Caroline Maldonado finds there are many possible ways of reading this chapbook of poems by Susan Wicks with artwork by Elizabeth Clayman

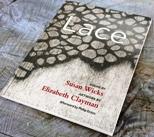

Lace

Poems by Susan Wicks artwork by Elizabeth Clayman

Stonewood Press 2015

ISBN: 978-1-910413-10-4

20pp £6.99

Lace

Poems by Susan Wicks artwork by Elizabeth Clayman

Stonewood Press 2015

ISBN: 978-1-910413-10-4

20pp £6.99

Susan Wicks is a highly respected and inventive translator of poetry as well as a poet in her own right and her collaboration with Valérie Rouzeau has recently resulted in their collection ‘Talking Vrouz’ being shortlisted for the Popescu Poetry Translation Prize. ‘Lace’ can be seen as another form of translation and collaboration. This beautiful book is made up of 13 poems in response to artwork by Elizabeth Clayman, taken from a series of 50 charcoal drawings on gessoed wood panels, which are in turn a response to antique lace from a ‘hidden’ collection in Tunbridge Wells Museum and Art Gallery. Lace-making has traditionally been women’s work: labour-intensive, fragile, often lonely, and the original commission from the museum was specifically for women writers and artists. The lace remnants are torn and decaying. The drawings are delicate in shades of black and grey; there are dark outlines, spindly threads, with varying depths of shade in the spaces between them. Their abstract forms sometimes suggest netting, fences, enclosures and, other times, gaps are opened up. Drawings and poems face one another. The poems are short, written in both free verse and more formal rhymed stanzas, and they mirror the drawings in their delicacy and precision where the lace is not only described but felt. The visual impact of the book also leaves space for the reader to develop their own associations and the result is a multi-layered and satisfying experience.

In their brief introduction Wicks and Clayman refer to the poems as ‘meditations’ and as a journey in which the ‘she’ surfaces. They also invite a reading as a study of and eventual escape from depression. The first drawing of lace looks like a sprawling wire fence and the second verse of the first poem indicates the start of the journey:

This lace she's knitted up

is strained and snagged, full of pulled snitches,

a soft hive of space

where the paler grey of morning

trickles in. All she can do now is go on -

take up two grey needles

listen to their clicking conversation

one against the other, mending this dark tatter

knitting it better.

The alliteration in the second line and the repeated ‘i’ sound in knitted/snitches /trickles/clicking /knitting echoing the needles suggests the dull repetitive nature of a depressed state of mind, but morning light is trickling into the verse and torn remnants can be mended.

The fourth poem is a cry of pain and the lace is the body:

And what price truth?

Oh, let my body go. Let there

be numbness, paralysis.

The pain flows upwards, spreads its capillaries

as delicate as cobwebs, grey as antique lace

inside the bone.

The sixth poem faces a drawing with dark netted strands falling vertically round an oval space:

Here is a woman's body, turning white

fattening like a slug. Each morning it bleeds

a juice like sap, its head is full of light.

It cuts itself and what flows out is milk.

These poems can be read as a journey out of depression or as a revelation of the hidden aspects of women’s lives or as an elegy to things we discard, but a reductive reading would lose all the other possible associations which this ‘meditation’ leaves open for us.

Caroline Maldonado finds there are many possible ways of reading this chapbook of poems by Susan Wicks with artwork by Elizabeth Clayman

Susan Wicks is a highly respected and inventive translator of poetry as well as a poet in her own right and her collaboration with Valérie Rouzeau has recently resulted in their collection ‘Talking Vrouz’ being shortlisted for the Popescu Poetry Translation Prize. ‘Lace’ can be seen as another form of translation and collaboration. This beautiful book is made up of 13 poems in response to artwork by Elizabeth Clayman, taken from a series of 50 charcoal drawings on gessoed wood panels, which are in turn a response to antique lace from a ‘hidden’ collection in Tunbridge Wells Museum and Art Gallery. Lace-making has traditionally been women’s work: labour-intensive, fragile, often lonely, and the original commission from the museum was specifically for women writers and artists. The lace remnants are torn and decaying. The drawings are delicate in shades of black and grey; there are dark outlines, spindly threads, with varying depths of shade in the spaces between them. Their abstract forms sometimes suggest netting, fences, enclosures and, other times, gaps are opened up. Drawings and poems face one another. The poems are short, written in both free verse and more formal rhymed stanzas, and they mirror the drawings in their delicacy and precision where the lace is not only described but felt. The visual impact of the book also leaves space for the reader to develop their own associations and the result is a multi-layered and satisfying experience.

In their brief introduction Wicks and Clayman refer to the poems as ‘meditations’ and as a journey in which the ‘she’ surfaces. They also invite a reading as a study of and eventual escape from depression. The first drawing of lace looks like a sprawling wire fence and the second verse of the first poem indicates the start of the journey:

The alliteration in the second line and the repeated ‘i’ sound in knitted/snitches /trickles/clicking /knitting echoing the needles suggests the dull repetitive nature of a depressed state of mind, but morning light is trickling into the verse and torn remnants can be mended.

The fourth poem is a cry of pain and the lace is the body:

The sixth poem faces a drawing with dark netted strands falling vertically round an oval space:

These poems can be read as a journey out of depression or as a revelation of the hidden aspects of women’s lives or as an elegy to things we discard, but a reductive reading would lose all the other possible associations which this ‘meditation’ leaves open for us.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, books, drawing, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: art, books, poetry