James Roderick Burns enjoys Judi Sutherland’s disciplined and penetrating poems

The Ship Owner’s House

Judi Sutherland

Vane Women Press

ISBN 9781904409199

£6.00

The Ship Owner’s House

Judi Sutherland

Vane Women Press

ISBN 9781904409199

£6.00

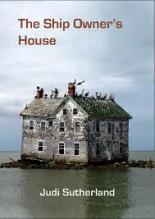

At just over thirty five pages, and 29 poems, The Ship Owner’s House has the feel and heft of a full collection rather than a pamphlet – the work is dense, focused (almost relentlessly so) and tightly arranged, with few soft passages and no poems making up the numbers; everything earns its place. The book is also beautifully produced. Using a clean colour scheme, and pleasing endpapers, it is complemented by a striking cover unusually relevant to the theme of the work: a splendidly rickety house, perched on a thin spar of land and festooned with a roof’s worth of seabirds, lists to an unlikely angle moments before sliding into the Chesapeake Bay.

If this fleeting image of fragility and dislocation wasn’t enough, the designer cheekily adds a Renaissance woodcut of a sea monster disappearing past the barcode on the back cover. Not quite Here Be Monsters, but certainly a reminder of the menace and instability lurking in everyday life. In this vein, and a short space, Sutherland achieves a remarkable meditation on the elusive, troubling nature of home.

It begins with a pair of resonant images – “I was neither church nor chapel … I had become work’s gypsy,/ like a wind-blown leaf” (‘When I was a stranger’) – and spreads out into almost every poem: the titular ship-owner’s house is “a galleon on an inland sea”, “ a foreign England; the stormfront edge / of nowhere”; the narrator of ‘Relocation’ laments “the place I thought was home turns out to be / somewhere we were passing through”; and almost the only image of surety – ‘The Coal-Jewel’, its “pent / primaeval energy, a trapped flame/left unburned, in a safe place” – is only safe because the poet has lifted it up for examination. Like everything else, it will soon be swallowed up, consumed or blown away.

These are not sad poems, or despairing in any way. They simply note the small accretions of feeling with each new location (or perhaps dislocation) that takes place in the poet’s life – the north east, her Scottish roots, the Pennines, London. Images of rootedness lost, the struggle to identify with a new place or circumstance, and inevitable departure pile up page after page, lending the whole volume a rich, melancholy air. It is captured best in a long central poem on perhaps the ultimate human displacement, figured in a drop from the surface down to the underground and what remains unseen, now brought back to life:

At night …

near Stockwell, where an engineer

holds a Tilley lamp – he died in 1950 –

and cowed monks prowl the Jubilee.

The old lady at Monument & Bank

vanishes through padlocked lattice gates.

There’s a faceless blonde at Beacontree;

and in Kennington Loop, the clunk of doors

being slammed along an empty train.

(‘Underworld’)

The poem ranges from the present, “the night shift” keeping “its silent hours”, back into the past and returns by way of shared trauma (the King’s Cross fire, terrorists with backpacks descending into the tunnels) to a different and contemporary ghost, “the shade of a young girl, seventeen / just arrived from Euston”. It revels in meticulous detail – heat lingering from the King’s Cross “flashover, fuelled by sweet wrappers / grease, dust, wooden escalators,/ rat – and human – hair” – as if to suggest we can best comprehend decades of jarring experience by bringing them close for inspection, but then turns in an unexpected direction. Our modern spectre, “swinging her weekend bag,/ running through Victoria”, is perhaps experiencing over and again the loss of a relationship, one whose other half has yet to fall:

Sometimes I see her saying goodbye

to a young man in a winter coat

as he exchanges all his gold for darkness.

It is an image both haunting and reassuring – exchanging gold for darkness cannot be good, but is also completely in tune with the movement of the rest of the book, which welcomes both light and dark as essential components of existence, and does its best to celebrate their interplay before the inevitable shift.

Sutherland’s use of telling detail is key to this cumulative effect. Sheep with “clean backs narrowed from shearing” crop, gambol and explore the fields before “that terrible night in August” when the lambs are “borne away, stumbling, to market” (‘Sheep in Midsummer’); in ‘For Jo Cox’ the MP’s murder is captured with chilling precision – “a death / that someone chooses for you / without permission, while all your future selves collapse / into a bullet hole”. The details are not always unsettling – I’m thinking of the delightful canal-side scene in ‘Milepost on the Trent & Mersey’, with its “deep wild green, this gloomy unflow / between square banks of ragged-robin fret/ox-eye and white willow” – but do insist on the here-and-now particularity of experience, which the larger tide of the book suggests might be all that is afforded us.

Overall, while there is the occasional off-note (unpaired poems on red kites, bells or Newcastle jammed too closely together), The Ship Owner’s House is a disciplined, penetrating study of what it means to be caught up in the slipstream of life. After every move, each new phase and dislocation, we return to the last line of the book’s opening: “every time / what was left behind was love and settlement”.

