Poetry review – IN THE LILY ROOM: Nick Cooke admires Erica Hesketh’s collection about motherhood not only for being accomplished and moving but also for its broad appeal across gender boundaries

In The Lily Room

Erica Hesketh

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 978-1-916760-16-5

pp 90 £11.99

In The Lily Room

Erica Hesketh

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 978-1-916760-16-5

pp 90 £11.99

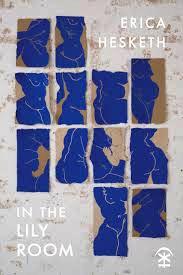

A meticulous account of childbirth and what can often follow it, Erica Hesketh’s debut collection, beautifully illustrated for Nine Arches by Laxmi Hussain, will both touch and haunt its readers, many of whom will be unfamiliar with the work of this poet and editor, originally from Denmark and Japan, now based in London.Although Clare Pollard has rightly observed that the book and its “leaky mess of new parenthood” is for mothers everywhere, I would add that it’s not for them exclusively. Hesketh has managed to present the intense and often conflicting emotions undergone by someone in early motherhood in ways that have universal appeal, regardless of gender and life experience.

We begin pre-birth, in ‘Tidings’, with a pointedly male doctor’s awkward humour that may or may not be intentional:

I am in the crimped air of the ultrasound clinic

ah yes, there is the vulva he says

As in some later poems, the scarcity of punctuation signals a dreamlike, stream-of-consciousness style that brings us closer to the woman at the centre of the incipient narrative, whose mind is wandering in a manner she perhaps couldn’t quite explain, though it may have to with lack of food and sleep:

she says: give me plums, give me figs, take that smell away

if I sit far enough away from the fridge

if I sing songs that make me cry on the sofa

child of mine, child of mine

But her attention is concentrated at the poem’s end, when the reality of what’s about to occur is succinctly brought home, as she is “ringed by curtains in the triage bay” and the orderlies come for her:

she says: mother, mother

we’re ready for you, they say

Is the soon-to-be-mother addressing herself, or calling for her own mother, by way of support and advice? The ambiguity is typical in a volume where the poet’s honesty extends to not offering pat answers to a number of actual or potential questions.

One question that receives no answer at all comes in the next poem, ‘Birth notes’, with the kind of self-assessment medical surveys constantly demand that patients make (“On a scale of one to ten / how confident do you feel?”). (We soon get the sense that her response would be on the lower side of the scale, overall.) Meanwhile, in what proves a truly remarkable account of childbirth, we witness the arrival of a midwife, and learn that a “gentle husband” is present. Our protagonist retains her sense of what’s unreassuringly going on not far away – “Emergency C-sections / bleating down the corridor” – and briefly channels her inner Miranda, as she pleads for a world that is not currently so brave, albeit new:

Beautiful moon:

show your face through this fearsome

tempest! Pity me –

On two knees, baring my teeth,

fingers white on the bedpost –

The great moment arrives, as the storm hits its height: “A cloudburst and she is here. / Whatever else happens, love”, where the final word seems both imperative and vocative.

For the rest of the story, she does everything in her power to obey that self-issued injunction, as she pours all the love she has into the “tree frog in my lap”, referred to as N. However, the book is also – indeed, largely – about the tribulations suffered by those suffering post-partum mental ill-health. Initially the issues centre on a feeling of inadequacy around breastfeeding, first observed in a fellow new mother: “Her nipples were like two black eyes / but she wouldn’t give up, she / needed this one thing” (‘Latch’). But this is far from all, as Hesketh – demonstrating an authoritative grip on a wide range of forms, including prose poems and an accomplished terza rima – skilfully documents a catalogue of challenges. These include the pressures of being constantly called “mummy”, and a sense of inescapable confinement, of having “brought the prison with us” (‘A Handsome Couple’), in her and her husband’s new circumstances.

‘Diagnosis’ encapsulates a range of powerful feelings, pointedly un-dreamlike, mainly around frustration, a fear of being patronised, and almost-blind panic:

please stop telling me how articulate I am

and do something I can’t

breathe in here

In notes at the end, Hesketh explains how a prose poem named ‘For the concerned spouse’ was inspired by the central deities in a Japanese creation myth, in which the mother dies in childbirth and descends into the underworld. Her speaker is often in a more modern form of hell, only partly relieved by meeting other young mothers at a community centre where confessions are made, such as “I’m terrified of hurting her | Is it wrong that I’m so bored?”, “while the rest of us nodded and sighed / like grasses along the sandbanks | of our childhood”.

The support group theme takes a half-horrifying, half-humorous twist in ‘Abecedary’, where an alphabetical succession of 26 mummies make key revelations, such as Vita’s, “who hasn’t gone out since the delivery – she’s waiting for the shadows to stop stalking her bedroom”. The next piece, ‘Boat’, sees paranoia reach its peak, with “the million ways / she will harm her baby taking turns / to run her through with bayonets”. Perhaps the most frightening of the million is the least violent, that “she would run / out of love and stall, exposed to the world / like a sailboat in a lull”.

But the collection would be overly dour if it focussed entirely on the negatives. The bittersweet nature of the whole experience is summarised in ‘Voice Note to Self’: “I couldn’t help but notice / how ravaged you are and yet / how utterly engrossed”. As the baby grows into a toddler, her mother’s tenderness for her grows to almost obsessive levels, while in ‘Sleep songs’ the desire to bequeath N “something better than rage, pain, anger and hate”, in Lou Reed’s immortal words, fills the mother with a new sense of purpose:

I would tie you to my trunk and start walking, begging

love to pull the goodness up through me,

gift you something better than this done-for planet.

This poem goes on to look back on the “awe and heartbreak” of N’s first days with sweeter memories than we have previously been given:

I would sit and wait for you to wake,

anxious for your tentacle fingers to reach up

and tell me you were ready to be held again.

The title poem, longlisted for the 2023 National Poetry Competition, evokes a time when N’s growing independence, and burgeoning imagination, bring her mother a new sense of perspective, with domestic orderliness well down the order of priorities: “After her bath she checks my hair for lions. / Dishes queue up by the sink.”

In ‘Tradition’, N’s first use of the word “Dadda” fills the mother’s heart not just with pride, but with belief in the future of a family that until then had hardly seemed to exist in her mind:

I’ve just recalled it – the certainty

that we three would go on

celebrating each other

like this, that this

would be what our family did,

what it meant.

And it’s with family that this unusually assured first collection ends, in ‘June’, with a new kind of dreamlike feel – cloudless, idyllic – banishing the earlier nightmares:

In the distance

Grandma waves from a bench,

impressed,

while at our daughter’s feet

we, giddy parents,

lie back on wind-whipped grass,

hands shading our eyes,

marvelling

at the blue,

feeling festive and delicious

Aug 17 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Erica Hesketh

Poetry review – IN THE LILY ROOM: Nick Cooke admires Erica Hesketh’s collection about motherhood not only for being accomplished and moving but also for its broad appeal across gender boundaries

A meticulous account of childbirth and what can often follow it, Erica Hesketh’s debut collection, beautifully illustrated for Nine Arches by Laxmi Hussain, will both touch and haunt its readers, many of whom will be unfamiliar with the work of this poet and editor, originally from Denmark and Japan, now based in London.Although Clare Pollard has rightly observed that the book and its “leaky mess of new parenthood” is for mothers everywhere, I would add that it’s not for them exclusively. Hesketh has managed to present the intense and often conflicting emotions undergone by someone in early motherhood in ways that have universal appeal, regardless of gender and life experience.

We begin pre-birth, in ‘Tidings’, with a pointedly male doctor’s awkward humour that may or may not be intentional:

As in some later poems, the scarcity of punctuation signals a dreamlike, stream-of-consciousness style that brings us closer to the woman at the centre of the incipient narrative, whose mind is wandering in a manner she perhaps couldn’t quite explain, though it may have to with lack of food and sleep:

But her attention is concentrated at the poem’s end, when the reality of what’s about to occur is succinctly brought home, as she is “ringed by curtains in the triage bay” and the orderlies come for her:

Is the soon-to-be-mother addressing herself, or calling for her own mother, by way of support and advice? The ambiguity is typical in a volume where the poet’s honesty extends to not offering pat answers to a number of actual or potential questions.

One question that receives no answer at all comes in the next poem, ‘Birth notes’, with the kind of self-assessment medical surveys constantly demand that patients make (“On a scale of one to ten / how confident do you feel?”). (We soon get the sense that her response would be on the lower side of the scale, overall.) Meanwhile, in what proves a truly remarkable account of childbirth, we witness the arrival of a midwife, and learn that a “gentle husband” is present. Our protagonist retains her sense of what’s unreassuringly going on not far away – “Emergency C-sections / bleating down the corridor” – and briefly channels her inner Miranda, as she pleads for a world that is not currently so brave, albeit new:

Beautiful moon: show your face through this fearsome tempest! Pity me – On two knees, baring my teeth, fingers white on the bedpost –The great moment arrives, as the storm hits its height: “A cloudburst and she is here. / Whatever else happens, love”, where the final word seems both imperative and vocative.

For the rest of the story, she does everything in her power to obey that self-issued injunction, as she pours all the love she has into the “tree frog in my lap”, referred to as N. However, the book is also – indeed, largely – about the tribulations suffered by those suffering post-partum mental ill-health. Initially the issues centre on a feeling of inadequacy around breastfeeding, first observed in a fellow new mother: “Her nipples were like two black eyes / but she wouldn’t give up, she / needed this one thing” (‘Latch’). But this is far from all, as Hesketh – demonstrating an authoritative grip on a wide range of forms, including prose poems and an accomplished terza rima – skilfully documents a catalogue of challenges. These include the pressures of being constantly called “mummy”, and a sense of inescapable confinement, of having “brought the prison with us” (‘A Handsome Couple’), in her and her husband’s new circumstances.

‘Diagnosis’ encapsulates a range of powerful feelings, pointedly un-dreamlike, mainly around frustration, a fear of being patronised, and almost-blind panic:

In notes at the end, Hesketh explains how a prose poem named ‘For the concerned spouse’ was inspired by the central deities in a Japanese creation myth, in which the mother dies in childbirth and descends into the underworld. Her speaker is often in a more modern form of hell, only partly relieved by meeting other young mothers at a community centre where confessions are made, such as “I’m terrified of hurting her | Is it wrong that I’m so bored?”, “while the rest of us nodded and sighed / like grasses along the sandbanks | of our childhood”.

The support group theme takes a half-horrifying, half-humorous twist in ‘Abecedary’, where an alphabetical succession of 26 mummies make key revelations, such as Vita’s, “who hasn’t gone out since the delivery – she’s waiting for the shadows to stop stalking her bedroom”. The next piece, ‘Boat’, sees paranoia reach its peak, with “the million ways / she will harm her baby taking turns / to run her through with bayonets”. Perhaps the most frightening of the million is the least violent, that “she would run / out of love and stall, exposed to the world / like a sailboat in a lull”.

But the collection would be overly dour if it focussed entirely on the negatives. The bittersweet nature of the whole experience is summarised in ‘Voice Note to Self’: “I couldn’t help but notice / how ravaged you are and yet / how utterly engrossed”. As the baby grows into a toddler, her mother’s tenderness for her grows to almost obsessive levels, while in ‘Sleep songs’ the desire to bequeath N “something better than rage, pain, anger and hate”, in Lou Reed’s immortal words, fills the mother with a new sense of purpose:

I would tie you to my trunk and start walking, begging love to pull the goodness up through me, gift you something better than this done-for planet.This poem goes on to look back on the “awe and heartbreak” of N’s first days with sweeter memories than we have previously been given:

I would sit and wait for you to wake, anxious for your tentacle fingers to reach up and tell me you were ready to be held again.The title poem, longlisted for the 2023 National Poetry Competition, evokes a time when N’s growing independence, and burgeoning imagination, bring her mother a new sense of perspective, with domestic orderliness well down the order of priorities: “After her bath she checks my hair for lions. / Dishes queue up by the sink.”

In ‘Tradition’, N’s first use of the word “Dadda” fills the mother’s heart not just with pride, but with belief in the future of a family that until then had hardly seemed to exist in her mind:

I’ve just recalled it – the certainty that we three would go on celebrating each other like this, that this would be what our family did, what it meant.And it’s with family that this unusually assured first collection ends, in ‘June’, with a new kind of dreamlike feel – cloudless, idyllic – banishing the earlier nightmares:

In the distance Grandma waves from a bench, impressed, while at our daughter’s feet we, giddy parents, lie back on wind-whipped grass, hands shading our eyes, marvelling at the blue, feeling festive and delicious