Poetry review – BLUE IN GREEN: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs enjoys the warm and gently upbeat tone of John Harvey’s latest chapbook

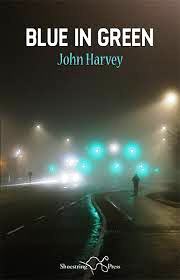

Blue in Green

John Harvey

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978 1 915553 70 6

£6

Blue in Green

John Harvey

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978 1 915553 70 6

£6

In his new chapbook collection John Harvey allows himself to savour each present moment, studying it with care and taking nothing for granted. Perhaps he is guided by something he has learned about painting:

The thing about still lifes, apparently,

is learning to measure the distance

between each object with the eye,

knowing instinctively the exact angle,

as if everything has fallen naturally into place.

Patient and measured observation is matched by Harvey’s descriptions of his own movements round a local neighbourhood of which he is clearly very fond

I make my way with special care

the sun bright

the paving stones uneven

He values his regular visits to a local café where ‘my coffee comes / without asking’ and where friends are as likely to talk about ‘the benefits of craniosacral therapy’ as to discourse on ‘the breakthrough he’s made / in his understanding of how to paint still lifes’.

Yet Harvey’s present, however precious, exists in the context of the past and sometimes the two come into sharp contrast. One morning, one of his many café friends asked if he ‘wanted to hold / her newborn son, scarcely a week old’; and as he did so he was painfully reminded that, only the day before, he had met an old friend from sixty years ago and learned that he and his wife were now ‘ beset by those ailments / that a too often come with age’. As Harvey ruefully observes

Sometimes life presents as a poem

plain & simple

The only task to set it down

clear and unfussed

as true as you can

Encounters with the past don’t always involve regret of course. There is often pleasure in continuity as in the recalling of a time long ago when

We walked from Little Italy

all the way back to East 49th Street.

You were my friend then

and you still are.

This ‘you’ is named as Kevin in the dedication of the poem “American Friend”. But a quite different ‘you’ also makes frequent appearances throughout the book, sometimes imagined with ‘a hand lifting to brush away / a stray hair’ or listened for expectantly as a ‘voice raised in greeting’ when ‘I turn the key in the lock’. And this is also the one of whom, at any moment, it is possible to ‘wonder how it was we came together / and how, against all odds, you have stayed.’ (Part of the answer to the first part of that question can be found in the poem “Leaving” which touches on the upheavals of moving house fairly late in life.)

“Leaving” also contains one of the book’s mentions of the pianist Keith Jarrett. This serves as a reminder that Harvey’s poems often portray him deeply engaged with music and in relative solitude (although the important ‘you’ is rarely very far away). As he listens to Shostakovich’s prelude & fugue in C major he notes that the music ‘moves in small steps/ as if anticipating rain’ and he relates this to the composer’s own forebodings about arrest by the NKVD

Listening each night for the booted step

upon the stairs, the knock on the door

By contrast, while listening to another Shostakovich piece, he is able to relax as if on a small boat as ‘the music tilts this way and that / away from the shore then back’.

Readers familiar with Harvey’s work who also expect quite a few jazz references will not be disappointed; and some may wish they had been with him at his local pub ‘listening to a tight little hard bop band / featuring a pianist with a great right hand’. A little more surprising however might be the dip into pop music of the 1960s as the basis of of the edgy concluding poem “Yellow Dress”.

There is a good deal of smiling contentment running through these poems but outright humour is in shorter supply. When it does appear it tends to be at the tongue-in-cheek expense of the poetry itself, for instance when Harvey describes his daughter charging him with once again ‘writing the same poem you’ve been writing now for years’. In this case he is able adroitly to sidestep the criticism by using a piece of arcane jazz knowledge; but a more sustained challenge comes from a recollected parental query

Surely you can’t just call yourself a poet my father said?

I was filling out a passport application at the time.

Surely there must be some kind of examination?

Harvey is able to mount a reasonable defence to this, but admits that in the end he ‘chickened out’ and simply put ‘writer’ as his occupation on the new passport. That indeed was, and still is, a valid claim since he is a successful author of crime novels and other fiction. But, in my view, this enjoyable book – along with his previous five collections – fully entitles him to employ the more specific and specialised title.

Sep 8 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – John Harvey

Poetry review – BLUE IN GREEN: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs enjoys the warm and gently upbeat tone of John Harvey’s latest chapbook

In his new chapbook collection John Harvey allows himself to savour each present moment, studying it with care and taking nothing for granted. Perhaps he is guided by something he has learned about painting:

Patient and measured observation is matched by Harvey’s descriptions of his own movements round a local neighbourhood of which he is clearly very fond

I make my way with special care the sun bright the paving stones unevenHe values his regular visits to a local café where ‘my coffee comes / without asking’ and where friends are as likely to talk about ‘the benefits of craniosacral therapy’ as to discourse on ‘the breakthrough he’s made / in his understanding of how to paint still lifes’.

Yet Harvey’s present, however precious, exists in the context of the past and sometimes the two come into sharp contrast. One morning, one of his many café friends asked if he ‘wanted to hold / her newborn son, scarcely a week old’; and as he did so he was painfully reminded that, only the day before, he had met an old friend from sixty years ago and learned that he and his wife were now ‘ beset by those ailments / that a too often come with age’. As Harvey ruefully observes

Encounters with the past don’t always involve regret of course. There is often pleasure in continuity as in the recalling of a time long ago when

This ‘you’ is named as Kevin in the dedication of the poem “American Friend”. But a quite different ‘you’ also makes frequent appearances throughout the book, sometimes imagined with ‘a hand lifting to brush away / a stray hair’ or listened for expectantly as a ‘voice raised in greeting’ when ‘I turn the key in the lock’. And this is also the one of whom, at any moment, it is possible to ‘wonder how it was we came together / and how, against all odds, you have stayed.’ (Part of the answer to the first part of that question can be found in the poem “Leaving” which touches on the upheavals of moving house fairly late in life.)

“Leaving” also contains one of the book’s mentions of the pianist Keith Jarrett. This serves as a reminder that Harvey’s poems often portray him deeply engaged with music and in relative solitude (although the important ‘you’ is rarely very far away). As he listens to Shostakovich’s prelude & fugue in C major he notes that the music ‘moves in small steps/ as if anticipating rain’ and he relates this to the composer’s own forebodings about arrest by the NKVD

By contrast, while listening to another Shostakovich piece, he is able to relax as if on a small boat as ‘the music tilts this way and that / away from the shore then back’.

Readers familiar with Harvey’s work who also expect quite a few jazz references will not be disappointed; and some may wish they had been with him at his local pub ‘listening to a tight little hard bop band / featuring a pianist with a great right hand’. A little more surprising however might be the dip into pop music of the 1960s as the basis of of the edgy concluding poem “Yellow Dress”.

There is a good deal of smiling contentment running through these poems but outright humour is in shorter supply. When it does appear it tends to be at the tongue-in-cheek expense of the poetry itself, for instance when Harvey describes his daughter charging him with once again ‘writing the same poem you’ve been writing now for years’. In this case he is able adroitly to sidestep the criticism by using a piece of arcane jazz knowledge; but a more sustained challenge comes from a recollected parental query

Harvey is able to mount a reasonable defence to this, but admits that in the end he ‘chickened out’ and simply put ‘writer’ as his occupation on the new passport. That indeed was, and still is, a valid claim since he is a successful author of crime novels and other fiction. But, in my view, this enjoyable book – along with his previous five collections – fully entitles him to employ the more specific and specialised title.