What more could we want from a tumbling, uncertain world than that?

Aug 9 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Judi Sutherland

James Roderick Burns enjoys Judi Sutherland’s disciplined and penetrating poems

At just over thirty five pages, and 29 poems, The Ship Owner’s House has the feel and heft of a full collection rather than a pamphlet – the work is dense, focused (almost relentlessly so) and tightly arranged, with few soft passages and no poems making up the numbers; everything earns its place. The book is also beautifully produced. Using a clean colour scheme, and pleasing endpapers, it is complemented by a striking cover unusually relevant to the theme of the work: a splendidly rickety house, perched on a thin spar of land and festooned with a roof’s worth of seabirds, lists to an unlikely angle moments before sliding into the Chesapeake Bay.

If this fleeting image of fragility and dislocation wasn’t enough, the designer cheekily adds a Renaissance woodcut of a sea monster disappearing past the barcode on the back cover. Not quite Here Be Monsters, but certainly a reminder of the menace and instability lurking in everyday life. In this vein, and a short space, Sutherland achieves a remarkable meditation on the elusive, troubling nature of home.

It begins with a pair of resonant images – “I was neither church nor chapel … I had become work’s gypsy,/ like a wind-blown leaf” (‘When I was a stranger’) – and spreads out into almost every poem: the titular ship-owner’s house is “a galleon on an inland sea”, “ a foreign England; the stormfront edge / of nowhere”; the narrator of ‘Relocation’ laments “the place I thought was home turns out to be / somewhere we were passing through”; and almost the only image of surety – ‘The Coal-Jewel’, its “pent / primaeval energy, a trapped flame/left unburned, in a safe place” – is only safe because the poet has lifted it up for examination. Like everything else, it will soon be swallowed up, consumed or blown away.

These are not sad poems, or despairing in any way. They simply note the small accretions of feeling with each new location (or perhaps dislocation) that takes place in the poet’s life – the north east, her Scottish roots, the Pennines, London. Images of rootedness lost, the struggle to identify with a new place or circumstance, and inevitable departure pile up page after page, lending the whole volume a rich, melancholy air. It is captured best in a long central poem on perhaps the ultimate human displacement, figured in a drop from the surface down to the underground and what remains unseen, now brought back to life:

At night … near Stockwell, where an engineer holds a Tilley lamp – he died in 1950 – and cowed monks prowl the Jubilee. The old lady at Monument & Bank vanishes through padlocked lattice gates. There’s a faceless blonde at Beacontree; and in Kennington Loop, the clunk of doors being slammed along an empty train. (‘Underworld’)The poem ranges from the present, “the night shift” keeping “its silent hours”, back into the past and returns by way of shared trauma (the King’s Cross fire, terrorists with backpacks descending into the tunnels) to a different and contemporary ghost, “the shade of a young girl, seventeen / just arrived from Euston”. It revels in meticulous detail – heat lingering from the King’s Cross “flashover, fuelled by sweet wrappers / grease, dust, wooden escalators,/ rat – and human – hair” – as if to suggest we can best comprehend decades of jarring experience by bringing them close for inspection, but then turns in an unexpected direction. Our modern spectre, “swinging her weekend bag,/ running through Victoria”, is perhaps experiencing over and again the loss of a relationship, one whose other half has yet to fall:

It is an image both haunting and reassuring – exchanging gold for darkness cannot be good, but is also completely in tune with the movement of the rest of the book, which welcomes both light and dark as essential components of existence, and does its best to celebrate their interplay before the inevitable shift.

Sutherland’s use of telling detail is key to this cumulative effect. Sheep with “clean backs narrowed from shearing” crop, gambol and explore the fields before “that terrible night in August” when the lambs are “borne away, stumbling, to market” (‘Sheep in Midsummer’); in ‘For Jo Cox’ the MP’s murder is captured with chilling precision – “a death / that someone chooses for you / without permission, while all your future selves collapse / into a bullet hole”. The details are not always unsettling – I’m thinking of the delightful canal-side scene in ‘Milepost on the Trent & Mersey’, with its “deep wild green, this gloomy unflow / between square banks of ragged-robin fret/ox-eye and white willow” – but do insist on the here-and-now particularity of experience, which the larger tide of the book suggests might be all that is afforded us.

Overall, while there is the occasional off-note (unpaired poems on red kites, bells or Newcastle jammed too closely together), The Ship Owner’s House is a disciplined, penetrating study of what it means to be caught up in the slipstream of life. After every move, each new phase and dislocation, we return to the last line of the book’s opening: “every time / what was left behind was love and settlement”.

What more could we want from a tumbling, uncertain world than that?

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, James Roderick Burns, poetry