Richie McCaffery gives a largely enthusiastic welcome to collection of critical essays by Katy Evans-Bush

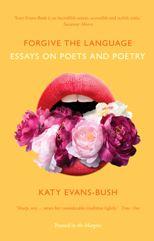

Forgive the Language: Essays on Poets and Poetry

Katy Evans-Bush

Penned in the Margins

ISBN 9781908058324

230 pp £10.99

Forgive the Language: Essays on Poets and Poetry

Katy Evans-Bush

Penned in the Margins

ISBN 9781908058324

230 pp £10.99

It is rare to see single-author, collected volumes of essays and criticism these days which is strange considering that so much poetry is being published. While there is still a culture of written criticism surrounding poetry, much of it has become tepid and rather anodyne. This is why it is good to come across such as book as Forgive the Language, which, while being unfalteringly contemporary, also harks back to an era of more intellectually testing, and testy, literary criticism where figures like Ian Hamilton of The New Review (mentioned a few times in this collection), could build a reputation on the basis of both their own poetry and their rather hard-line critical writings. This is not to compare Evans-Bush with a reviewing Momus like Hamilton, but I was pleased to see how these essays move between approbation and disapproval, hobby-horse pieces and jeux d’esprit (such as a fascinating paean to typewriters) and stronger manifestos, such as ‘The Line’ which is a call to arms for poets to not let their control of ‘the line’ in poetry slip through to literary sleuthing on plagiarism in contemporary poetry.

The pieces on offer here range between fairly straight-up literary reviews of poetry collections, and longer articles often on the theme of poetic rehabilitation or resurrection of neglected poets, such as the long-forgotten WW1 poet Eloise Robinson. That said, as a firm admirer of James Merrill’s work, I was surprised by the tone taken in the opening of an article on his admittedly neglected work where if you mention James Merrill in the UK […] you will quite probably draw a blank face. I am not sure this is an entirely fair reflection of the knowledge of most widely read UK poetry readers. The once overlooked but now increasingly fashionable Louis MacNeice is given an excellent hearing for his masterwork Autumn Journal in a long and engaging article on his work. Here Evans-Bush invests her criticism and analysis with a personal story (something which always hooks the reader) about her renewed engagement with Autumn Journal which Evans-Bush read while preparing for risky eye-surgery. Thus the whole article is framed within a personal, biographical context which is entirely winning, embedding an authorial narrative within MacNeice’s own wartime story.

For me, the outstanding essay here is ‘By the Light of the Silvery Moon: Dowson, Schoenberg and the Birth of Modernism’ which not only salvages my own favourite fin de siécle poet by far, Ernest Dowson, from relative neglect (Evans-Bush even talks about the neglect then refurbishment of Dowson’s grave) but argues that the high meridian of his decadent verses allowed ultra-modernist composer Schoenberg the template of a fellow artist who died thinking he was misunderstood and a failure. The piece offers a fascinating glimpse into the 1890s-1910s that reminds me somewhat of the enthusiastic writings of learned ‘bookmen’ like AJA Symons and John Gawsworth, but brought bang up to date. I would say that the article neglects to mention an important poet who, to me, seems to link the rather thanatic, ethereal beauty of the decadents with the game-changing modernists – the Scottish writer John Davidson (d. 1909) who straddled and enriched both worlds. But that said, this essay alone made the collection a worthwhile read for me.

I found myself very largely in sympathy with Evans-Bush’s assessments, assertions and judgments throughout but I would say that the book leans too heavily on the critical writings of Don Paterson, who is mentioned in nearly half of these articles and who almost becomes a prop. Apart from that, the collection is, in my eyes, only held back by some rather poor proof-reading. Take for example the excellent sequence of reviews of the late Irish poet Dorothy Molloy (1942-2004) where the dates of her life, and death, are repeatedly mentioned and never tally. We are told at first she was nearly 64 when she died, then we are told her first book was published shortly after she died in January 2003 and then we are finally told she died aged 61 from cancer. While this might sound like hair-splitting, it does undermine the authority of the critical writing. Similarly, in ‘Beauty and Meaning: Free the Word!’, which is an article on concrete poetry, there seems to an issue with Ian Hamilton Finlay. He is first called ‘Ian Finley (sic) Hamilton’ and then we are told about ‘Ian Hamilton Finlay, whose magazine Poor. Old. Tired. Horse was a leading vehicle of concrete poetry in the UK in the 50s and 60s’ (Hamilton Finlay’s magazine ran from 1962-1968). Again, this is pettifoggery, but the mistakes do trip you up. These are tiny quibbles in an otherwise very welcome, engaging and highly percipient collection that pays no attention to trends and is unafraid to champion the overlooked or neglected with often very fruitful results that will appeal to the scholar and casual reader alike.

Richie McCaffery gives a largely enthusiastic welcome to collection of critical essays by Katy Evans-Bush

It is rare to see single-author, collected volumes of essays and criticism these days which is strange considering that so much poetry is being published. While there is still a culture of written criticism surrounding poetry, much of it has become tepid and rather anodyne. This is why it is good to come across such as book as Forgive the Language, which, while being unfalteringly contemporary, also harks back to an era of more intellectually testing, and testy, literary criticism where figures like Ian Hamilton of The New Review (mentioned a few times in this collection), could build a reputation on the basis of both their own poetry and their rather hard-line critical writings. This is not to compare Evans-Bush with a reviewing Momus like Hamilton, but I was pleased to see how these essays move between approbation and disapproval, hobby-horse pieces and jeux d’esprit (such as a fascinating paean to typewriters) and stronger manifestos, such as ‘The Line’ which is a call to arms for poets to not let their control of ‘the line’ in poetry slip through to literary sleuthing on plagiarism in contemporary poetry.

The pieces on offer here range between fairly straight-up literary reviews of poetry collections, and longer articles often on the theme of poetic rehabilitation or resurrection of neglected poets, such as the long-forgotten WW1 poet Eloise Robinson. That said, as a firm admirer of James Merrill’s work, I was surprised by the tone taken in the opening of an article on his admittedly neglected work where if you mention James Merrill in the UK […] you will quite probably draw a blank face. I am not sure this is an entirely fair reflection of the knowledge of most widely read UK poetry readers. The once overlooked but now increasingly fashionable Louis MacNeice is given an excellent hearing for his masterwork Autumn Journal in a long and engaging article on his work. Here Evans-Bush invests her criticism and analysis with a personal story (something which always hooks the reader) about her renewed engagement with Autumn Journal which Evans-Bush read while preparing for risky eye-surgery. Thus the whole article is framed within a personal, biographical context which is entirely winning, embedding an authorial narrative within MacNeice’s own wartime story.

For me, the outstanding essay here is ‘By the Light of the Silvery Moon: Dowson, Schoenberg and the Birth of Modernism’ which not only salvages my own favourite fin de siécle poet by far, Ernest Dowson, from relative neglect (Evans-Bush even talks about the neglect then refurbishment of Dowson’s grave) but argues that the high meridian of his decadent verses allowed ultra-modernist composer Schoenberg the template of a fellow artist who died thinking he was misunderstood and a failure. The piece offers a fascinating glimpse into the 1890s-1910s that reminds me somewhat of the enthusiastic writings of learned ‘bookmen’ like AJA Symons and John Gawsworth, but brought bang up to date. I would say that the article neglects to mention an important poet who, to me, seems to link the rather thanatic, ethereal beauty of the decadents with the game-changing modernists – the Scottish writer John Davidson (d. 1909) who straddled and enriched both worlds. But that said, this essay alone made the collection a worthwhile read for me.

I found myself very largely in sympathy with Evans-Bush’s assessments, assertions and judgments throughout but I would say that the book leans too heavily on the critical writings of Don Paterson, who is mentioned in nearly half of these articles and who almost becomes a prop. Apart from that, the collection is, in my eyes, only held back by some rather poor proof-reading. Take for example the excellent sequence of reviews of the late Irish poet Dorothy Molloy (1942-2004) where the dates of her life, and death, are repeatedly mentioned and never tally. We are told at first she was nearly 64 when she died, then we are told her first book was published shortly after she died in January 2003 and then we are finally told she died aged 61 from cancer. While this might sound like hair-splitting, it does undermine the authority of the critical writing. Similarly, in ‘Beauty and Meaning: Free the Word!’, which is an article on concrete poetry, there seems to an issue with Ian Hamilton Finlay. He is first called ‘Ian Finley (sic) Hamilton’ and then we are told about ‘Ian Hamilton Finlay, whose magazine Poor. Old. Tired. Horse was a leading vehicle of concrete poetry in the UK in the 50s and 60s’ (Hamilton Finlay’s magazine ran from 1962-1968). Again, this is pettifoggery, but the mistakes do trip you up. These are tiny quibbles in an otherwise very welcome, engaging and highly percipient collection that pays no attention to trends and is unafraid to champion the overlooked or neglected with often very fruitful results that will appeal to the scholar and casual reader alike.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • authors, books, poetry, year 2016 0 • Tags: authors, books, poetry, Richie McCaffery