Kristallnacht (“Night of Shattered Glass,” November 9, 1938), when Jewish businesses were destroyed in vicious anti-Semitic pogroms throughout Germany. Cooperman, who is Jewish, clearly chose the title to make the point. In the poem, the narrator and his wife are cleaning up a shattered glass table, sending him down a rabbit hole of memory to August 24, 1957.

Suddenly I was eleven again, running

into the apartment house vestibule,

one hand on the door frame,

the other shoving the glass

that gave from a hairline crack, blood

exploding, the odds I’d live not great.

Robert Cooperman has mined his childhood and youth in Brooklyn and New York City to produce many memorable collections, including Go Play Outside, about his youthful fascination with basketball; My Shtetl and The Words We Used, about growing up in a Jewish household and neighborhood in Brooklyn; City Hat Frame Factory, about his coming of age at the time his father ran a hat manufacturing business; Just Drive, about driving a taxi cab in New York as a young man. Even Their Wars, a tale of 1940s anti-Semitism in the American south, is based on his parents’ experience only a handful of years before he was born. And there is also That Summer, a collection of poems about a trip to England, during the summer of 1970. That adventure, we learn in “The Settlement,” was financed by the insurance payout.

Often Robert Cooperman’s poetry narratives are related in a variety of voices. His John Sprockett tales, for instance, the nineteenth century wild west badman, and his various reconsiderations of the Trojan War – Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea and Bearing the Body of Hector Home among them – consist of poems in the voices of dozens of characters. The two dozen poems that make up August 24, 1957, by contrast, are all in the voice of a single character, Cooperman himself.

The patient spends ten days in Brookdale Hospital – ‘to a kid of eleven, longer than Odysseus’s / years of wandering,’ he observes in the poem, “Blood.” That, of course, means ten days of institutional food – ‘revolting oatmeal, mac and cheese / resembling orange worms / ubiquitous Jell-o…’ Lucky for the lad his Aunt Roz smuggles in some more palatable food from Aaron’s Deli as recounted in the hilarious, “The Smuggled Pastrami Sandwich.”

Once he’s out of the hospital, the slow recovery and adjustment continue, as Cooperman writes in “Removing the Cast” and “Practicing Scales on a Neighbor’s Piano.” The doctor having advised the patient needed to start using his right hand, the injured paw ‘or forever forget I had one,’ he practices on their neighbor Mrs. Cohen’s piano.

I never attained basic competence,

let alone the spider dexterity

of Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis.

The only reason I kept returning?

Her daughter, Alice, two years older,

and maybe she’d be impressed, if

I’d played Beethoven’s “Fur Elise”

like the Maestro. So, I fumbled along.

The cast that mummified his arm and the sling that held his arm in place are other adjustments with which he contends. But as we learn in “One Good Thing,” at least he doesn’t have to play a particularly loathsome game called ‘Johnny on the Pony’ again which involves being hit with a rubber ball. His wrist is simply too weak.

Pardoned, I got to read,

looked up every now and then,

to see whose heinie

was getting walloped, grateful

my right hand was shriveled.

Less feeling than Captain Hook’s Hook.

And yes, there is a “before and after” perspective. In a poem with that title Cooperman laments that he will never be able to play handball again. Before? It was ‘so satisfying to smack a kill shot,’ but after? ‘I lamented I could never / be that master of strategy again.’

As the years go by, of course, the memory of the event loses its PTSD effect. Except for the reminder of the scar, it doesn’t always dent his consciousness. Still, just as the whole sequence began with a flashback decades later upon seeing a shattered glass patio tabletop, so the memory comes back every so often to haunt. As he observes at the end of “Dispensations,” the final poem in August 24, 1957:

Though every now and then, I glance

at my savaged wrist, and for a second or two,

I’m going through that glass door again,

my own little death, and not the delightful one.

Aug 25 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Robert Cooperman

Poetry review – AUGUST 24, 1957 : Charles Rammelkamp follows Robert Cooperman through recollections and reflections stirred by a traumatic childhood incident

You see a book whose title is a date, and you know it’s one of those “before and after” milestones. Stephen King’s monumental novel, 11/22/63, weighing in at over 800 pages, is a case in point, dealing with the JFK assassination in Dallas. Or 9/11/2001, simply shortened to “Nine Eleven”: everybody knows it’s the World Trade Center and Pentagon terror attacks. In Robert Cooperman’s case, it’s something more personal but no less harrowing. It’s the day when, as an eleven-year-old boy, the poet experienced a bloody, life-threatening accident.

The title of the very first poem in the chapbook, “Shattered Glass,” emphasizes the trauma, with its echoes of Kristallnacht (“Night of Shattered Glass,” November 9, 1938), when Jewish businesses were destroyed in vicious anti-Semitic pogroms throughout Germany. Cooperman, who is Jewish, clearly chose the title to make the point. In the poem, the narrator and his wife are cleaning up a shattered glass table, sending him down a rabbit hole of memory to August 24, 1957.

Robert Cooperman has mined his childhood and youth in Brooklyn and New York City to produce many memorable collections, including Go Play Outside, about his youthful fascination with basketball; My Shtetl and The Words We Used, about growing up in a Jewish household and neighborhood in Brooklyn; City Hat Frame Factory, about his coming of age at the time his father ran a hat manufacturing business; Just Drive, about driving a taxi cab in New York as a young man. Even Their Wars, a tale of 1940s anti-Semitism in the American south, is based on his parents’ experience only a handful of years before he was born. And there is also That Summer, a collection of poems about a trip to England, during the summer of 1970. That adventure, we learn in “The Settlement,” was financed by the insurance payout.

Often Robert Cooperman’s poetry narratives are related in a variety of voices. His John Sprockett tales, for instance, the nineteenth century wild west badman, and his various reconsiderations of the Trojan War – Lost on the Blood-Dark Sea and Bearing the Body of Hector Home among them – consist of poems in the voices of dozens of characters. The two dozen poems that make up August 24, 1957, by contrast, are all in the voice of a single character, Cooperman himself.

The patient spends ten days in Brookdale Hospital – ‘to a kid of eleven, longer than Odysseus’s / years of wandering,’ he observes in the poem, “Blood.” That, of course, means ten days of institutional food – ‘revolting oatmeal, mac and cheese / resembling orange worms / ubiquitous Jell-o…’ Lucky for the lad his Aunt Roz smuggles in some more palatable food from Aaron’s Deli as recounted in the hilarious, “The Smuggled Pastrami Sandwich.”

Once he’s out of the hospital, the slow recovery and adjustment continue, as Cooperman writes in “Removing the Cast” and “Practicing Scales on a Neighbor’s Piano.” The doctor having advised the patient needed to start using his right hand, the injured paw ‘or forever forget I had one,’ he practices on their neighbor Mrs. Cohen’s piano.

The cast that mummified his arm and the sling that held his arm in place are other adjustments with which he contends. But as we learn in “One Good Thing,” at least he doesn’t have to play a particularly loathsome game called ‘Johnny on the Pony’ again which involves being hit with a rubber ball. His wrist is simply too weak.

And yes, there is a “before and after” perspective. In a poem with that title Cooperman laments that he will never be able to play handball again. Before? It was ‘so satisfying to smack a kill shot,’ but after? ‘I lamented I could never / be that master of strategy again.’

As the years go by, of course, the memory of the event loses its PTSD effect. Except for the reminder of the scar, it doesn’t always dent his consciousness. Still, just as the whole sequence began with a flashback decades later upon seeing a shattered glass patio tabletop, so the memory comes back every so often to haunt. As he observes at the end of “Dispensations,” the final poem in August 24, 1957: