Poetry review – LANDSCAPES OF THE EXILED: Charles Rammelkamp commends Alan Catlin’s bleak poems as highly appropriate for the current troubled times

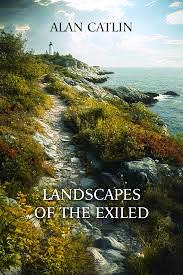

Landscapes of the Exiled

Alan Catlin

Dos Madres Press, 2025

ISBN: 978-1-962847-20-9

$21.00, 124 pages

Landscapes of the Exiled

Alan Catlin

Dos Madres Press, 2025

ISBN: 978-1-962847-20-9

$21.00, 124 pages

Nobody does Armageddon like Alan Catlin. His latest collection is divided into three parts: “Landscapes,” which takes place on a fictionalized Block Island, the tourist destination off the coast of Rhode Island; “Exiles,” a surrealistic landscape of its own, that feels mostly like the American southwest but any bleak location will do; and “Dark Comes Early in the Mountains,” a dreamscape in which the speaker mourns his lost muse Gladys. All three suites of poems add up to an apocalyptic vision, but it’s the longest, middle section, “Exiles,” that holds the collection together.

The protagonist of the poem “Fuelquest,” from the second section, may be the Virgil to the reader’s Dante as he guides us through the various “circles” of this particular hell.

“Just my luck,” you’re thinking,

“to run out of fuel in East Jesus.

Where the hell am I going to find

gas in a God forsaken place like

this?” You dig out your red and

yellow gas tank from amid the ruin

of the trunk and start walking down

the unlighted back road to nowhere,

pass the sign that says : WELCOME

TO EAST JESUS NO PEDDLERS

ALLOWED VIOLATERS WILL BE

SHOT ON SIGHT NO EXCEPTIONS

He then finds himself in a 42nd Street subway station, menacing Homeland Security dudes blocking his way, ready to freak out when suddenly a waitress at the Roswell Eat Here Diner offers him a menu. These are the elements of nightmare.

The world of “Exiles” is bleak and apocalyptic as only Alan Catlin can paint it. It’s filled with blasted neighborhoods full of hopeless people – the exiles. Most of the poems in this section are short, single-stanza verses depicting depraved or alarming scenes. “The Empty Window” begins:

She is throwing all the furniture

from a second story window, first,

an end table, followed by a lamp,

a transistor radio, still playing,

a large electric clock, cordless

telephones, the VCR.

Stuff is piling up on the sidewalk…

The poem “Next Door” begins ‘The women are beating / the dog with rubber / mallets…’ “Good Neighbor Policies” describes others fighting and pushing each other down flights of stairs; ‘you can hear their / children pleading “Don’t hit me, Mommy! / Daddy, please!” The unmuffled slapping….’ And the occupants of “The Old Soldier’s Home Before the Storm”?

They are propped up on the front porch,

confined to rocking chairs, held in place

by leather straps, their useless legs

covered by woolen shawls.

Earlier in the section, Catlin revisits other scenes of American shame. “The History of Industrialization,” “New Mexican Atomic Museum as Atrocity Exhibit” (‘costumed young virgins of / the desert riding high on smoke / spewing dummy bombs’ at the annual parade glorifying New Mexico’s history with the atomic bomb). “After the Fire, Desert Rock, Nevada, 1955,” tells of celebrated in newsreels hosted by the likes of John Cameron Swayze and Dave Garroway, the military experiments featuring human guinea pigs, though ‘Years later

inquiries about the toxic levels of rad exposures

are met with a bureaucratic shuffle, the modern

equivalent of lying. All records regarding that

particular field of endeavor were destroyed in

a warehouse fire in Kansas, thought the after-

effects linger in those hardy enough to have survived.

There are “The Dog Killers,” the “Sleepless Nights,” “Silent Spring,” with its echo of Rachel Carson. There are “Side Show Freaks” reminiscent of Diane Arbus. “Astronomers, Poets, Garbagemen” perform synonymous tasks, await similar fates. “The Woman with the White Plastic Watering Can Molded in the Shape of a Swan” summons scavenger birds that ‘descend around her, a feathering plague.’

In the “Landscape” poems that open the book, a couple, or a family (“We” is the protagonist of the poems) exist in a post-apocalyptic world, no less “exiled” on the island. As Catlin writes in the poem titled “Landscapes”:

It seemed unnatural

to grieve the end of landscapes

as no one responded to them

anymore

What would have been

the point

In “Dark Comes Early,” which starts the final section, ‘Gladys gave me a corkscrew once. / She insisted, “You never know when you might need one of those.”’ But she doesn’t say what for. And in the following poem, “Gladys always said,” she warns the speaker about ignoring dreams. When she dies in “After she left,” that’s when he understands why. In “Once the rain began,” the speaker tells us: ‘There was no place to go. Awake. Or dreaming.’ She haunts him. In “Just Before Dawn,” ‘I thought I saw Gladys dressed / in a Christmas pageant angel’s costume,’ and in “Overnight, while sleeping,” ‘I saw her face / in all the glass the hands of time used to hide behind.’ And again, in “Sometimes when I thought,” in that liminal world between sleep and wakefulness:

Sometimes when I thought I had been sleeping,

Gladys would whisper secrets in my ears.

