Nick Cooke finds that Angela Readman’s new collection lives up to the description given on the book jacket

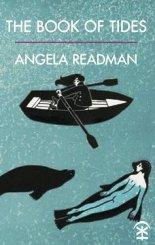

The Book of Tides

Angela Readman

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 9781911027102

67 pp £9.99

The Book of Tides

Angela Readman

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 9781911027102

67 pp £9.99

A critic quoted on the book jacket takes the normally inadvisable course of employing the term ‘phantasmagorical’ to describe the world created in this collection, Angela Readman’s third. Although I might have winced before I turned the first page, I nodded with a wistful smile after completing the last. It’s a book which does indeed, to cite one dictionary’s definition of that Disney-sounding epithet, give us “a shifting series of phantasms, illusions, or deceptive appearances, as in a dream or as created by the imagination”.

This slippery, shimmering quality might imply an intangibility, even a vagueness, at odds with the more muscular diction and outlook which some readers, consciously or otherwise, have been trained to regard as optimal, whether the poet is a man or a woman. However, in counterpoint, that to my mind confirms this books’s true quality; further exploration uncovers a hard-bitten and often knotty core, which has much to do with its far from dreamy setting, in a timeless fishing community where both men and women work gnarled fingers to their doubtless hardily constructed bones.

The very first words of the title – and opening – poem conjure up a finger-clicking transformation suggestive of magic, perhaps even witchcraft:

Like that, the old lass could switch into a ship’s mast,

stood on that cliff, air wringing a swell of hips

out of her skirt. Then, she was Ma again….

“Old lass”, ostensibly a term of colloquial endearment, is in reality a deft oxymoron underpinning the key theme of transience at its most scarily swift. The skilful personalisation introducing the speaker’s mother emphasises rapidity of another sort – the way the imagination can splice stories, characters, whole worlds, time-zones, modes of perception together in less than an eye-blink. In the next line the journey backwards takes on a lexical aspect: “….dragging me through the plothery snicket”. As if to reinforce the significance of speed, Readman has said in an interview that these dialect words from her childhood came to her very quickly while writing the poem, even though she hadn’t thought about them in decades. Men then make what turns out to be a typically brief and largely functional, horny-handed appearance –

Fishermen knocked, bags of whelks at the door,

trout like rainbows dandled in raw hands –

with that second line encapsulating the dual presence of the ephemeral and the almost painfuly concrete, before the camera turns back to its main point of focus. In other poems a woman’s apparent lack of control over her own identity may seem a weakness – ‘The Morning of La Llorona’, for example, memorably ends “And I rushed to your house, a waterfall, ready / to pour whoever I thought I was into your arms.” But in ‘The Book of Tides’ the matriarchically primed woman’s particular take on ‘not knowing her own strength’ links her power with its own unknown-ness. The Lawrentian use of “inchoate” comes to mind here, as do various episodes from the Odyssey:

I did not know if I’d live

my magic too, if I’d ever cut through the bluster

and blow in an ear to know when to will

a man home or wreck him en route.

In ‘Radiography’, a similar sense of unsureness paradoxically gives a wide-eyed acuity and luminosity of perception to the results of an X-ray on the speaker’s mother:

I didn’t know

inside her would look so beautiful,

cool as spilled ink, a cyanotype of years,

those shadows in her head the shape

of a polar bear sniffing an evening,

nosing through the ice.

Readman’s stance, if that word can be used in relation to an authorial overview of such deliberate fluidity, is feminist in the broadest and most unpresumptuous sense, in that it does not seek to downgrade a woman’s right to choose a traditionally domestic way of life. The steadfast wife in ‘The Woman Who Could Not Say Love’ expresses her love through darning holes in her fisherman husband’s clothes: “Let a stitch / in a frayed pocket proclaim / what thinking of him is.” The poet’s bravely unmodish attitude goes hand in hand with a willingness to accept without judgment, even to celebrate, what might be looked on as “old wives’ tales”. In the case of ‘The Sound of a Knot Being Untied’, this becomes old husbands’ tales, at least if one interprets the poem’s footnote literally: “Fishermen once held the superstition that some women could prevent storms by tying knots in a handkerchief, such handkerchiefs were carried for safe voyage.”

