Fiona Moore applauds Cristina Viti’s fine translation of Gezim Hajdari’s poems of exile

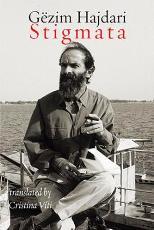

Stigmata

Gëzim Hajdari

Translated by Cristina Viti; bilingual Italian/English edition

Shearsman, 2016

ISBN 978-1-84861-441-3

142pp. £9.95

Stigmata

Gëzim Hajdari

Translated by Cristina Viti; bilingual Italian/English edition

Shearsman, 2016

ISBN 978-1-84861-441-3

142pp. £9.95

Here is an exile, writing about the existential condition of exile and loneliness. He had to leave his native Albania for political reasons: Gëzim Hajdari has lived in Italy for over 20 years. Though he speaks of the fear / of dying in a foreign language (p18), Hajdari writes his poems in both languages and Stigmata was first published in a bilingual Albanian/Italian edition in 2003, long before the current crisis in the Mediterranean. His translator from the Italian, Cristina Viti, is an Italian poet and translator living in London.

These poems are declaratory, incantatory. They are full of statements about the unhappiness and longing of exile; about suffering, as the book’s title indicates. They are also full of striking imagery, much of it elemental and natural, that helps to give a largeness of scale. Each poem is headed by a single asterisk not a title and there are no divisions in the book; many poems come across as multiple versions of or variations on the same thought. Stigmata could be described as a thought sequence.

When quoting I’ll give the page number and put the English translation first and then, in most cases, the Italian for those who would like to follow it. The book’s opening poem (p10) is a good introduction to what’s to come. It ends:

Standing in line next to cold weather next to destiny

I wait to be called at daybreak from the stones

by wan faces of hoarsened voices.

My name a line separating

darkness from light,

my body a border between sand and sky.

*

In fila accanto al freddo e al destino

attendo che mi chiamino all’alba dalle pietre

volti pallidi di voci arrochite.

Il mio nome linea che separa

la luce dall’oscurità,

il mio corpo limite tra la sabbia e il cielo.

The voice and tone of this poem are sustained through the book. The persona that Hajdari sets up – the unhappy, lonely exile longing for lost country and lost love – can seem intensely personal while remaining impersonal and universal. Form is similar throughout, cogent syntax and free verse whose line breaks mostly go with the sense, and the melodious assonance that comes easily with Italian.

The imagery’s what I find compelling. From p74:

I belong to a people

blinded sevenfold by stones

and I’m no longer able to dream

under the same locked sky

of which I was a memory.

Appartengo ad un popolo

accecato sette volte dalle pietre

e non riesco più a sognare

sotto lo stesso cielo chiuso,

di cui ero memoria.

In that passage there’s the inversion in the idea of the sky remembering the absent person, the stone-blindness denoting Hajdari’s harsh, fierce Albanian background, and the combined claustrophobia of blindness and locked sky.

I can’t discern an overall structure to these 130 pages of poems though many are tactically well placed. I’m not sure that this matters but it does suggest the book may be best treated as a set of meditations to be dipped into, the poems read a few at a time so that each can be fully enjoyed for its imagery and thought. Those of us who tend to get through lots of poems quickly on first reading a collection may find that the poems blend into each other and the plangency becomes overwhelming for contemporary tastes.

There are a few political poems scattered through Stigmata which bring a change in tone: acerbic, polemical. The back cover blurb explains that Hajdari was politically active in the early 1990’s as Albania underwent the difficult transition to democracy. He spoke out then against both past crimes of the communist Hoxha regime and present ones of the post-communist government; he was repeatedly threatened and had to leave. Like so many exiles he’s neither at home in his adopted land nor in sympathy with the mood of his home country (p88):

How they have left you, Land of Dawn,

shit & piss

your poets

swearing oaths in the name of the Flag!

*

Come ti hanno lasciato paese dell’alba,

merda i piscia

i tuoi poeti

che giurano in nome della Bandiera!

I wish I could assess the Albanian literary and cultural inheritance of Hajdari’s poems. In her translator’s note Cristina Viti says: “Born in an Albanian mountain village from a family who had strong connections with the Bektashi Sufis, he still carries in his memory not only the songs and stories of his homeland’s lore, but many verses of the Kanun, the oral code of law and honour rooted in the sacredness of the word (besa) that he was taught as a child”. As for his Italian background I’ll only venture to say that he seems to take more from the early 20th century greats of Italian poetry – Umberto Saba, for example – than from later.

Viti’s translation is plain in the best sense: straightforward and true to the original. She conveys Hajdari’s plangency. Italian is supposed to be hard to translate but there is no sense of difficulty here. The English has that slight otherness that translations sometimes have, which feels exactly right. This is the beginning of one (p68) of the many poems that address an absent love who’s sometimes hard to distinguish from the absent motherland:

In which season do I look for you,

from which stone do I call out to you,

on which snow do you walk.

*

In quale stagione ti cerco,

da quale pietra ti chiamo,

su quale neve cammini.

A poem about the many jobs he’s done (p20) lays out Hajdari’s experience both in Albania and in exile:

1 year a labourer in a marshland drainage company,

2 years a soldier with former convicts,

3 years an accountant in the farming industry,

3 years a labourer and field guard

on a tomato farm.

