Alex Josephy finds authentic voices in Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s poems of theatrical nostalgia

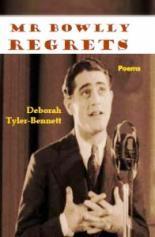

Mr Bowlly Regrets

Deborah Tyler-Bennett

The King’s England Press

ISBN 978 1 909548 69 5

£7.95

Mr Bowlly Regrets

Deborah Tyler-Bennett

The King’s England Press

ISBN 978 1 909548 69 5

£7.95

I was very glad to come upon Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s collection. The slightly eccentric typefaces and layout caught my eye immediately; there’s something unusually approachable about the look of the book, something jaunty and refusing to take itself too seriously. Then there’s the way one poem follows another, occasionally sharing a page as though they need to keep coming without too much of a pause. I was perhaps sceptical, yet ready to accept the first poem’s invitation to ‘tune in today’.

Derived from and revelling unashamedly in images and textures of the past, paradoxically these poems are a breath of fresh air. The King’s England Press seems an appropriate publishing house for poems located so firmly in England and versions of Englishness. A central strength is Tyler-Bennett’s powerful and precise sense of place and time. Clothes and appearances are meticulously described; at times the experience of reading the book is like opening a very well-stocked dressing-up box. Images that have stayed with me include a woman’s skin “a make-up man’s milk-white, almost blue as blackbird eggs; a male sea of moustaches, brilliantine”; and lace made by the calloused hands of Mansfield workers:

delicacy free-

falling, a spider’s thread of imitation lily,

wide-mouthed peony, moss; or beaded-

vermicelli’s lugworm casts.

The surprise in all this enjoyable retro sartorial detail is the way in which human vulnerabilities are revealed, as in these lines from ‘Ice Cream’:

Fondant-centred Arthur Seaton, bird-boned

through Ted jacket as we hugged goodbye

for what might be the last time, but it wasn’t…

The poet’s elliptical expression is striking right from the start; a kind of skipping gait composed of partial sentences and words left unsaid, as though she is constantly wanting to cut to the chase or to pursue a fast flow of treasured stories and observations. It carries us into a world of remembered narratives and often exuberant characters,. In the first poem in the collection we encounter the “lemon-drop perfection” of Mr Bowlly’s crooning, and are conveyed rapidly to his unfortunate wartime demise:

Fateful decision, returning to his flat,

slaughtered by a falling door.

As in other poems here, the tone hovers between elegy and comedy. I very much liked the way this poet is not afraid to record the sentimental gestures that often express or accompany genuine emotion. Never condescending, she mourns a world that is passing, but is always ready to surprise the reader with a chuckle or a choice moment of absurdity: the found poetry of a bingo holiday blurb, naff publicity churned out for the heritage industry.

In ‘Impossible Journeys’, Tyler-Bennett’s happy ear for local vernacular combines to good effect with her avoidance of the “little words”, adding to the witty tone and allowing for a swift journey into the changing experience of life in the East Midlands, where many of the poems are set.

‘Not what it were,’ Gran’s com-plaint, till-door shut,

hardware shop now Takeaway Chinese,

(pungent putty to menu’s number three).

Tyler-Bennett excels at portraiture. She pays homage to, among others, lace workers, miners and World War 1 soldiers, often deftly contrasting their workaday lives with starry aspirations and longings. I particularly enjoyed the woman who “ought to be in pictures”, the “silk scarf’s shift around the neck” suggesting a whole world of feminine detail. The poem ends with a touching vignette of her “small parents” in their “stippled wren house, not for peacocks”, described as “chestnut-faced deer surprised – producing a gazelle”.

