Poetry Review – Fothermather: Mat Riches gets a lot more out of Gail McConnell’s poetry than he might have expected at first

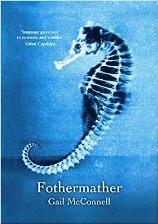

Fothermather

Gail McConnell

Ink Sweat & Tears Press

ISBN: 978-0992725341

32pp £7.50

Fothermather

Gail McConnell

Ink Sweat & Tears Press

ISBN: 978-0992725341

32pp £7.50

In the introduction to this collection McConnell talks about setting out to ‘examine non-biological queer parenthood…and how we might imagine parenting without gendering it so rigidly in name and form’, but that this all changed with arrival of Finn. Things shifted (and children do have a habit of changing your plans) to encompass a more playful look at language and naming; the naming of people and roles, the naming of parts and the words we use to do this with.

I was very grateful for this introduction because it helped me to pick up on some of the intent in the poems that I think I would otherwise have missed. Some of the poems benefit from the framing of the introduction because the book very much functions as a unit, in the sense that there are certain poems that, to my mind, would struggle to survive on their own outside the book’s family unit/y

The lack of clearly defined titles and disorientating formal construction of this (and some of the other poems) does make it tricky to get a sense of the poems when taken out of context of the collection as a whole. I’m not sure how I’d react to some of them if I found them in a magazine, but within the book it all works and fits.

I’m thinking of “light the seahorse”. I’m not saying for one second that it is an intrinsically bad poem – I very much enjoyed its playful form and the questions it asks about the nature of parenting when someone is the non-biological parent. That notion of not being fully one thing or another is seen in the form of the seahorse. As the poem has it, the seahorse has the ‘head of a horse’, ‘belly of a kangaroo’ and the ‘tail of a monkey’. You’ll have to read the book (and in case it’s not clear by the end of this review, I really think you should) to get a sense of the form at play here as these quotations are arranged in the shape of a seahorse when seen in situ in the book.

The seahorse idea continues in the poems that follow, in “when I see your spine” and “your shape is a letter”. The former poem begins

when I see your spine —when I see that,

yes, you have a spine! —

my mouth sounds

S

e

a

h

o

r

s

e

in the dark

gazing at the blackness of the screen

& at these flecks of white / of light / your bones

That yes, you have a spine suggests this is a response to seeing their baby – possibly for the first time – through a monitor, at a scan,

The sea and sea creatures are scattered throughout this collection, for example the shellfish of “Shell Notes”, a rearrangement of Francis Ponge’s, “Notes pour un cocquillage”. The poem, perhaps ironically, perhaps deliberately, stating that ‘Form is adapted from elsewhere (a residue / of that place it bears).’

Elsewhere, we meet the Cuttlefish—a creature renowned for being able to adapt its gender, or the way it displays its gender as discussed in the second stanza of “Cuttlefish”

The female seems standoffish.

The male looks down. He’ll re-

furbish the structure of him-

self, and take his boyish limbs

(his telltale eight) & (tucking)

make one pair vanish

& then approach

the one he wants, dragging

skin and sac and bone

by rippling his skirts–

skirts enclosing (in a double fold)

the ink bag, hearts and gills

and the anus usually not featured

in rhymes about God’s creatures.

Between that mention of cuttlefish anus and the irony mentioned earlier, there’s a lot of playfulness on display. Alongside this playfulness, and, for all of the questions provoked and raised by McConnell in Fothermather, what mustn’t be overlooked is that it sounds glorious, the commitment to sound of these poems is something that is to be enjoyed and admired.

Again, in her introduction, McConnell talks about growing ‘more curious about how sounds are made’ and also, while she’s talking about the evolution of the title of the book—describing it as a ‘nonsense word’, she also talks about playing with ‘its formative parts, sounding out syllable by syllable’, and I think this applies equally to the sounds of the poems in Fothermather.

“your shape is a letter” is rich in esses (s for Sea??), but the third stanza is abundant with the cee sound (all the seas!!!).

You understand that camouflage is custom, true

and changeable in circumstance, and that a name

obscures as much as it contains. O fish! O fish

with spine and neck. Born of choice and chance,

born of the male, a vertebrate upending expectation.

You’re a question mark reversed & beautifully embellished

In the title poem we see anagram variations of the title that are a joy to read out aloud. I’ll quote a few

Retort & tether

fort & moat

mar the ream

tear the tome

form a rath

From earth form O

at fathom three

a tar

— hear hear

mother mother

there for me?

That last one (although not the final line of the poem) is pretty powerful stuff, especially the question mark.