I would have enjoyed more poems like this one with its both grim and humorous take on the hard practicalities of life. Most of Hajdari’s poems in Stigmata express the thoughts, visions and longings of the lone exile but occasionally he shifts focus to describe the actual world of the displaced (p98):

For you men of Europe who scrape by each day,

for you women of the East who scrub floors or walk

the old people of the West around the block for fresh air,

for you immigrants who sleep on benches and wake up

immeasurably homesick,

…

for you who are alone and fugitive like me

I write these verses in Italian

and torment myself in Albanian.

*

Per voi uomini d’Europa che vi arrangiate ogni giorno,

per voi donne dell’Est che lavate per terra o accompagnate

a prendere aria i vecchi dell’Occidente,

per voi immigrati che dormite sulle panchine e vi svegliate

con un’immensa nostalgia,

…

per voi che siete soli e fuggite come me

scrivo questi versi in italiano

e mi tormento in albanese.

Shearsman deserve credit for bringing Hajdari’s poems to English speakers – and allowing us the Italian too – at a time when the difficulties and danger of flight and exile, and the varied reactions to refugees in host countries, form such a powerful narrative in Europe and round the Mediterranean.

.

Fiona Moore’s second pamphlet Night Letter was published by HappenStance in 2015. She is assistant editor at The Rialto and blogs at Displacement. http://displacement-poetry.blogspot.co.uk/

http://www.happenstancepress.org/index.php/shop/product/47741-night-letter-fiona-oore

Fiona Moore applauds Cristina Viti’s fine translation of Gezim Hajdari’s poems of exile

Here is an exile, writing about the existential condition of exile and loneliness. He had to leave his native Albania for political reasons: Gëzim Hajdari has lived in Italy for over 20 years. Though he speaks of the fear / of dying in a foreign language (p18), Hajdari writes his poems in both languages and Stigmata was first published in a bilingual Albanian/Italian edition in 2003, long before the current crisis in the Mediterranean. His translator from the Italian, Cristina Viti, is an Italian poet and translator living in London.

These poems are declaratory, incantatory. They are full of statements about the unhappiness and longing of exile; about suffering, as the book’s title indicates. They are also full of striking imagery, much of it elemental and natural, that helps to give a largeness of scale. Each poem is headed by a single asterisk not a title and there are no divisions in the book; many poems come across as multiple versions of or variations on the same thought. Stigmata could be described as a thought sequence.

When quoting I’ll give the page number and put the English translation first and then, in most cases, the Italian for those who would like to follow it. The book’s opening poem (p10) is a good introduction to what’s to come. It ends:

The voice and tone of this poem are sustained through the book. The persona that Hajdari sets up – the unhappy, lonely exile longing for lost country and lost love – can seem intensely personal while remaining impersonal and universal. Form is similar throughout, cogent syntax and free verse whose line breaks mostly go with the sense, and the melodious assonance that comes easily with Italian.

The imagery’s what I find compelling. From p74:

In that passage there’s the inversion in the idea of the sky remembering the absent person, the stone-blindness denoting Hajdari’s harsh, fierce Albanian background, and the combined claustrophobia of blindness and locked sky.

I can’t discern an overall structure to these 130 pages of poems though many are tactically well placed. I’m not sure that this matters but it does suggest the book may be best treated as a set of meditations to be dipped into, the poems read a few at a time so that each can be fully enjoyed for its imagery and thought. Those of us who tend to get through lots of poems quickly on first reading a collection may find that the poems blend into each other and the plangency becomes overwhelming for contemporary tastes.

There are a few political poems scattered through Stigmata which bring a change in tone: acerbic, polemical. The back cover blurb explains that Hajdari was politically active in the early 1990’s as Albania underwent the difficult transition to democracy. He spoke out then against both past crimes of the communist Hoxha regime and present ones of the post-communist government; he was repeatedly threatened and had to leave. Like so many exiles he’s neither at home in his adopted land nor in sympathy with the mood of his home country (p88):

I wish I could assess the Albanian literary and cultural inheritance of Hajdari’s poems. In her translator’s note Cristina Viti says: “Born in an Albanian mountain village from a family who had strong connections with the Bektashi Sufis, he still carries in his memory not only the songs and stories of his homeland’s lore, but many verses of the Kanun, the oral code of law and honour rooted in the sacredness of the word (besa) that he was taught as a child”. As for his Italian background I’ll only venture to say that he seems to take more from the early 20th century greats of Italian poetry – Umberto Saba, for example – than from later.

Viti’s translation is plain in the best sense: straightforward and true to the original. She conveys Hajdari’s plangency. Italian is supposed to be hard to translate but there is no sense of difficulty here. The English has that slight otherness that translations sometimes have, which feels exactly right. This is the beginning of one (p68) of the many poems that address an absent love who’s sometimes hard to distinguish from the absent motherland:

A poem about the many jobs he’s done (p20) lays out Hajdari’s experience both in Albania and in exile:

I would have enjoyed more poems like this one with its both grim and humorous take on the hard practicalities of life. Most of Hajdari’s poems in Stigmata express the thoughts, visions and longings of the lone exile but occasionally he shifts focus to describe the actual world of the displaced (p98):

Shearsman deserve credit for bringing Hajdari’s poems to English speakers – and allowing us the Italian too – at a time when the difficulties and danger of flight and exile, and the varied reactions to refugees in host countries, form such a powerful narrative in Europe and round the Mediterranean.

.

Fiona Moore’s second pamphlet Night Letter was published by HappenStance in 2015. She is assistant editor at The Rialto and blogs at Displacement. http://displacement-poetry.blogspot.co.uk/

http://www.happenstancepress.org/index.php/shop/product/47741-night-letter-fiona-oore

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, Fiona Moore, poetry