The poem itself is rather more about the recurring theme of watery transience, and stitching time rather than cloth. Once again the key idea is couched in hedging terms, modality and surmise rather than the pretence of fact, and once again we see the characteristic combination of fragile and transient (“raindrops”) with solid and grounded (“anchored a collarbone”):

You may wonder when being naked stopped

being as simple as catching a woman bathe

– raindrops hung on the line as water rolled,

anchored a collarbone to a pulse.

That anchor is of course a crucial metaphor, but in effect it’s a signifier without a signified: the fisherman’s one dependable protection against the power of water finds no analogue when it comes to time. However, there is a positive, if ambivalent slant. Having begun “Look to your lasses, lads, if you can”, the poem ends with an exhortation that both admits the unstoppable march of time and reminds us of the few but real consolations in this swiftly-passing life, with “if” transmuted, by the magic of optimism, to “while”, even as the patriarchal illusion of permanent sexual/contractual possession evaporates with “your” becoming “that”: “Look to that lass, now, / open a mouthful of sorrys, kiss her while you can.” The feminist angle here is all the more articulate for being so obliquely noted.

Other delights include the way Readman, however sophisticated in other areas, does not eschew some of the more basic tools in the poet’s armoury, particularly internal rhyme, assonance and alliteration, in which the book abounds. All of the above emerge in this quasi-Hopkinsian snippet from ‘The Morning of La Llorona’: “I killed / a kingfisher, sliced light off its back to fill gaps”. Among the countless alliterative instances, she has a true penchant for sibilance, as in the prose poem ‘Featherweight’ – “Boys who got too close snapped, spines skinny rushes whistling in the wind” – and ‘The House that Wanted to be a Boat’, which focusses on a cliffside cottage slipping into the sea through coastal erosion:

Yet it slides slowly, glacial

pools of one man’s fingertips glossed

into skirting boards hold it back. Strands

of his hair fasten floorboards that keel

for our losses.

This sense of resistance (“slowly” here implies “defiantly”) even in the face of unstoppable forces is for me the collection’s keynote, one captured perfectly in the poem which moved me most of all, ‘To Kill a Robin’, where another fishing superstition – “If you kill a robin on New Year’s Day, / give a feather to a rodman and he’ll always sail clear” – leads the poem’s speaker, or rather herself as a child, to apply the dictum in earnest, only to find the supposedly powerless victim resisting her to the last. Significantly, while we are given flashes of undreamlike physicality (“the hunch of me / hunkered”, “nithered fingers”, “cave of my grasp”), water, that eternal symbol of evanescence, finds its way into the final line, just as it seeps into almost every page of this haunting and splendidly judged collection:

I caught the robin

in nithered fingers I barely dared open. There,

the bird perfectly refused to have its neck snapped.

It simply stopped in the cave of my grasp, one

last trill like water rolling a silence over my hands.

Nick Cooke finds that Angela Readman’s new collection lives up to the description given on the book jacket

A critic quoted on the book jacket takes the normally inadvisable course of employing the term ‘phantasmagorical’ to describe the world created in this collection, Angela Readman’s third. Although I might have winced before I turned the first page, I nodded with a wistful smile after completing the last. It’s a book which does indeed, to cite one dictionary’s definition of that Disney-sounding epithet, give us “a shifting series of phantasms, illusions, or deceptive appearances, as in a dream or as created by the imagination”.

This slippery, shimmering quality might imply an intangibility, even a vagueness, at odds with the more muscular diction and outlook which some readers, consciously or otherwise, have been trained to regard as optimal, whether the poet is a man or a woman. However, in counterpoint, that to my mind confirms this books’s true quality; further exploration uncovers a hard-bitten and often knotty core, which has much to do with its far from dreamy setting, in a timeless fishing community where both men and women work gnarled fingers to their doubtless hardily constructed bones.