These are affectionate poems, bearing witness and paying tribute to the histories of ‘ordinary’ working people, their lives and their icons. In many of them it’s the accretion of specifics – names, places – that moves the poem into a wider sphere of meaning. They speak of a disappearing culture. There are closed-down factories, graveyards, the known and unknown dead (“Doris Brown. Neat stone could be encircled with both hands”). Many of the characters are recalled larger-than-life, through a child’s eyes, as in ‘Mansfield’s Mae West’, a portrait of a landlady who

ruled her pub

bare-knuckle fist in violet velvet glove,

or more poignantly in ‘Bigger’:

Tommy Atkins, silhouette at ceme-tery gates seems jockey

sized. Was once, we knew the bigger man.

The book is organised thematically, with sections on Mansfield, a writing residency focussed on a First World War project, a Brighton section, and finally ‘Books, Films and Telly.’ I’m not sure that this always works to best advantage; the last part in particular might have come across more interestingly if integrated into the book as a whole. As it is, the themes of successive poems in this section start to seem a little predictable, which is a pity as there are amusing and touching pieces, for instance a found poem on Charles Dickens tourism, reflections on the pretension of a pet cemetery (“inscriptions craftsmen-carved from local rock”) as opposed to the injustice of other human deaths treated without respect (“baby in home-made box placed/in the grave of someone better-off”), and an update of ‘An Inspector Calls’ with reference to austerity Britain.

This book is by no means just an enjoyable retro ride; Tyler-Bennett also turns her attention toward contemporary injustices. In ‘Faulty’, a poignant, ragged sonnet, she juxtaposes a homeless “gently-spoken boy” with a theatrical comedy poster; “crazy worlds turned upside-down”.

The Brighton poems are written with a particular sense of brio; of the Hydro Hotel:

I could pen this place love notes for still existing

with unapolagetic Tudorbethan heartbeat.

A sonnet celebrating ‘Brighton’s Music Hall’ sparkles with the fun of rhyme; I was won over by the camp surface glamour: “glit-tery/chattery/latterly/skitter”. And Dusty (Springfield, of course) providing the “sobbing vocals” to mourn and memorialise lives and life-styles lost.

Clearly, the poems from the World War One residency (‘Books of the Village’) belong together. I thought some of these more achieved than others, but admired the way the poet has found fresh ways to convey ‘the pity of war’. Again it was the relationship between people and place – and the displacements caused by war – that moved me the most, for instance the devastating ending to ’No Relation’, an elegy to a farm hand killed right at the end of the war:

death ringing in a week before peace bells sounded

across changed fields his boy, Sid, had sewn,

Diseworth to Kegworth, Bleak House to Finger Farm.

In ‘Them’, the narrator, trying to describe her great grandparents as portrayed in the sepia photo, comments:

Wish I was in the business of restoring voices.

Actually, I think she is. This is a collection I’ll return to, and Tyler-Bennett is a poet I would love to hear on stage. The poems are full of authentic voices pleading to be read aloud.

Alex Josephy finds authentic voices in Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s poems of theatrical nostalgia

I was very glad to come upon Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s collection. The slightly eccentric typefaces and layout caught my eye immediately; there’s something unusually approachable about the look of the book, something jaunty and refusing to take itself too seriously. Then there’s the way one poem follows another, occasionally sharing a page as though they need to keep coming without too much of a pause. I was perhaps sceptical, yet ready to accept the first poem’s invitation to ‘tune in today’.

Derived from and revelling unashamedly in images and textures of the past, paradoxically these poems are a breath of fresh air. The King’s England Press seems an appropriate publishing house for poems located so firmly in England and versions of Englishness. A central strength is Tyler-Bennett’s powerful and precise sense of place and time. Clothes and appearances are meticulously described; at times the experience of reading the book is like opening a very well-stocked dressing-up box. Images that have stayed with me include a woman’s skin “a make-up man’s milk-white, almost blue as blackbird eggs; a male sea of moustaches, brilliantine”; and lace made by the calloused hands of Mansfield workers:

The surprise in all this enjoyable retro sartorial detail is the way in which human vulnerabilities are revealed, as in these lines from ‘Ice Cream’:

The poet’s elliptical expression is striking right from the start; a kind of skipping gait composed of partial sentences and words left unsaid, as though she is constantly wanting to cut to the chase or to pursue a fast flow of treasured stories and observations. It carries us into a world of remembered narratives and often exuberant characters,. In the first poem in the collection we encounter the “lemon-drop perfection” of Mr Bowlly’s crooning, and are conveyed rapidly to his unfortunate wartime demise:

As in other poems here, the tone hovers between elegy and comedy. I very much liked the way this poet is not afraid to record the sentimental gestures that often express or accompany genuine emotion. Never condescending, she mourns a world that is passing, but is always ready to surprise the reader with a chuckle or a choice moment of absurdity: the found poetry of a bingo holiday blurb, naff publicity churned out for the heritage industry.

In ‘Impossible Journeys’, Tyler-Bennett’s happy ear for local vernacular combines to good effect with her avoidance of the “little words”, adding to the witty tone and allowing for a swift journey into the changing experience of life in the East Midlands, where many of the poems are set.

Tyler-Bennett excels at portraiture. She pays homage to, among others, lace workers, miners and World War 1 soldiers, often deftly contrasting their workaday lives with starry aspirations and longings. I particularly enjoyed the woman who “ought to be in pictures”, the “silk scarf’s shift around the neck” suggesting a whole world of feminine detail. The poem ends with a touching vignette of her “small parents” in their “stippled wren house, not for peacocks”, described as “chestnut-faced deer surprised – producing a gazelle”.

These are affectionate poems, bearing witness and paying tribute to the histories of ‘ordinary’ working people, their lives and their icons. In many of them it’s the accretion of specifics – names, places – that moves the poem into a wider sphere of meaning. They speak of a disappearing culture. There are closed-down factories, graveyards, the known and unknown dead (“Doris Brown. Neat stone could be encircled with both hands”). Many of the characters are recalled larger-than-life, through a child’s eyes, as in ‘Mansfield’s Mae West’, a portrait of a landlady who

or more poignantly in ‘Bigger’:

The book is organised thematically, with sections on Mansfield, a writing residency focussed on a First World War project, a Brighton section, and finally ‘Books, Films and Telly.’ I’m not sure that this always works to best advantage; the last part in particular might have come across more interestingly if integrated into the book as a whole. As it is, the themes of successive poems in this section start to seem a little predictable, which is a pity as there are amusing and touching pieces, for instance a found poem on Charles Dickens tourism, reflections on the pretension of a pet cemetery (“inscriptions craftsmen-carved from local rock”) as opposed to the injustice of other human deaths treated without respect (“baby in home-made box placed/in the grave of someone better-off”), and an update of ‘An Inspector Calls’ with reference to austerity Britain.

This book is by no means just an enjoyable retro ride; Tyler-Bennett also turns her attention toward contemporary injustices. In ‘Faulty’, a poignant, ragged sonnet, she juxtaposes a homeless “gently-spoken boy” with a theatrical comedy poster; “crazy worlds turned upside-down”.

The Brighton poems are written with a particular sense of brio; of the Hydro Hotel:

A sonnet celebrating ‘Brighton’s Music Hall’ sparkles with the fun of rhyme; I was won over by the camp surface glamour: “glit-tery/chattery/latterly/skitter”. And Dusty (Springfield, of course) providing the “sobbing vocals” to mourn and memorialise lives and life-styles lost.

Clearly, the poems from the World War One residency (‘Books of the Village’) belong together. I thought some of these more achieved than others, but admired the way the poet has found fresh ways to convey ‘the pity of war’. Again it was the relationship between people and place – and the displacements caused by war – that moved me the most, for instance the devastating ending to ’No Relation’, an elegy to a farm hand killed right at the end of the war:

In ‘Them’, the narrator, trying to describe her great grandparents as portrayed in the sepia photo, comments:

Actually, I think she is. This is a collection I’ll return to, and Tyler-Bennett is a poet I would love to hear on stage. The poems are full of authentic voices pleading to be read aloud.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: Alex Josephy, books, poetry