When I started reading this pamphlet, I wondered what I, a straight man and a biological parent, was going to get out of this book. The answer is a reminder that, as Donika Kelly points out in the blurb on the back, ‘the locus of parenting rests not at the fixed and gendered poles of mother and father but rather surfaces in an open sea that we must chart with intentionality. The connections McConnell’s speaker finds in these waters startle and astound with wit and the fulsomeness of love.’

And it’s that love that’s important. While they aren’t quoted anywhere in the book, and it does seem odd bringing them up now, but their name sake gets a few mentions, late 90’s band The Seahorses may have hit the nail on the head with their debut single ‘Love is the Law’. We’d do well to remember that.

May 5 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Gail McConnell

Poetry Review – Fothermather: Mat Riches gets a lot more out of Gail McConnell’s poetry than he might have expected at first

In the introduction to this collection McConnell talks about setting out to ‘examine non-biological queer parenthood…and how we might imagine parenting without gendering it so rigidly in name and form’, but that this all changed with arrival of Finn. Things shifted (and children do have a habit of changing your plans) to encompass a more playful look at language and naming; the naming of people and roles, the naming of parts and the words we use to do this with.

I was very grateful for this introduction because it helped me to pick up on some of the intent in the poems that I think I would otherwise have missed. Some of the poems benefit from the framing of the introduction because the book very much functions as a unit, in the sense that there are certain poems that, to my mind, would struggle to survive on their own outside the book’s family unit/y

The lack of clearly defined titles and disorientating formal construction of this (and some of the other poems) does make it tricky to get a sense of the poems when taken out of context of the collection as a whole. I’m not sure how I’d react to some of them if I found them in a magazine, but within the book it all works and fits.

I’m thinking of “light the seahorse”. I’m not saying for one second that it is an intrinsically bad poem – I very much enjoyed its playful form and the questions it asks about the nature of parenting when someone is the non-biological parent. That notion of not being fully one thing or another is seen in the form of the seahorse. As the poem has it, the seahorse has the ‘head of a horse’, ‘belly of a kangaroo’ and the ‘tail of a monkey’. You’ll have to read the book (and in case it’s not clear by the end of this review, I really think you should) to get a sense of the form at play here as these quotations are arranged in the shape of a seahorse when seen in situ in the book.

The seahorse idea continues in the poems that follow, in “when I see your spine” and “your shape is a letter”. The former poem begins

when I see your spine —when I see that, yes, you have a spine! — my mouth sounds S e a h o r s e in the dark gazing at the blackness of the screen & at these flecks of white / of light / your bonesThat yes, you have a spine suggests this is a response to seeing their baby – possibly for the first time – through a monitor, at a scan,

The sea and sea creatures are scattered throughout this collection, for example the shellfish of “Shell Notes”, a rearrangement of Francis Ponge’s, “Notes pour un cocquillage”. The poem, perhaps ironically, perhaps deliberately, stating that ‘Form is adapted from elsewhere (a residue / of that place it bears).’

Elsewhere, we meet the Cuttlefish—a creature renowned for being able to adapt its gender, or the way it displays its gender as discussed in the second stanza of “Cuttlefish”

Between that mention of cuttlefish anus and the irony mentioned earlier, there’s a lot of playfulness on display. Alongside this playfulness, and, for all of the questions provoked and raised by McConnell in Fothermather, what mustn’t be overlooked is that it sounds glorious, the commitment to sound of these poems is something that is to be enjoyed and admired.

Again, in her introduction, McConnell talks about growing ‘more curious about how sounds are made’ and also, while she’s talking about the evolution of the title of the book—describing it as a ‘nonsense word’, she also talks about playing with ‘its formative parts, sounding out syllable by syllable’, and I think this applies equally to the sounds of the poems in Fothermather.

“your shape is a letter” is rich in esses (s for Sea??), but the third stanza is abundant with the cee sound (all the seas!!!).

In the title poem we see anagram variations of the title that are a joy to read out aloud. I’ll quote a few

That last one (although not the final line of the poem) is pretty powerful stuff, especially the question mark.

When I started reading this pamphlet, I wondered what I, a straight man and a biological parent, was going to get out of this book. The answer is a reminder that, as Donika Kelly points out in the blurb on the back, ‘the locus of parenting rests not at the fixed and gendered poles of mother and father but rather surfaces in an open sea that we must chart with intentionality. The connections McConnell’s speaker finds in these waters startle and astound with wit and the fulsomeness of love.’

And it’s that love that’s important. While they aren’t quoted anywhere in the book, and it does seem odd bringing them up now, but their name sake gets a few mentions, late 90’s band The Seahorses may have hit the nail on the head with their debut single ‘Love is the Law’. We’d do well to remember that.