The very first words of the title – and opening – poem conjure up a finger-clicking transformation suggestive of magic, perhaps even witchcraft:

“Old lass”, ostensibly a term of colloquial endearment, is in reality a deft oxymoron underpinning the key theme of transience at its most scarily swift. The skilful personalisation introducing the speaker’s mother emphasises rapidity of another sort – the way the imagination can splice stories, characters, whole worlds, time-zones, modes of perception together in less than an eye-blink. In the next line the journey backwards takes on a lexical aspect: “….dragging me through the plothery snicket”. As if to reinforce the significance of speed, Readman has said in an interview that these dialect words from her childhood came to her very quickly while writing the poem, even though she hadn’t thought about them in decades. Men then make what turns out to be a typically brief and largely functional, horny-handed appearance –

Fishermen knocked, bags of whelks at the door, trout like rainbows dandled in raw hands –with that second line encapsulating the dual presence of the ephemeral and the almost painfuly concrete, before the camera turns back to its main point of focus. In other poems a woman’s apparent lack of control over her own identity may seem a weakness – ‘The Morning of La Llorona’, for example, memorably ends “And I rushed to your house, a waterfall, ready / to pour whoever I thought I was into your arms.” But in ‘The Book of Tides’ the matriarchically primed woman’s particular take on ‘not knowing her own strength’ links her power with its own unknown-ness. The Lawrentian use of “inchoate” comes to mind here, as do various episodes from the Odyssey:

In ‘Radiography’, a similar sense of unsureness paradoxically gives a wide-eyed acuity and luminosity of perception to the results of an X-ray on the speaker’s mother:

Readman’s stance, if that word can be used in relation to an authorial overview of such deliberate fluidity, is feminist in the broadest and most unpresumptuous sense, in that it does not seek to downgrade a woman’s right to choose a traditionally domestic way of life. The steadfast wife in ‘The Woman Who Could Not Say Love’ expresses her love through darning holes in her fisherman husband’s clothes: “Let a stitch / in a frayed pocket proclaim / what thinking of him is.” The poet’s bravely unmodish attitude goes hand in hand with a willingness to accept without judgment, even to celebrate, what might be looked on as “old wives’ tales”. In the case of ‘The Sound of a Knot Being Untied’, this becomes old husbands’ tales, at least if one interprets the poem’s footnote literally: “Fishermen once held the superstition that some women could prevent storms by tying knots in a handkerchief, such handkerchiefs were carried for safe voyage.”

The poem itself is rather more about the recurring theme of watery transience, and stitching time rather than cloth. Once again the key idea is couched in hedging terms, modality and surmise rather than the pretence of fact, and once again we see the characteristic combination of fragile and transient (“raindrops”) with solid and grounded (“anchored a collarbone”):

You may wonder when being naked stopped being as simple as catching a woman bathe – raindrops hung on the line as water rolled, anchored a collarbone to a pulse.That anchor is of course a crucial metaphor, but in effect it’s a signifier without a signified: the fisherman’s one dependable protection against the power of water finds no analogue when it comes to time. However, there is a positive, if ambivalent slant. Having begun “Look to your lasses, lads, if you can”, the poem ends with an exhortation that both admits the unstoppable march of time and reminds us of the few but real consolations in this swiftly-passing life, with “if” transmuted, by the magic of optimism, to “while”, even as the patriarchal illusion of permanent sexual/contractual possession evaporates with “your” becoming “that”: “Look to that lass, now, / open a mouthful of sorrys, kiss her while you can.” The feminist angle here is all the more articulate for being so obliquely noted.

Other delights include the way Readman, however sophisticated in other areas, does not eschew some of the more basic tools in the poet’s armoury, particularly internal rhyme, assonance and alliteration, in which the book abounds. All of the above emerge in this quasi-Hopkinsian snippet from ‘The Morning of La Llorona’: “I killed / a kingfisher, sliced light off its back to fill gaps”. Among the countless alliterative instances, she has a true penchant for sibilance, as in the prose poem ‘Featherweight’ – “Boys who got too close snapped, spines skinny rushes whistling in the wind” – and ‘The House that Wanted to be a Boat’, which focusses on a cliffside cottage slipping into the sea through coastal erosion:

This sense of resistance (“slowly” here implies “defiantly”) even in the face of unstoppable forces is for me the collection’s keynote, one captured perfectly in the poem which moved me most of all, ‘To Kill a Robin’, where another fishing superstition – “If you kill a robin on New Year’s Day, / give a feather to a rodman and he’ll always sail clear” – leads the poem’s speaker, or rather herself as a child, to apply the dictum in earnest, only to find the supposedly powerless victim resisting her to the last. Significantly, while we are given flashes of undreamlike physicality (“the hunch of me / hunkered”, “nithered fingers”, “cave of my grasp”), water, that eternal symbol of evanescence, finds its way into the final line, just as it seeps into almost every page of this haunting and splendidly judged collection:

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, Nick Cooke, poetry