These secrets are the sounds of night withheld,

and what their absence might suggest.

When I am fully awake, Gladys is gone

but the sound of her voice remains.

These characters are no less exiles than the couple in “Landscapes” or the freaks in “Exiles.” The speaker is caught in that world between consciousness and unconsciousness. The separate sections add up to more than their sum, as we say. Landscapes of the Exiled is a dark book for troubled times indeed.

Mar 21 2025

London Grip Poetry Review – Alan Catlin

Poetry review – LANDSCAPES OF THE EXILED: Charles Rammelkamp commends Alan Catlin’s bleak poems as highly appropriate for the current troubled times

Nobody does Armageddon like Alan Catlin. His latest collection is divided into three parts: “Landscapes,” which takes place on a fictionalized Block Island, the tourist destination off the coast of Rhode Island; “Exiles,” a surrealistic landscape of its own, that feels mostly like the American southwest but any bleak location will do; and “Dark Comes Early in the Mountains,” a dreamscape in which the speaker mourns his lost muse Gladys. All three suites of poems add up to an apocalyptic vision, but it’s the longest, middle section, “Exiles,” that holds the collection together.

The protagonist of the poem “Fuelquest,” from the second section, may be the Virgil to the reader’s Dante as he guides us through the various “circles” of this particular hell.

He then finds himself in a 42nd Street subway station, menacing Homeland Security dudes blocking his way, ready to freak out when suddenly a waitress at the Roswell Eat Here Diner offers him a menu. These are the elements of nightmare.

The world of “Exiles” is bleak and apocalyptic as only Alan Catlin can paint it. It’s filled with blasted neighborhoods full of hopeless people – the exiles. Most of the poems in this section are short, single-stanza verses depicting depraved or alarming scenes. “The Empty Window” begins:

She is throwing all the furniture from a second story window, first, an end table, followed by a lamp, a transistor radio, still playing, a large electric clock, cordless telephones, the VCR. Stuff is piling up on the sidewalk…The poem “Next Door” begins ‘The women are beating / the dog with rubber / mallets…’ “Good Neighbor Policies” describes others fighting and pushing each other down flights of stairs; ‘you can hear their / children pleading “Don’t hit me, Mommy! / Daddy, please!” The unmuffled slapping….’ And the occupants of “The Old Soldier’s Home Before the Storm”?

Earlier in the section, Catlin revisits other scenes of American shame. “The History of Industrialization,” “New Mexican Atomic Museum as Atrocity Exhibit” (‘costumed young virgins of / the desert riding high on smoke / spewing dummy bombs’ at the annual parade glorifying New Mexico’s history with the atomic bomb). “After the Fire, Desert Rock, Nevada, 1955,” tells of celebrated in newsreels hosted by the likes of John Cameron Swayze and Dave Garroway, the military experiments featuring human guinea pigs, though ‘Years later

There are “The Dog Killers,” the “Sleepless Nights,” “Silent Spring,” with its echo of Rachel Carson. There are “Side Show Freaks” reminiscent of Diane Arbus. “Astronomers, Poets, Garbagemen” perform synonymous tasks, await similar fates. “The Woman with the White Plastic Watering Can Molded in the Shape of a Swan” summons scavenger birds that ‘descend around her, a feathering plague.’

In the “Landscape” poems that open the book, a couple, or a family (“We” is the protagonist of the poems) exist in a post-apocalyptic world, no less “exiled” on the island. As Catlin writes in the poem titled “Landscapes”:

It seemed unnatural to grieve the end of landscapes as no one responded to them anymore What would have been the pointIn “Dark Comes Early,” which starts the final section, ‘Gladys gave me a corkscrew once. / She insisted, “You never know when you might need one of those.”’ But she doesn’t say what for. And in the following poem, “Gladys always said,” she warns the speaker about ignoring dreams. When she dies in “After she left,” that’s when he understands why. In “Once the rain began,” the speaker tells us: ‘There was no place to go. Awake. Or dreaming.’ She haunts him. In “Just Before Dawn,” ‘I thought I saw Gladys dressed / in a Christmas pageant angel’s costume,’ and in “Overnight, while sleeping,” ‘I saw her face / in all the glass the hands of time used to hide behind.’ And again, in “Sometimes when I thought,” in that liminal world between sleep and wakefulness:

These characters are no less exiles than the couple in “Landscapes” or the freaks in “Exiles.” The speaker is caught in that world between consciousness and unconsciousness. The separate sections add up to more than their sum, as we say. Landscapes of the Exiled is a dark book for troubled times indeed.